VICTORIA LYRE BIRD (Menura Victoriae, Gould)

'Geographical Distribution - Victoria

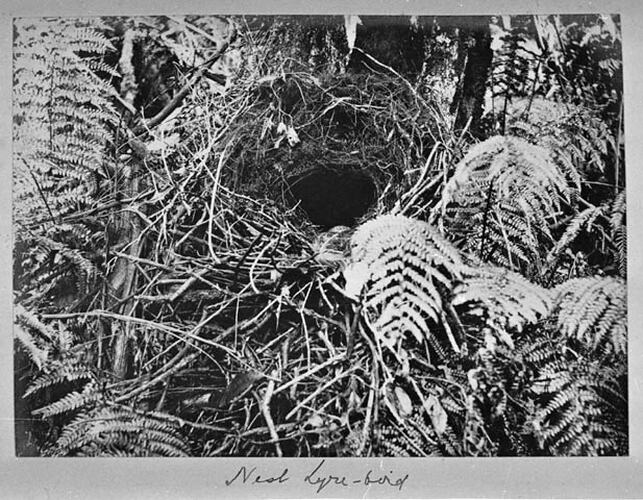

Nest - The inner or nest proper is constructed of the dark wire-like and fibrous material of fern-tree (Dicksonia) trunks and other fern rootlets, closely matted and interwoven with stringy leaves, moss, earth, &; the inside bottom being lined with the bird's own feathers. It is about twice the size and the same shape as a modern football, with an end lopped off, which serves for a rounded side entrance. This inner nest is embedded in or protected by an exterior construction composed of large sticks and twigs, which are extended at the bottom into a platform or landing-place at the entrance. Frequently over the whole structure are artfully placed a few fronds (dead or green) or other vegetation. The situations and localities, which are various, are given a length in the 'Observations'. Dimensions over all: height, breadth and length, 24 to 30 inches every way; nest proper, 15 inches long by 12 inches in depth; inside, from wall to wall or from floor to roof, 10 to 12 inches; from entrance to back wall 13 to 14 inches; entrance 6 inches across, the ragged platform or landing-place extending 5 or 6 inches beyond the entrance.

Eggs - Clutch, one only; inclined to over or an ellipse in shape; texture somewhat coarse; surface minutely pitted but glossy; colour varies from light to very dark purplish-grey, largely blotched, more or less, with dark-brown or sepia and dull purplish-slate. Sometimes the markings are of a more spotted character, and are thickest on and around the apex. When full an egg weighs 2 ¼ ounces. Dimensions in inches of selected examples: (1) 2.6 x 1.74, (2) 2.6 x 1.73, (3) 2.42 x 1.72. (Plate 16).

Observations - The chief difference between the Lyre Bird of New South Wales and the Victorian Lyre Bird is that in the latter species the rufous bars in the two outer tail feathers are more defined and broader, especially at the base, and the colour is much stronger and deeper. The darker tint is also observable in the tails of the females. Certainly these seem slender grounds (as Gould himself admitted) for separating the two species. But since the great naturalist's day, no ornithologist has been bold enough to say they are not distinct. However, it would be highly interesting to learn where the two species insulate or what tract of country divides the one kind of bird from the other.

The geographical limits of the Victorian Lyre Bird extend throughout the Australian Alps and adjacent spurs, as far westward as the Plenty Ranges and southward through favourable tracts of country to the coast.

Gould names the Victorian Lyre Bird after our Gracious Sovereign Lady, in 1862, from specimens received from the late Sir Frederick McCoy.

At the same time Gould quoted the description of the nest as well as the following interesting notes sent to him by Dr. Ludwig Becker: 'A nest and egg found on the 31st August arrived in Melbourne on the 4th September in a good state of preservation. This was somewhat astonishing, considering that the blackfellow carried them on his back day by day, wrapped up in his opossum skin (rug), while by night he had to protect them from wild cats and other animals. In Melbourne, unfortunately, or rather fortunately, the egg was broken, and an almost fully-developed young one dropped out, which would in the course of two or three days have broken through the shell.

'The young one is almost unfledged, having only here and there feathers resembling black horse-hair, of an inch in length. The middle of the head and spine are the parts most thickly covered, while the fore arm and the legs are less so. A tuft is visible on its throat and two rows of small and light-coloured feathers on its belly. The skin is yellowish-grey colour; feet dark; claws grey; beak black; eyelids closed.

'I believe that the period of incubation of the Lyre Bird begins in the first week of August, and that the young one breaks through the shell in the beginning of September.'

