Post-Vietnam War Refugees

After the fall of Saigon in April 1975, people started fleeing from Vietnam in boats, arriving in Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia after crossing the dangerous and pirated Gulf of Thailand. Unable to bear the burden of these arrivals alone, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia managed to organise a regional response to this influx of refugees. This was known as the Orderly Departure Program. Australia, the USA and Canada (amongst others) agreed to resettle refugees, and Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia stopped resupplying or pushing off refugee boats for onward journeys. Refugee camps were set up along the west coast of Malaysia, northern Thailand and in Indonesia with the assistance of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Pulau Bidong in time became the principal refugee camp in Malaysia while Pulau Galang became the principle Indonesian refugee camp.

Australia's Response

The Australian Government set up the Australian Indo-Chinese Refugee Task Force within the then Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs to select refugees from these camps for resettlement in Australia. Lachlan Kennedy was one staff member posted to the Indo-Chinese Refugee Task Force in Malaysia from April to October 1981. The task force's operations were based in the Australian High Commission in Kuala Lumpur. Members of the task force lived in Kuala Lumpur, regularly travelling to the refugee camps in Malaysia and sometimes to Indonesia, to select people for re-settlement. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees was central to the Orderly Departure Program, but during 1981 no attempt was made by the task force to assess applicants against the criteria for refugee status in the United Nations Convention on the Status of Refugees.

Living Conditions for Taskforce Staff & Refugees

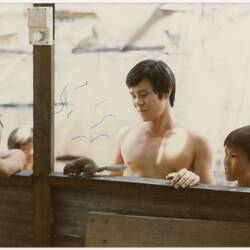

Life in Kuala Lumpur for task force members was very comfortable - air conditioned offices at the High Commission in Jalan Yap Kwan Seng, a swimming pool to which they had access seven days a week, a social club, and through the High Commission, social contact with staff at the other embassies and high commissions.

For task force officers, life in the camps was very basic, but at least the plywood sleeping quarters were rat proof - the rats tried all night to get in but never made it. Sleeping accommodation also had ceiling fans which circulated the humidity around the cabin, but the persons in the top bunks had to keep their heads down climbing in and out of their bunks. Task Force members would escape the harshness of the camp in the evenings swimming over the coral reefs or socialising on the back stairs of the hospital enjoying views of the sunset and electrical storms over the Malay Peninsula.

