Early immigrants to Victoria included highly-skilled scientists and specialists. John Cotton was one such man.

Born in London in 1801, Cotton studied law at Oxford University before going to work for a legal firm. But his interests lay elsewhere: he was passionate about birds. By the age of 33 he had published The Resident Song Birds of Great Britain (1835).

In 1843 Cotton sailed for Port Phillip with his wife Susannah, their four sons, five daughters and several female servants to embark on life as a squatter. He documented the voyage in the book of poems Journal of a Voyage in the Barque 'Parkfield' . in the Year 1843, one of the first pieces of Australian verse published.

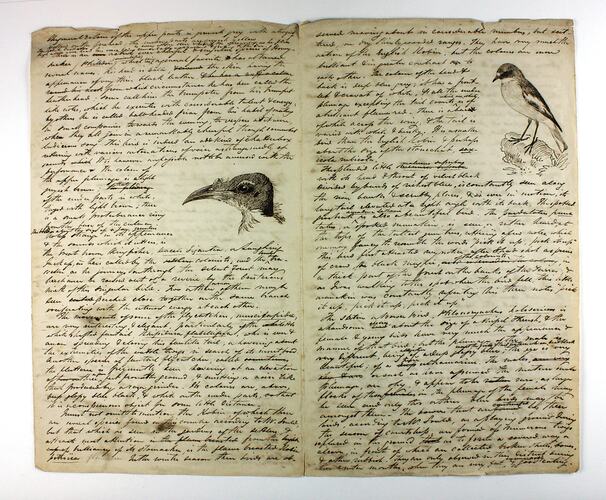

The family soon settled at 'Doogallook' on the Goulburn River, the first of several stations leased by Cotton. He quickly began to draw, paint and describe the birds around him. He shot birds for close observation - and even tasted them! He says the bronze-winged pigeon Peristera chalcoptera [Common Bronzewing Phaps chalcoptera] made 'excellent eating'. He also preserved bird skins, and hoped to supplement his income by selling them in London.

Within six years he had documented 158 bird species in pen, pencil and watercolour sketches. Due to environmental and land use changes since, many of these bird species no longer exist where Cotton observed them. In 1848 he published a list of Victorian birds in the Tasmanian Journal of Natural Science.

John Cotton had bigger plans, which he shared with his brother William 'As I have now upwards of a hundred drawings of the birds found in this district, I think that something might be made of them by bringing them before the public in the shape of a small vol'(letter to his brother William, December 1848). This was to be the first published book of Victoria's birds.

Unfortunately Cotton had little time for his ornithological work. The Cotton family first lived in a four-room slab hut and later a larger sawn timber and slab house. Conditions at 'Doogallook' were challenging, particularly since workers were in short supply. Cotton and his assistants worked throughout the day on his properties, which by 1846 carried thousands of sheep. Susannah and her daughters did most of the domestic work - a new experience for many upper-class women. Amidst this, Susannah gave birth to her tenth child.

Cotton cheerfully reported that 'My wife, who was greatly prejudiced against the bush, has become perfectly reconciled, and derives pleasure from attending to her numerous poultry and domestic affairs...[She] is able to cook our meals, and delights in showing her readiness in such employment'(letters to brother William, May 1844). We do not know how Susannah really felt as none of her writings have survived.

John Cotton's observations extended beyond birds to other species, and even to people around him. He wrote in detail about his family and friends, and was fascinated by local Indigenous people. His land sat on the edge of a floodplain where the Taungurung people traditionally gathered and lived. European settlement meant that they were displaced from their lands; however they continued to live on the fringes of the area frequenting ration stations, trading with the settlers and working for them.

Cotton seems to have been on good terms with the local people, and recorded their cultural practices such as corroborees with genuine interest. Typical of his time, he firmly believed that those who first cultivated the land - that is, squatters like him - had the right to ownership, and therefore could dispossess the original inhabitants.

It did not occur to Cotton that the bushfires which (he thought) were lit by Indigenous people to clear pathways might have actually been a means of 'turning forest land to their own use', giving them 'far better title to the soil than the Queen of England' (John Cotton's own words).

For all his achievements, John Cotton lived in Victoria for just six years. He died unexpectedly on 15 December 1849, aged 47, his book of Victorian birds still unpublished. He left behind his wife and ten children; Susannah died only three years later.

Cotton's notes and illustrations were passed down through generations of his family, until his great-granddaughter worked with author Alan McEvey to see them published 125 years later, in 1974, as John Cotton's Birds of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, 1843-1849.

His original illustrations were donated to the State Library of Victoria. Museum Victoria and his descendants hold his other writings.

References

Cotton, John 1845, Journal of a voyage in the Barque Parkfield, Captain Whiteside, from Plymouth to Port Philip [sic], Australia in the year 1843, Samuel Bentley and Co, London

Mackaness, George 1953, The correspondence of John Cotton: Victorian pioneer, 1842-1849 in three parts, G. Mackaness, Sydney

McEvey, Allan 1974, John Cotton's Birds of the Port Phillip District of New South Wales, 1843-1849, Collins, Sydney

More Information

-

Keywords

British Immigration, Immigration, Birds, Scientific Research, Indigenous Cultures

-

Authors

-

Article types