Dr. Becker, writing in September, 1859, stated that in October of the preceding year a nest of the Lyre Bird was found in the densely wooded ranges near the source of the River Yarra. The nest contained a young bird in a sickly state, and large in size compared with its helplessness. When taken out of the nest it screamed loudly 'tching-tching,' the notes attracting the mother bird, which came within a few paces of her young and was shot for a specimen.

Probably the oldest data recorded with regard to the Victoria Lyre Bird are those given in Samuel Sidney's 'The Colonies of Australia,' published in 1853, wherein is stated that: - 'In 1844,* Mr. Hawdon, with a party of twelve able-bodied men, including black native police, was instructed by the Government to open up a practical route for cattle from Western Port to Gippsland. It was while performing this journey that he had an opportunity of closely examining the shy and curious Lyre Bird.'

'The oldest information I possess dates back to 1847, when a relative of mine commissioned a black-fellow named McNabb (a somewhat characteristic Caledonian name for an aborigine of the long defunct Yarra Yarra tribe) to obtain some tail feathers. He was absent a few days and returned with five tails, which he procured on the Yarra side of the Dandenong Ranges, and for which he received the reward of one shilling each.'

Considering that the position of the Menura on the great list of birds is unique, and that the eyes of almost every ornithologist are directed towards this wonderful bird, not much has been written and surely much has yet to be ascertained regarding the economy of a bird that will soon become scarce on account of its particular haunts being invaded and destroyed by the march of civilisation, the enactment of laws by Governments without regard to the proper protection of peculiar native fauna (the Game Act notwithstanding, which in letter now protects the Lyre Bird all the year) and the introduction of such vermin as foxes.

I have endeavoured to add my quota to the literary knowledge of the Lyre Bird by the publication of such articles as 'In the Wilds of Gippsland - Lyre Bird Shooting' (1877, 'Notes about Lyre Birds' (read before the Field Naturalists' Club of Victoria, 1884, and afterwards reprinted in the Scientific American), and 'Lyre Bird Nesting' (1884). Here it may be deemed proper to cull and re-write the more important and interesting parts of these articles, adding there to subsequent personal observations as well as information furnished by friends and collectors favourably situated, amongst whom I may mention Messrs. D. Le Souëf, J. Gabriel, R. C. Chandler, Robert Hughes, A. W. Milligan and I. W. De Lany.

My first experiences among Lyre Birds were somewhat rough if not romantic. Towards the ends of the summers of 1875 and 1877, I visited some virgin forest country that was being thrown open for selection at Neerim, about twenty miles northward of what is now the flourishing district of Warragul, or the Brandy Creek of the old coaching days. Of course, much of the timber around Neerim must be demolished now, but as I saw it one wonders how the rich chocolate-coloured soil, however generous and watered as it is with numerous delightfully cool and clear running streams, could sustain such a wealth of giant vegetation. The reader may gather some idea of its semi-tropical growth, so to speak, if he can imagine three great forests rolled into one thus: - Firstly, thickly studded elegant fern-trees entwined with various parasitical creepers, forming fairy-like bowers carpeted with a ground scrub of innumerable ferns; secondly, trees of medium height, such as sassafras, musk, pittosporum, native hazel, blackwood and other acacias, &.; and thirdly, towering above all a great forest of gigantic eucalypts. Within, and under the triple shades of these leafy solitudes, is the true home of the wonderful Menura, commonly but erroneously called a Pheasant by the selectors.

On the occasion of the first trip the score of miles between the main Gippsland road and Neerim occupied nine hours of travelling, and was only marked by an uncertain 'blazed' track, therefore I took the opportunity of travelling up on foot with a party of selector friends, but I had to return alone. On the second trip I was again alone, and portions of the forest were on fire, the track at intervals leading by roaring and burning patches, sometimes through a blackened waste of prostrate timber still smouldering. Where trees had recently fallen, if I passed on the windward side I uncomfortably felt their feverish dying breath, and far too frequently others crashed down in the neighbourhood, bringing to my mind vivid recollections of unfortunate bushmen who had yielded up the ghost pinned to the chocolate-coloured soil by detached boughs.