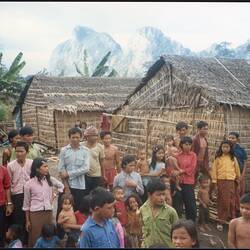

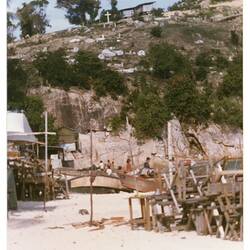

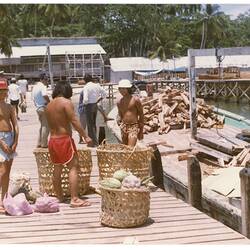

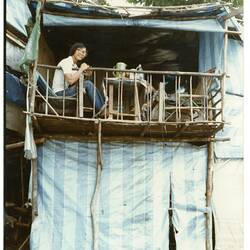

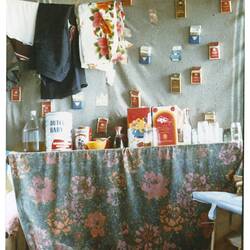

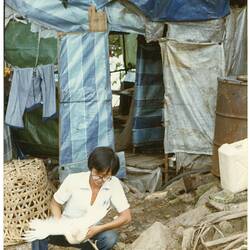

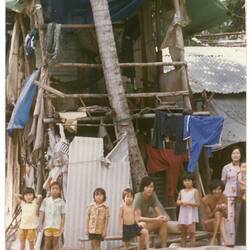

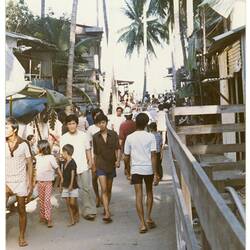

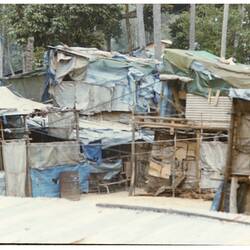

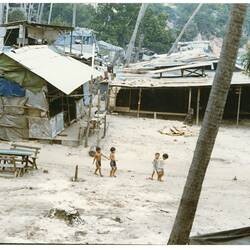

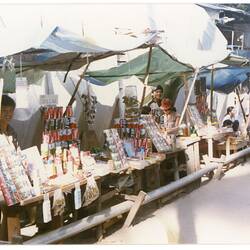

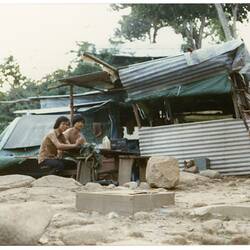

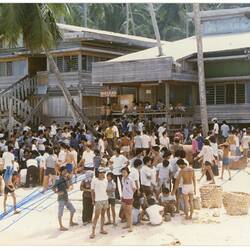

The refugees on Pulau Bidong at this time lived in wooden-framed shanty houses covered in plastic. They were breezy, which was lucky, because there was no power for cooling fans. Their houses were not rat proof. But Pulau Bidong had a library, hospital, market stalls, and two wonderful open-air cafes on the beach.

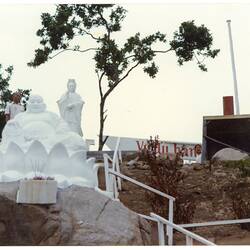

Re-Settling Refugees in Australia

Task force members knew that a person whose application for re-settlement in Australia was refused would remain on the island until their application reached the top of the interview list again and another country agreed to re-settle them.

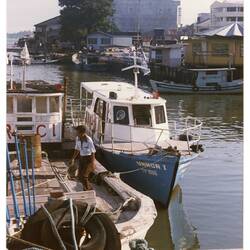

Refugees on Pulau Bidong selected for re-settlement were transferred to the Sungai Besi transit camp in Kuala Lumpur prior to travelling to their country of resettlement. Members of the task force regularly visited this camp as it was their job to supervise transport of Australian- bound refugees.

Refugees could be reasonably certain of being re-settled once they reached Sungai Besi. However, the re-settlement programs were high profile political issues in the countries of re-settlement, and therefore persons selected for re-settlement could sometimes find themselves de-selected if public opinion turned against the program. Refugees with tuberculosis found themselves particularly vulnerable to public opinion. Australian policy was to disregard tuberculosis when considering persons for resettlement, offering successful applicants treatment in the camps. This treatment involved x-rays and then a triple anti-biotic treatment under the supervision of the task force doctor that could sometimes take up to six months.

Crafting & Souveniring the Experience

Members of the task force were conscious of their small part in this historical migration program, and kept a look-out for souvenirs of their experience. The refugees had art workshops in the camps, which catered to this wide spread interest by making handcrafts. Sungai Besi had a reputation for producing quality models of Vietnamese fishing boats of the kind used by refugees to escape Vietnam.

One such boat was made by Tran Van Hoang. But tuberculosis was a near calamity for Tran. Initially selected for re-settlement in Canada, his movement from Sungai Besi camp to Canada was stopped when Canada suddenly ceased accepting refugees with a history of tuberculosis. Australia agreed to consider such cases for re-settlement and sent task force members to review their cases. On a visit to Sungai Besi, Lachlan asked the camp committee if there was a boat he could buy as a souvenir. Returning a few weeks later, he was introduced to Tran who was holding a boat he had made which he wished to give to Lachlan. Lachlan gratefully accepted it. On entering the interview room Lachlan was given the list of interviewees by the UNHCR and Tran Van Hoang was the first person on the list. Sensing the taint of corruption, Lachlan immediately returned the humble gift. The boat having been refused, it must have been a rather miserable interview for Tran. But what an unexpected surprise it must have been when he was selected for resettlement in Australia. And Lachlan was excited to be able to recover the boat on a subsequent visit.

Since Tran Van Hoang had tuberculosis he was still in the camp under the treatment when Lachlan returned to Australia at the end of his six month posting. It therefore seems likely that Tran Van Hoang was the only refugee whose boat arrived in Australia before he did.

More Information

-

Keywords

refugees, Vietnamese Immigration, Immigration Policies, Immigration Selection

-

Authors

-

Article types