Chaeropus ecaudatus - Pig-footed Bandicoot (Mammalia: Peramelidae)

This species was collected during William Blandowski's Victorian government-sponsored expedition to the junction of the Murray and Darling Rivers conducted from December 1856 to December 1857, and more specifically during the eight months that the expedition was based at Mondellimin (now called Chaffey Landing at Merbein, near Mildura) from April-December 1857.

The Chaeropus was specially targeted for collection by Blandowski and the expedition naturalist Gerard Krefft. The species had been discovered some 20 years earlier by Major Thomas Mitchell during his 1836 expedition to the Murray River and southwest Victoria, however it remained poorly known. Mitchell and his Aboriginal guides Piper and the two Tommies had collected their single specimen in June 1836 near the junction of the Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers, about 130 kilometres away from Mondellimin.

At the Mondellimin camp, Krefft briefed his Aboriginal collectors before the search, using a Chaeropus illustration taken from Mitchell's expedition volumes. Despite an exhaustive hunt, the local 'Murray tribe' - the Yarree-Yarree [Nyeri-Nyeri or Latje Latje] - were unable to locate any animals on the Victorian side of the Murray River, however the first pair (a male and a female with two pouch young) was eventually brought in from the opposite side of the river, probably either by travelling Yarree-Yarree or via the 'Darling Tribe' [Barkindji] from New South Wales. The Aboriginal people called them 'Landwang', and Krefft had to trade the two animals for what he considered a very high price - 'all the money he had in his pocket, and a grand evening's entertainment with plenty of damper, sugar and tea'.

Krefft could only collect eight specimens of this rare species over the following months, all coming from the area around 'Gol Gol Creek and the Lower Darling'. He said that when Landwang were startled by the Aboriginal people and their dogs, they would take refuge in hollow logs and were easily captured alive. The Blandowski Catalogue lists the number of animals taken: nos. 1899 and 1900 (August); 2006, 2007 and 2016 (September); and 2858 and 2928 (November), plus one with no number. Krefft also collected four 'foetuses' or pouch young preserved in spirit (nos. 308, 357, 366 and 370).

Krefft obtained some additional specimens, however they never made it into the collection: 'they are very good eating, and I am sorry to confess my appetite more than once over-ruled my love for science'. Krefft did what he needed to do to survive a winter on the Murray.

The date of first collection is in some dispute. Krefft publically stated that the initial pair of specimens was collected on 4 October 1857, however this contradicts at least two of his unpublished expedition records which state that it occurred in August 1857. This was either Krefft's accidental reporting mistake, or an attempt at deception to keep the important discovery quiet until after Blandowski had left Mondellimin and returned to Melbourne in August 1857, to allow Krefft enough time by himself to keep and observe the animals alive in camp before the news of the important discovery got out.

When Blandowski finally received the news in Melbourne, he heralded the discovery in The Argus of 20 October 1857 - his field party had finally caught two live animals, and the specimens were being kept at Mondellimin. Blandowski provided a scientific name Chaeropus ecaudatus to go with the Aboriginal name. Meanwhile Krefft was busy in camp with his observations - noting among other things that the Landwang was nocturnal, 'constructs a sort of mia mia in the long grass', and usually ate grass but 'always prefers lettuces before anything else'. Blandowski never got to see any of the animals alive.

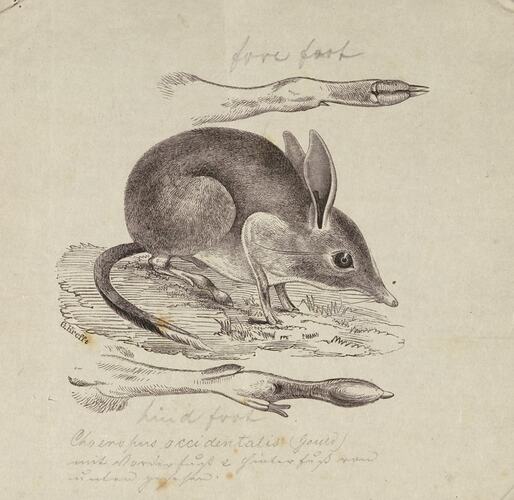

Krefft made the most of his limited time with the live specimens, producing unique descriptions and sketches. Some of Krefft's contemporary sketches have survived in international museums, and a wood engraving prepared a year or two after the expedition is held at Museum Victoria. After the death of the animals, the field team prepared skins and skeletons and carefully packed them away. Krefft eventually relinquished the collection and sent it down to Melbourne, where Blandowski at his city apartment and Public Museum director Frederick McCoy in his University of Melbourne offices were both waiting.