However, during the two trips, and notwithstanding the extremely shy disposition of these birds, I was enabled to shoot ten males, all with fresh new tails, besides as many females as I required for my collection. Although Lyre Birds were numerous, great difficulty and much patience had to be exercised in procuring them, so terribly shy are they. You patrol leisurely up a gully or along the survey lines till you hear a bird merrily whistling on his hillock, or dancing ground, a little distance in, then you commence carefully - oh, so carefully, for one false step, an extra shuffle of the leaves, or the snapping of a twig under foot, and your prey simply disappears as if by magic - to crawl on your hands and knees, as often as not wriggling snake fashion on your stomach through ferns and scrub from stump to stump and from tree to tree. Listen! The bird stops singing as if instinctively knowing danger is approaching, whereupon you have to become like a statue, fixed to some fern root, and dare not move a muscle, no, not even if you feel a land-leech attacking your legs, or a large mosquito stinging the tip of your nose. Presently the bird commences whistling as joyously as ever. On you creep, every yard nearer, so that with the excitement your heart increases in palpitation till it throbs so loudly that you fancy the bird will hear it. All the time the close humid scrub bathes you in perspiration, while great beads stand upon your forehead, then rolling off, patter on the dried leaves beneath you. Affairs are desperate now, for at last you are within shooting distance and are peering through the ferns with uplifted gun, and finger trembling upon the trigger; but, alas, the bird possessing sharper eyes than you discovers you first, and is that very second off noiselessly and unperceived. There is no alternative left but to retrace your steps to the track, and your chagrin can be better imagined than expressed. This operation you may repeat on an average five times before you get even the slightest possible chance of shooting a bird. But I found the females easy to bag, for they frequently leapt into the trees overhead to survey me.

Mr. Kendall, when generously aiding me in reading the proofs of this work, brought under my notice a little publication, Travels with Dr. Leichhardt, by Daniel Bunce, wherein Mr. Bunce mentions that towards the end of 1839 he (Bunce), accompanied by some aborigines, made an excursion (probably the first naturalists' one) to the Dandenongs, chiefly for plants, but several 'Bullen Bullen', or Victoria Lyre Birds, were obtained. Mr. Bunce was botanist and naturalist to Dr. Leichhardt during the first portion (from Sydney to Fitzroy Downs) of the Doctor's last unfortunate expedition, and afterwards curator of the Geelong Botanic Gardens. - A.J.C.

Mr. G. H. Haydon saw the Victoria Lyre Birds (3rd May, 1844) during his journey through Gippsland, and described them in his 'Australia Felix', 1846, pp. 131-133. - E.A.P.

In addition to procuring specimens I was enabled to get glimpses of the remarkable Lyre Bird at home. Each male bird appeared to possess a little hillock or mound of earth, which it scrapes up with its immense claws, and upon which it promenades while displaying its beautiful tail by reflecting and shaking the appendage over its back within a few inches of the head, all the while making the gullies or forest ring with the most melodious whistle-like notes, interspersed with curious noises, or with mimic songs and calls of other forest birds both large and small.

The toil attending to search for Lyre Birds' nests, of all nesting outs, is the most arduous, and must be experienced to be fully realized, because, firstly, these curious birds, contrary to the general rule, nest in winter, the wettest months of our year, consequently terribly boggy and greasy tracks have to be travelled; secondly, the physical features of the country to be scoured are of the roughest and wildest description, such as Gippsland alone can produce. You have to thread your way through closely-growing hazel scrub, knee-deep in wet ground ferns, then tear through rank, rasping sword-grass, cutting your very clothes, not unfrequently nastily gashing your unprotected hands and face; next, you may be entangled in a labyrinth of wire grass, holding you at every step and hiding treacherous logs over which you equilibrium is frequently destroyed, and landing upon you side, you grunt and struggle amongst rank vegetation. To clime the opposite hill you cross on 'all fours' a wet saturated log which naturally bridges the gully. In accomplishing this awkward task, overhanging fern-trees laden with moisture dash in your face, drenching you nearly as much as if some one had thrown a pail of water over you. Notwithstanding the chilly weather, there is always an amount of warmth present in these dense forests, which, together with your wholesome exercise, you are soon perspiring, and gladly you half now and again for breathing time at the head of some lovely fern gully overshadowed by giant timber where you stand in one of the silent picturesque temples of nature.

And in Thy temple will I, bending,

The wondrous works of God adore;

This is the pow'r, O Lord, extending

O'er all the world for evermore.

I said I had shot ten male Lyre Birds. By a strange coincidence, between the years 1884 and 1894, I either found or was present at the taking of ten nests, or an average of one egg a season, an ample and sufficient reward to satisfy any working oologist.

The dates of the finding were as follow: - August 3rd, 1884, three - two fresh, one half-incubated; July 24th, 1886, one, perfectly fresh; August 12th, 1891, one, addled; October 1st , 1891, one (second egg), fresh; August 11th, 1894, two - one not fresh, one about half-incubated.

