The Court's exhibits were essentially grouped by region, as a visiting journalist from the Sydney Morning Herald observed:

- those from Bengal, from Bombay, from Madras, from the Punjaub, and from the north-west provinces, and in each of these groups will be found illustrations of the manners and customs of the people, their skill in the arts and manufactures, and their natural resources and raw materials.

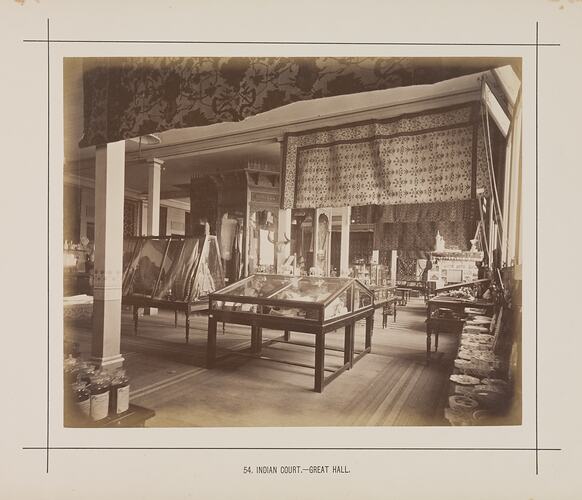

Upon entering the Indian Court, visitors were greeted by the attractively arranged displays around the walls of carpets in striking design and colour, 'disposed so harmoniously as to avoid anything like gaudiness.' Exhibition attendees could purchase a carpet costing anywhere between £10 and £80. While it was noted that such prices might seem initially high, one journalist observed that 'it would not prove so in the long run ... Carpets of this kind have been known to last, in spite of heavy and continuous wear, for over 50 and 60 years, and such is the permanency of the Indian dyes that the colour never fades, and the goods look almost as well when they are nearly worn out as they do at first.'

Ivory carvings from the country's North-West provinces depicted Hindu gods, elephants, Ganges river boats and their crew, and bullock carts. Shawls, ranging in quality from the plainest cashmere to the highest quality silk of oriental patterns; brass work of such quality that it was awarded first prize at the Melbourne Exhibition, along with Mahomed Hussein's painting on ivory which also secured a gold medal.

Much like China, tea was an important export commodity back to Europe. At the time of the International Exhibition, efforts were being made by the Tea Syndicate of India to establish a presence in Melbourne to import Indian teas into the Colony. Melbournian industrial chemist, James Cosmo Newbery, was reported to have analysed examples of Indian tea and proclaimed them superior than their Chinese counterparts. In order to encourage Melbourne's buying public to reach the same conclusion, visitors to the Indian Court were offered a fragrant cup of tea in the adjoining Indian pavilion.

The approach was successful, for by the end of the Exhibition in April 1881, it was noted that in one day in the Melbourne market, more Indian tea had been sold 'than had previously been imported in a whole year'. Indian Court exhibitors were successful in a number of categories, with a particular strength being in the fields of furniture and jewellery. Deschamps & Co of Madras won a First Order of Merit (Silver) for their 'large cabinet, in rosewood and carved sandalwood' in Jury Section XI for 'Furniture and Accessories'. Similarly awarded were the firms of Jaffer, Sulliman and Co, Bombay, and Nanda Jethi Sonar, from Bengal, that were both recognised with a First Order of Merit (Silver) for their gold and silversmith work.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types