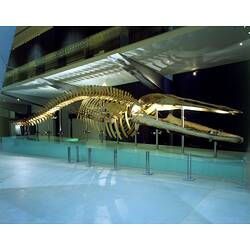

The articulated skeleton of a Blue Whale is on display at the western end of the Walk, outside the entrance to the Science and Life Gallery at Melbourne Museum.

Blue Whales, the largest animals that ever lived, are occasionally seen off the Victorian coast as they move along migratory routes feeding on krill (tiny shrimp-like creatures) as they go.

Occasionally, following a major catastrophe such as a collision with a ship, or because they are in poor health, or for other reasons that are not fully understood, Blue Whales strand or beach. Unfortunately, whales that strand on land frequently die, often from dehydration. Poor health seems to be the reason why a young male Blue Whale, 18.7 m in length, stranded and died on the beach at Cathedral Rock, near Lorne in western Victoria, in 1992.

The museum is the official place of lodgement for dead specimens of Victorian wildlife, and acquisitions of significant specimens is an important role for museum staff. If a dead whale is found stranded, the Mammalogy Department is contacted, and details of the stranding are obtained whenever possible. If the specimen has potential for research or exhibition, efforts are made by the museum to secure it.

The salvage of the Lorne whale was a massive task. Bulldozers removed the whale from the beach, and three cranes transferred it to a semitrailer. It was transported carefully to the Werribee Sewage Treatment Complex, which had a suitable work site and facilities. Photos, videos and some measurements had been taken at the stranding site, and a more detailed examination of the carcass and a post-mortem were carried out at Werribee. Although the cause of death was not established, the thin blubber, about five centimetres thick, indicated that the whale had not been feeding and was in poor condition. Tissue samples were taken for subsequent examination, particularly DNA analysis, as there are two subspecies of the Blue Whale in Australian waters.

The flesh was removed from the carcass by museum preparators, who ensured that any cartilage attached to bone was kept as intact as possible. Maceration, which involves soaking the bones in water to remove soft tissue, was followed by bone degreasing at a special unit of the South Australian Museum. All individual items of the skeleton were numbered to ensure their accurate placement during articulation for display in the museum.

Three subspecies of Blue Whales are recognised. These are Balaenoptera musculus musculus from the North Atlantic and North Pacific, B.m.intermedia from the Southern Hemisphere, both referred to as "True Blues", and the smaller B.m.brevicauda, or "Pygmy Blue", known mainly from subantarctic waters of the Indian and south-western Atlantic Oceans. Each subspecies has special features and measurements. The Lorne whale has those of the Pygmy Blue Whale, Balaenoptera m. brevicauda.

Blue Whales were subjected to drastic hunting during the 19th and part of the 20th century. Their numbers dropped drastically and their status became extremely precarious. Exactly how many Blues were killed in the southern seas is difficult to determine, as the whaler fleets hunted both the True Blues and the Pygmy Blues. In 1966 all Blue Whales were accorded complete protection by the International Whaling Commission and their populations are now slowly recovering.

Blue Whales (B. m. brevicauda) were once thought to be restricted to the subantarctic zone north of the Antarctic Convergence - the region where the cold north-flowing Antarctic waters meet the warm south-flowing waters from the middle latitudes. Now we understand that they spend the summer south of the Antarctic Convergence. Recent surveys of Blue Whales along the Western Australian and Victorian coasts indicate that they may have an even wider distribution, and studies are in progress off Cape Naturaliste in Tasmania, Portland in western Victoria, and Perth and Rottnest Island in Western Australia. There are several real and potential threats to whales in this area, such as shipping, trawling, possible exploitation of krill, and undersea gas and oil extraction. Even whale-watching could become a threat if it were to be over-developed.

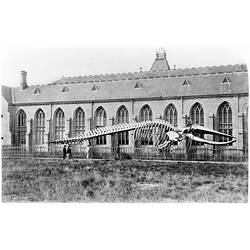

It is more than a century since a large Victorian whale skeleton had been displayed in Melbourne. In 1867 a whale skeleton was collected from Jan Juc. It was described as a Whalebone Whale by the then Director of the Museum, Professor Frederick McCoy. The huge specimen was exhibited in the open air outside the museum at the University of Melbourne. Unfortunately it deteriorated considerably in the many years it was exposed to the elements, and in 1899, when the museum moved from the University of Melbourne site to the Swanston Street premises, it was not put back on display. Although only a few items from this exhibit are still in the collections, it remains the largest articulated whale skeleton in the Southern Hemisphere.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types