I shall give a detailed account of the first outing (August, 1884), which may perhaps prove interesting, and also illustrate the class of country and particular spots where the Victoria Lyre Bird nidifies. Having arrived at a station on the Gippsland line, I entered a coach for the mountains just as a late winter's sun was disappearing below the horizon. The team of two horses was anything but reassuring, judging from their points, which reminded one of the witty American's horse that possessed such good points that one could hand one's hat on them. However, by dint of much lashing, and the passengers occasionally dismounting, the animals were kept on their "pins" till the first change. We were then trans-shipped into a lighter conveyance drawn by one horse. By the light from the zenith of a three-quarter moon we bowled merrily through the forest, and the mountains were reached in due course.

At the coach terminus I was met by a friend, who accompanied me on foot some two miles into the range. This was the last but by no means the least enjoyable portion of my evening's journey, along a lovely moonlit mountain track, chequered by shadows of towering gum-trees, while the dense scrub on either hand sent forth aromatic fragrance which was alike refreshing and invigorating. My friend's good wife had supper waiting for us, after which we discussed the probabilities of obtaining Lyre Birds' nests on the morrow.

At length a beautiful balmy morn (for it had been a mild winter) broke, and was ushered in by the voices of many birds, the cheering pipe of the Magpie, the laughing of the Jackass, clinking notes of the Crow Shrike, with a perfect chorus from numbers of the smaller fry - Thrushes, Thickheads, Acanthizas, Wrens, &c.

After breakfast my companion and I started, suitably attired with leggings and so forth, for our mountain scramble. Up the track we scattered a few beautiful Mountain Thrushes. We ascended what I shall term the first gully, a slight indentation on the face of a steep mountain. The course was indicated by ground ferns, tree ferns, and open hazel scrub moderately studded with larger trees. When almost at this gully's source, my companion's joyous call betokened a find of more than ordinary interest. I was a little higher up the ridge. A few long downward strides soon brought me to his side, and we stood gazing upon a much coveted prize, a Menura, or Lyre Bird's nest. The nest was near a crystalline spring, and was cunningly concealed in the ferns. The back part was placed up gully, while the entrance commanded a downhill view. I roughly sketched the situation, and took dimensions both in and out of the nest, and carefully side-blew the egg, which was much darker than usual. Then, with the assistance of my companion, we removed the nest bodily from its romantic resting-place and sewed it up in a large piece of canvas. The package was no small encumbrance, being six or seven feet in circumference. My companion, who possessed broader shoulders than I, suggested he should take it down the gully and deposit it near the track, to be recovered on our return homeward.

Flushed with such early success, we hastened out steps across the face of the mountain and entered a second gully richly grown with ground ferns and with more dog or blanket wood than the previous one. I still elected to beat uphill, while my companion kept below. Good fortune favoured me this time. I dis-covered the second nest in a very similar position to the former one, but slightly smaller and more com-pact, and the egg was more beautiful and lighter in colour.

The third gully brought us to very slippery ground, and at times we had much difficulty in retaining our footing. We beat this gully to its source, and emerged on the summit of the range. Travelling along its crest for some distance we made a dip to the right into a hollow. This, the fourth gully, was not so steep, and was a somewhat boggy watercourse. It contained some beautiful ferns, notably a pretty coral-like variety (Gleichenia), which in places entwined itself up the scrub to a height of ten or twelve feet. There were also a few sassafras trees. One of the saplings I felled, to serve as an alpenstock, and a very great assistance it was in such rough country, while its wounded bark emitted a highly scented and pleasant perfume.

In the fifth gully we came across deserted prospectors' diggings. Nearly all the watercourses show specks of gold, and experts state that payable reefs may yet be discovered in the district. However, all that we found of interest in our line were two old Lyre Birds' nests. They were conjoined and placed between two fern trees. The top one was probably last year's nest, the underneath one the preceding season's.

The sixth and seventh gullies were much alike in character, indeed all the courses are thickly timbered, with as much lying on the ground as is standing. It requires great perseverance and energy to travel through such country; the greatest difficulty is clambering over huge dead trees and other decayed fallen timber, which at all times are damp and slippery, but especially at this period of the year. You never know where your next footstep will land you. For instance, when you step upon a greasy tree-barrel it is extremely doubtful whether your foot will slip up, or down, or over the side. Should you sur-mount the obstacle successfully the chances are you my bottom a crab or earth-worm hole up to your knees in mud. The country is favourable for the great earth-worms that we hear so much about, but read very little of. Their size varies from three to seven feet. They produce subterraneously a peculiar sucking noise when receding rapidly into their holes. In such country you can only afford one eye to look for nests, while the other is reserved to navigate the scrub and observe locality, because, be it remembered, there is nothing easier than to get bushed in such heavily-timbered ranges.