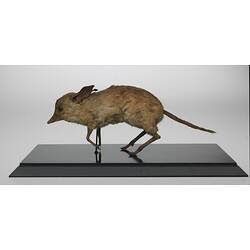

Following the break-up of the expedition in December 1857, and eventual lodgement of the collections at the museum, McCoy employed Krefft for four weeks in February 1858 to sort out the 750 mammal specimens and 29 mammal species taken in the previous year, and organise the best set of specimens to be kept for the museum and organised for display. Krefft decided to keep six of the rare Chaeropus specimens, including two skeletons and four skins (which were stuffed and mounted at the same time, with the taxidermy attributed to George Fulker, the museum taxidermist from 1854-1858).

Krefft later went on to become curator at the Australian Museum, and sought to obtain some of the rare Chaeropus specimens from McCoy for the Sydney collection. In January 1863, McCoy sent one of the stuffed male specimens from Melbourne to Sydney in exchange for the cast skull of a large Diprotodon (Krefft was building an envied collection of extinct Australian megafauna from central New South Wales). Then in August 1873, one of the Chaeropus skeletons was swapped for a specimen of the Queensland lungfish, Ceratodus forsteri (Krefft had discovered and described this species in 1870).

There are now four specimens of Chaeropus ecaudatus from Blandowski's expedition left in the Museum Victoria collection: three stuffed (registered C 27998, C 5887 and C 5889) and one skeleton (C 2900). The pouch young specimens have not been traced.

The specimens remain as important scientific evidence and a repository of information for this now-extinct species. When the specimens were collected in 1857, the species had already retreated from Victoria across the Murray River into New South Wales. A century later, by the 1950s, the species had disappeared from its last known habitat in Central Australia, and was considered extinct. The specimens are also tangible evidence of the success of the expedition, which saw European naturalists working cooperatively with Aboriginal people to build a collection and exchange information over the eight months at Mondellimin.

Further reading:

· Mitchell, T.L. 1839. Chaeropus ecaudatus (Ogilby), a new and singular animal. Plate 27, page 132 in: Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia; with Descriptions of the Recently Explored Region of Australia Felix, and of the Present Colony of New South Wales. Volume 2. T. and W. Boone: London. 2nd edition (revised).

· Blandowski, W. 1857. Chaeropus ecaudatus. The Argus, 20 Oct 1857, page 5.

· Blandowski, W. 1858. Recent discoveries in natural history on the lower Murray. Transactions of the Philosophical Institute of Victoria, from September to December 1857, inclusive, 2(2): 124-137.

· Krefft, G. 1864. Catalogue of Mammalia in the collection of the Australian Museum. Australian Museum: Sydney. 134 pages.

· Krefft, G. 1866. On the vertebrated animals of the Lower Murray and Darling: their habits, economy, and geographical distribution. Transactions of the Philosophical Society of New South Wales for 1862-1865: 1-33.

· Krefft, G. 1871. The Mammals of Australia, illustrated by Miss Harriett Scott and Mrs. Helena Forde, for the Council of Education, with a short account of all species hitherto described. Thomas Richards, Government Printer: Sydney. [34 pp.] 16 plates.

· Krefft, G. 1872. Natural history: The bandicoot tribe (continued). The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 5 October 1872, page 422.

· Wakefield, N.A. 1966. Mammals of the Blandowski expedition to North-Western Victoria, 1856-57. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria, 79(2): 371-391.

· Menkhorst, P.W. 2009. Blandowski's mammals: clues to a lost world. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria, 121(1): 61-89.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types