Summary

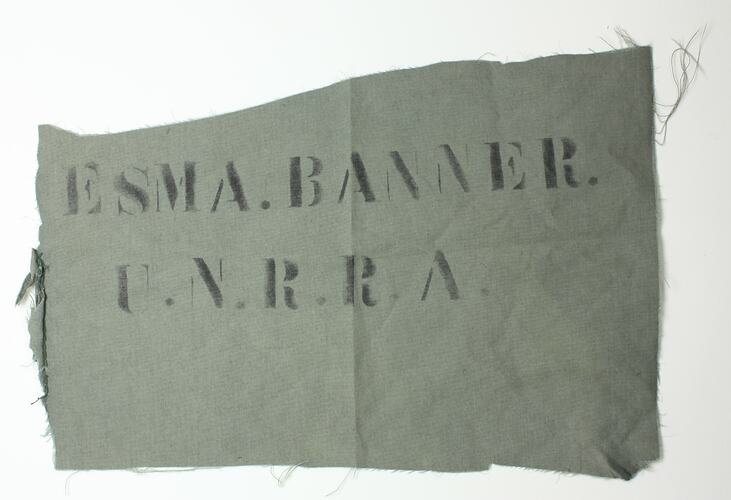

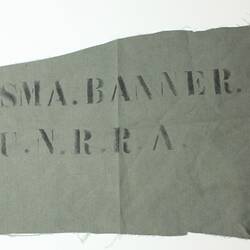

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) were established as temporary agencies to provide post-war relief care and rehabilitation as well as repatriation and resettlement of people displaced by the events of World War II.

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) were established as temporary agencies to provide post-war relief care and rehabilitation as well as repatriation and resettlement of people displaced by the events of World War II.

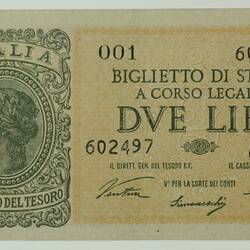

Following the Victory in Europe (VE Day) in May 1945, 6 million displaced persons remained in the Western zone of Germany, with an additional 6-7 million in the Soviet Occupied zone. In the months immediately following, an estimated 7 million people returned to their homeland, either through their own means or with the assistance of the Allied forces. However, by September 1945, approximately 1.2 million people remained in Western Germany (Cohen, 2008).

UNRRA was officially established in Washington on 9th November 1943 when 44 nations including Australia agreed to join an international organisation to provide care for those left in Germany. At the time the United Nations did not exist, and UNRRA played a landmark role in its birth (Cohen, 2008). War, disease, hunger and population upheavals were now beginning to be viewed as international problems, and thus relief work had to be equally international (Rein, 2011). The term 'displaced person' was attributed to a diverse group of people who were unwilling or unable to return to their homeland (Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Yugoslavia, Russia and the Ukraine, amongst others), as well as Soviet prisoners of war and French civilian soldiers (Slatt, 2002).

While UNRRA's ultimate objective was repatriation, within the camps relief expanded to include a number of activities that fell under the welfare title. UNRRA's mandate included providing food, clothes, health care and accommodation, as well as child welfare, occupational therapy, education, vocational training and employment opportunities (Cohen, 2008). An average centre housing 3000 displaced persons was run by a small team of UNRRA employees consisting of a director and deputy, a secretary, a supply officer, a mess officer, warehouse officer, medical officer, nurse, team cook, two welfare officers, and two drivers (Kinnear, 2004).

UNRRA was conceived as a short-term organisation to deal with an emergency, however, as the full level of displacement and destruction in Europe became evident, it was apparent that facilities would have to become more longstanding than first imagined. By 1946 Germany was also dealing with an influx of refugees who were fleeing what were then Soviet-controlled states. It was becoming clear that UNRRA's goal of complete or near complete repatriation would not be accomplished, and resettlement became the priority (Kinnear, 2004). The Preparatory Commission for the IRO (PCIRO) was formed in late December 1946, before the IRO gained full responsibilities of the camps in July 1947 (Persian, 2012 and United Nations, 1950).

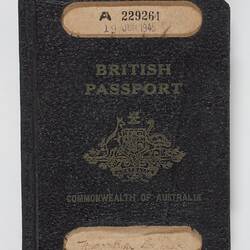

It is estimated that 600,000 displaced persons and 900,000 refugees lived in the camps when the IRO took operational responsibility (Persian, 2012). Many IRO member states including the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia were looking for migrant workers to help with post-war reconstruction, and for many people in the camps, resettlement became more preferable than returning to their homeland (Markus, 1984). The Australian Government was initially hesitant to allow resettlement of displaced persons, favouring white British migration (Markus, 1984). By 1949, after it became apparent that Britain could not provide the large number of migrant workers that the government desired, the Department of Immigration broadened Australia's immigration policy to enable 'all European races' to migrate (Markus, 1984). In total, an estimated 180,000 to 200,000 refugees were resettled in Australia under the assistance of the IRO (Persian, 2012 and Neumann, 2004).

By August 1949, it is estimated that there were about 100,000 refugees who were still dependent on the IRO's care. This relatively low number meant that the IRO formally signalled the liquidation of their operations, setting June 1950 as the date in which they would officially cease care and maintenance activities (Holborn, 1956). These individuals who remained in the camp were termed 'hard core' refugees who could not be resettled outside of Germany. Many were either elderly, ill, single mothers or had a disability, and in most instances were deemed undesirable candidates for resettlement by the IRO's member countries (McDowell, 2005).

Resources

Cohen, G. D. (2008) 'Between Relief and Politics: Refugee Humanitarianism in Occupied Germany 1945-1946', Journal of Contemporary History, 43(3): 437-449.

Kinnear, M. (2004) Woman of the World: Mary McGeachy and International Cooperation, University of Toronto: Toronto.

Neumann, K. (2004) Refuge Australia: Australia's Humanitarian Record, UNSW Press: Sydney. Markus, A. (1984) 'Labor and Immigration 1946-9: The Displaced Persons Program', Labour History, 47: 73-90.

McDowell, L. (2005) Hard Labour: the forgotten voices of Latvian migrant 'volunteer' workers, Cavendish Publishing: Portland. Persian, J (2012)

'Displaced persons and the politics of international categorisation(s)', Australian Journal of Politics, 58(4): 481-496.

Reinisch, J. (2011) 'Internationalism in Relief: The Birth (and Death) of UNRRA', Past and Present, Supp. 6: 258-289.

Slatt, V.E. (2002) 'Nowhere to go: Displaced Persons in Post-V-E-Day Germany', The Historian, 64 (2): 275-294.

United Nations (1950) Yearbook of the United Nations: 1950, Columbia University Press/United Nations: New York.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types