By this time it was late in the afternoon, and we directed our thoughts homeward. We decided to make the eighth gully the last, to beat it to its source, thence again gain the top of the range. This gully became more enchanting as we neared its spring. The banks gradually steepened on either side where, thickly studded, were noble tree-ferns, whose dark-brown trunks were overgrown with mosses, lichens and parasitical ferns innumerable, and their long graceful fronds which met overhead, quite darkened and softened the picture. With such charming glimpses of primeval nature, the sense of smell was equally satiated by the powerful and delightful aroma that floated in the air from the blossoming sassafras above.

Along this secluded sylvan arcade I proceeded slowly and carefully, feeling assured that some Lyre Bird would choose such a romantic situation for its nest. I could hear my companion crashing through the timber u-hill. As I crawled from underneath a large fallen log, I instinctively cast an eye on the right bank and my delight can be imagined when I espied the third nest backed up against a sassafras tree, with the entrance full in my face. I sent out a 'coo-ee-ee' to my companion that made the hills ring again, at the same time the unwonted noise frighted the poor bird off the nest. She gave one bound over a log and in an instant was out of sight.

After coming out of the ferns on the saddle of the range the walking was extremely rough, through thick brackens, and other obstructive scrub, not to mention sword and wire grasses; besides, the I left the birds and their nests behind, a reaction immediately set in, fatigue and hunger making themselves pain-fully obvious. I had not broken my fast for eight hours; as for my companion, he seemed to thrive amazingly on the rarefied mountain air and tobacco smoke. He appeared used to this sort of business. I reckoned with him that I could not proceed without something to eat. My spirits revived when he in-formed me there was a hut close by where we would be welcome for a meal. The sequel proved it, because the good wife, almost before she had welcomed us, placed the kettle on a roaring fire.

While we refreshed ourselves darkness supervened, and we were still two miles or more from home, with a rugged gully to be traversed. We stepped out merrily along the track on the saddle of the range and entered the gully, which was awfully dark; what little light the clouded moon gave was now completely shut out by the thick foliage. Creeping, crawling and climbing over the rocks, stumps, &c., became the order of the evening, and was a very awkward undertaking, not to say dangerous. Several times I slipped and banged up against a tree stem, which brought me up all standing. On one very greasy patch I came a regular 'cropper' on my back, and had literally to shake myself together before I could rise, and was just in time to notice, through the gloom, my partner perform a somersault into a wombat's hole. But one peep at Nature compensated for it all. Ours was the rare privilege to witness a living scene denied to thousands of our fellow-beings. An opening in the trees presented a most lovely vista. From our position we looked down the gully upon the crowns of a mass of tree-ferns. The clouds had now withdrawn from the face of the moon and, like a grand transformation scene, the flood of light streamed in, giving all the graceful frondage and other foliage a most beautiful, subdued, silvered appearance.

After recovering, with a little difficulty, the nest we had deposited in the morning near the track, and navigating the cumbersome structure through the scrub, we arrived at my friend's house in good time for a good supper, none the worse for our day's Lyre Bird nesting, the success of which exceeded our most sanguine expectations.

The Victorian Lyre Bird mates in May or June. At that time the males sing more lustily than at any other period and, like human beings, don their best frills for courting, their ombre plumage appearing very sleek, while their graceful tail feathers are at their prime.

They commence to build at once. During the peregrinations of the forester, Mr. Robert Hughes, through the Dandenongs, he took particular notice of the foundations of the nest he saw on the 1st June and, passing the spot on the 10th July, he observed that it was completed and apparently ready for the egg. A still earlier commencement of nest construction was noted in the same ranges by Messrs. R. C. Chandler and H. Kendall, and reported in the 'Victorian Naturalist,' May, 1892. They stated that on the 23rd March they found a newly started Lyre Bird's nest, the walls of which were raised by the bird at least two inches between the time of their passing in the forenoon and return some three hours later.

The earliest authenticated record I possess of an egg noticed in a nest was on the 3rd or 4th of July. The nest and contents were subsequently washed down the gully by a great flood. Taking the three first nests I found as a guide, and judging by the state of the incubation, I should say they were laid about the beginning, middle, or end of July respectively. Therefore we may infer that the nest generally is completed a week or two prior to receiving the egg, or about the beginning of July; that, as a rule, the egg is deposited during that month and that the young is hatched about the beginning of September. The young accompanies its parent till the following laying season, and is often fed by her long after the youngster is able to help itself. When grown, the young may be distinguished by its noise - resembling that of a domestic fowl's chick - and by the chestnut colouring about the face and on the throat.

