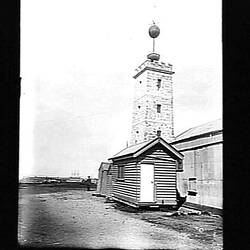

A primary function of Melbourne Observatory was to maintain standard time. Williamstown Observatory, its predecessor, had been established in 1853 with the express purpose of providing accurate time to ships' captains. By August 1853 the Williamstown Observatory was providing a time service at 1pm each day, by dropping timeballs erected on a flagstaff at Gellibrand's Point, Williamstown, and another at Flagstaff Hill in Melbourne. Ships' captains could observe one of the two timeballs with their hand telescopes, and adjust their chronometers at the fall of the ball.

Ships' captains needed to have accurate time to allow them to navigate accurately when at sea. By providing an accurate measure of local time at a known longitude, captains could adjust for any errors that may have crept into the instruments and their calculations after months at sea. In addition to the timeball dropped at 1 pm each day, the Observatory was also responsible for checking the accuracy of ships' chronometers and sextants, and making any necessary adjustments.

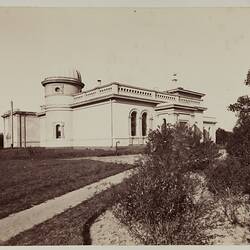

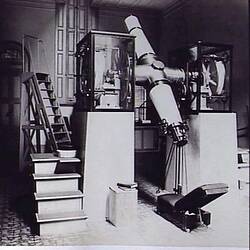

Melbourne Observatory time was established by using a transit telescope to observe the movement of 'clock stars' - stars whose positions were accurately known. Nightly observations made sure that the master clock in the Observatory was keeping time with the movement of the clock stars across the field of view of the telescope.

The demand for accurate time extended beyond the need to check ships' chronometers. The Argus newspaper in 1853 had complained: 'Never was a city so doomed to having great varieties of or variations in time as Melbourne; the truth being that there is no true or recognised, or proper standard of time in the place. . . The Post Office Clock, which should be, par excellence, the best and always right, is barely right, except twice in the twenty four hours by accident. Ten minutes slow one day, and the same number fast the next, is perfectly common with the only one recognised public clock in Melbourne, the writer once having seen the hands moved on fifteen minutes at one stretch'. (Davison 1993, 36)

Once the Williamstown Observatory was opened, a timeball was quickly established at the Telegraph Office in Melbourne, linked by telegraph to the Observatory, and this was used by Melbourne's watchmakers and citizens to check their timepieces. In 1870 a telegraph wire was erected between the Observatory and the city centre and used to control a clock at the watchmaker Thomas Gaunt's shop in Bourke Street. Within a few years the Observatory was also controlling clocks at the railway stations at Spencer Street and Flinders Street, the Post Office clock, Parliament, Customs House and several banks.

The railways became a particularly important mechanism for the distribution of Observatory time. A master clock at Spencer Street sent an impulse every hour to clocks at other stations on the main passenger lines. Station masters at the smaller branch line stations received a daily signal on the railway telegraphs to allow them to set their clocks accurately. Accurate time helped ensure that the railways operated safely, and railway time became an important source of accurate time for the whole community.

Nevertheless, time throughout the state was not uniform. Many towns preferred to keep their clocks set to local solar time, so that the local midday coincided with the Sun's zenith; this meant, for example, that Warrnambool was 10 minutes later than Melbourne. After discussions in the early 1890s, the separate colonies agreed to establish three standard time zones, based on the times at set meridians of longitude. On 1st February 1895 Eastern Standard Time was adopted; Melbourne's clocks went forward 20 minutes, while Sydney's were set back by 5 minutes. Some commentators saw the adoption of standard time as a sign of political maturity between the colonies, and as a positive step towards political federation.

The development of radio technology provided a new means to disseminate time. From September 1913, the Melbourne Observatory joined the Wireless Time Service established by the International Time Association, and a series of time signals were transmitted at noon and midnight from a radio station in the Domain. At first this was primarily used by ships at sea, but with the development of commercial radio in the 1920s, the hourly time signals became a familiar sound to the whole community. Radio signals made the Williamstown timeball redundant, and it was discontinued in 1926.

Melbourne Observatory retained responsibility for Victoria's time signals until it closed in 1944, when responsibility passed to the Commonwealth Government's Post Master General's Department.

References:

Davison, Graeme (1993). The unforgiving minute: how Australia learned to tell the time, Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types