At my request, Mr. I. W. De Lany endeavoured to prove the length of incubation. He had one nest under observation, but unfortunately had to shift quarters before the period was completed. The egg was deposited in the nest on the 24th August, and when it was taken on the 15th September, or twenty-two days afterwards, incubation had not advanced much. However, the following note from Mr. De Lany shows he eventually succeeded. Writing from the Omeo district, 1898, he says: -

They (Lyre Birds) have been exceptionally late in laying this season, and the male birds have hardly whistled at all. I found a nest partly built and watched it till the egg was laid on the 1st September. The young bird did not appear till the 21st October, which is fifty days. I was beginning to think that the egg was infertile, and that the old bird kept sitting on. Another nest that I found with the egg deposited a week later is not out yet (the time of writing), so the extraordinary length of time appears to be no exception.'

I can find no evidence of Lyre Birds re-constructing their old nests, as mentioned by one writer, although the birds may build near, or even upon an old home, but, in rare instances, when the egg has been robbed, another egg has been found in the same nest.

I believe both birds aid in the construction of the nest, but the female alone incubates, the male keeping entirely away from his brooding mate.

Nests are usually placed near the ground in thick scrub, in valleys or gullies, or on ridges, as well as more level country, but generally in the neighbourhood of ferns and fern-trees, usually with a good out-look in front, or down hill.

I have already given the situations of the first three out of ten nests which I found. The following, briefly stated, were the situations of the remaining seven: -

1. In a hazel gully, on right bank, picturesquely situated on a small rock, with a fair mountain streamlet passing the base of the rock. Behind the nest were ground-ferns and other vegetation, the entrance facing west (i.e. the stream).

2. In a gully, on right bank, at the base of a fern-tree and sassafras sapling, by a stream, and backed up with a thick undergrowth of wire grass, &.; entrance south-east; bird flushed.

3. On the tope of a range near the base of a giant eucalypt by a boggy stream. Entrance north, on right bank.

4. On a hill side a foot or two from the ground, at the base of a tree-fern, and backed up with ground-ferns. Entrance faced north-east, down hill; bird flushed.

5. In a somewhat open gully on the ground, well hidden with ferns, with stream at foot. On left bank, entrance south-west; bird flushed.

6. In a gully well among the hills, resting on a fallen or reclining fern-tree and between four hazels at a height of six or seven feel from the ground. About seventy yards from a stream. Entrance facing south, downhill.

7. On left bank of a very dark and narrow gully, backed up with ground ferns, and overshadowed by fern-trees; stream at foot; entrance east; bird flushed. In all these instances the egg lay buried amongst the feathers in the bottom of the nest. Only in one instance was the egg visible when I stood in front of the nest.

However, the nest is frequently built in such other places as the hollow of an old tree butt, in sassafras or musk trees, and still higher in forks of blackwood or even eucalypts. The highest Lyre Birds' nests to my knowledge were noticed by Mr. Le Souef on the family property, 'Gembrook.' One was constructed in the fork of a white gum (Eucalypt) about seventy feet from the ground. Another was built fully eighty feet above the ground, on the jagged end of the barrel of a stringybark eucalypt, about one hundred yards from the house, the top of the tree having been blown off by tempest. In both these cases the trees grew in gullies.

When the female is sitting in the nest only her head and tail tips are visible at the entrance. The tail usually appears over her back or turned on one side.

Before leaving the situations of the nest I might mention one that was found by a botanical collector. It was wedged between four tree-fern stems (Asophila) growing from the one base. The fern was after-wards grubbed and forwarded to a botanical institution in Italy. Another nest observed by a friend of mine 24th August, 1889, was built upon a high stump on Mount Feathertop, with snow upon the ground. Probably the 'record' for Lyre Bird nesting was performed by my enthusiastic friend, Mr. Joseph Gabriel and companions during four consecutive days (the three last of July and the first of August) in the season of 1893. It will be remembered it was just at the time when the Government of the day commenced to despoil the magnificent forest tracts of the Dandenongs by throwing them open as a village settlement. No small blame to Mr. Gabriel that he "cut in" for a few eggs before the birds fell to the settlers' pots.

The following is the 'record' kindly furnished to me by Mr. Gabriel: - 'First egg found in nest at foot of gum tree about thirty feel up-hill from creek. Measurement of nest 28 inches high, 24 inches broad, and 16 inches from back to front.

'Second egg (last year's) in nest foot of gum tree twenty feet from creek. A stick had fallen across the nest and flattened it. Evidently the bird could not get to her egg.

'Third egg in nest found on side of creek on a jutting mossy bank, very prettily situated.

'Fourth egg in nest at head of tributary, nicely placed on a bank. Two of us were talking here for ten minutes, disturbing the bird, which flew out, at the same time revealing her nest which we would other-wise have missed. You may guess I flew too down the bank!

'Fifth egg in nest in fork of musk tree growing in the creek; it was about ten feet from the ground.

'Sixth egg (last year's) in nest on fork of leaning fern-tree in bed of creek.

'Seventh egg is nest in bunch of grass well up the hill near Invermay house.

'Eighth egg in nest built at foot of gum tree only fourteen feet from selector's hut, or rather, I should say, the bark had been stripped off the tree to build the hut. Nest was found three weeks before the egg was laid.

'Ninth egg in nest on ground at butt of gum tree in creek.

'Tenth egg in nest placed on stump about twelve feet from ground well up-hill.

'Eleventh egg in nest in Perrin's Creek, at foot of fern-tree.

'Twelfth egg in nest in tributary or Perrin's Creek, on leaning fern-tree.

'Thirteenth egg in nest well up on side eof hill.

'Fourteenth egg in nest on leaning fern-tree, well up the head of Sassafras Gully.'

Mr. Gabriel added that the average measurements of the eggs were 2.52 x 1.66 inches. All the eggs, with the exception of the two addled ones, were either quite fresh or just turning. They were all dark-coloured specimens excepting two, which were a trifle lighter.

Exceptions prove the rule. The Lyre Bird invariably lays a single egg a season, but rare instances of doublets are known. In the course of Mr. Chandler's long experience in the wilds of Gippsland, he has found nests containing a pair of eggs, notably on the 24th July one season, when he found two nests with each a pair of precious eggs - one lot was fresh, the other slightly incubated. Mr. Chandler kindly presented me with a pair, which at a glance one could see were as like as two peas, as the saying goes, but they were slightly smaller in their dimensions then the usual average size.

Mr. Le Souëf has also found a nest containing a doublet. It was the 25th August, 1893. Both eggs were fresh, but one was slightly lighter and larger than the other. On the following day he discovered on the steep bank of a creek another nest containing one fresh egg. Passing the same nest three weeks later, he was much surprised to see a bird fly out, and on climbing to the nest he found a second egg had been laid. The egg was slightly addled and had, Mr. Le Souëf judged, been laid about a week, or shortly after his first visit. In both these interesting instances, and upon circumstantial evidence, it may be inferred that the respective birds laid two eggs, but there remains the possibility that each egg was deposited by a separate bird, especially in the first case, where the eggs I examined were different.

I have yet to record another instance of the finding in a nest a second egg after the first had been taken. It occurred on the first October, 1892, when Messrs. Le Souëf, Chandler and myself went specially to photograph an exceedingly picturesque nest. On reaching the spot, and to our astonishment, out flushed a bird which had commenced to sit on a fresh egg. From this same nest, on the 31st July, or two months previously, Mr. Chandler took the first egg.

Although not exactly pertaining to its nidification, I may conclude my observations with other remarks as to the history of now most remarkable bird.

A writer has stated that on going to roost at night the Lyre Birds "choose a secluded spot sheltered from the wind, and mostly in a low tree." My observations are the reverse of this. About dusk I have watched them, till I almost lost their form, fly sometimes more than one hundred feet up to the thick branches of some great forest patriarch. They ascend by a succession of leaps and short flights from bough to bough and from tree to tree, always surveying the position after each move. I also know for a fact that birds have been observed coming out of gullies to roost on large dead trees on the ridges, where they have been shot. In roosting they do not congregate. Sometimes during moonlight seasons a cock bird from his elevated perch agreeably disturbs the midnight stillness of the forest by his delightful whistle. Speaking about night, it is said that the Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua) occasionally takes Lyre Birds off their roost.

The powerful sonorous ring of the Lyre Bird's natural song is not surpassed by any of its Australian compeers, and, as to its mocking capabilities, it certainly would appear to leave the world's wonderful mocking birds behind. The Lyre Bird's ear is indeed so accurate that it can imitate to the very semitone the vocalism of any of its forest friends, whether the "mo-poke" nocturne of the Boo-book Owl, the coarse laughter-like notes of the Jackass or Great Kingfisher, the crack-like note of the Coach Whip Bird or the higher-pitched and more subdued notes of smaller fry. But perhaps the most extraordinary vocal performance is the imitating, not a single bird, but a flock. I have heard it imitate simultaneous sounds resembling exactly the voices of a flock of Pennant Parrakeets rising from the scrub. This clever feathered mimic is equally at home with other familiar forest sounds - the grunting of the so-called native bear (Koala), the barking of the selector's dog, the noise of the splitter's saw, or the clinking of his axe against the metal wedge - all alike are perfectly reproduced in the throat of this wonderful bird. There is a story told of a tramp who heard sawing sounds in a gully hard by. He went down to ask the supposed sawyers for matches, but found he had been duped by a Lyre Bird.

Mr. A. W. Milligan, who has recorded some facts on the imitative faculties of this 'master of ornithological song and mimicry', says the only sound the Lyre Bird cannot successfully imitate is the sound of a bell attached to a horse's neck; the jingle-jangle of the bell as the horse moves its head in the act of feeding seeming to baffle it. It may yet be proved that this bird is also an able ventriloquist.

The birds seldom or never sing in windy weather, but in South Gippsland, where the mountain spurs terminate abruptly at the sea, and where birds may be found breeding within one hundred yards of the shore, it is delightful to catch their pure liquid calls above thee boom of the ocean billows, or to hear their musical cadenzas mingle with 'the sorrowful song of the sea'.

It should be mentioned that only the cock bird whistles and mocks in this magnificent style; the hen makes but feeble attempts. I have heard her endeavour to imitate in a quiet way the notes of the Strepera and Jackass, and utter a squealing noise, especially about roosting time. Mr. Hughes has heard them making such sounds about the time the young begin to fly, as if the mother bird were teaching the youngster to use its voice.

The alarm note of both the male and the female is a short, sharp, shrill whistle, not unlike that produced by a person placing the tongue against the upper front teeth after the fashion of the street arabs. The call is a lower-pitched double note sounding like 'bleck-bleck' or 'bullan-bullan'. Both sounds, by the way, are aboriginal names for the Lyre Bird.

Mr. I. W. De Lany, who has had considerable experience among Lyre Birds in Victorian forests, has not such a good opinion of the mocking capabilities of the bird as most observer. He writes: - 'My experience as to mocking is that they do not, but every bird whistles exactly alike, and a bird during the first year, without a tail, is as perfect in his notes as the oldest. They only have the notes of a few of the birds they are amongst. If they mimicked I should think they ought to include every bird they hear. For instance, they have the voice of the Black Cockatoo, but not of the white one, nor of the Magpie, and many others I could mention that are reared in the same country with them. As to imitating chopping, sawing, cooeing, &c., it is the same as the wonderful things the old bushmen tell us about - snakes chasing them, and Jackasses all congregating in a tree to laugh at them when their dray gets stuck in the mud'.

As I have already mentioned, it is commonly known that the male bird possesses a little mound of earth, or hillock, or possibly more, which the bird scrapes up usually in the thickest of ground scrub. Upon this mound (which is about three feet in diameter) it capers and dances, also proudly drooping its wings and displaying its elegant tail, all the while pouring forth its varied songs. Between periods there comes from the throat a spasmodic buzzing or purring noise, while the tail with quivering quills is expanded or reflected over the back.

The food of the Lyre Bird consists principally of beetles, centipedes, scorpions, worms, land-crabs, and snails, and occasionally something more substantial in the shape of bush mice.

My friend Mr. R. C. Chandler tells some extraordinary bush yarns, yet I think he has not drawn the 'long-bow' in the following two instances. Twice he noticed an albino cock bird in the Bass River district. It sang most melodiously and was a lovely creature. Its pure white plumage contrasted wonderfully with the eyes, bill and legs, which were black, while the tail was large, well formed, and of the usual colour. On one occasion he witnessed two male birds fighting. Like roosters, they freely used their claws and bills, and in their excitement occasionally tripped over their tails.

It was mentioned in the 'School Paper,' Class III., May, 1896, that Mr. S. McNeilly, of Drouin, had stated he kept a pet Lyre Bird for more than eleven years. For six years the tail was like that of the hen bird. In the seventh year he got his tail complete, which grew in length until it was about 2 feet 5 inches long. This tail was shed every year.

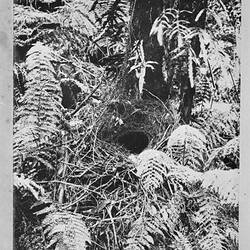

In connection with this Lyre Bird I have given three illustrations: one, 'The Haunt', depicting a typical Australian fern-tree gully; and pictures of two nests, photographed of course in situ.'

Resources

Transcribed from Archibald James Campbell. Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds, including the Geographical Distribution of the Species and Popular Observations Thereon, Pawson & Brailsford, Sheffield, England, 1900, pp. 510-523.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types