Summary

The 25 blocks making up the Colonial Square sculpture at Melbourne Museum represent most of the ornamentation seen on the former Colonial Mutual Life building, one of the grandest ever built in Melbourne. The blocks give an indication of the scale of the construction and the superb workmanship that went into the stonemasonry. The magnificent carved capitals are especially notable. Most blocks on display can be sourced to a feature at a particular level on the building. The six pieces forming the northern cluster are from the two upper floors of the building, close to one edge. The central cluster is made up of random pieces, including a carved slab carrying part of the original lettering for the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the USA (this was subsequently covered by Colonial Mutual Life signs after the building changed hands in 1923). Pieces of pink Cape Woolamai granite from the portico make up the southern cluster, with one block from a section of the base-course.

A Grand Building

In the late 1880s, fuelled by riches from the Victorian goldfields, the price of land in inner Melbourne skyrocketed. In 1890, the Equitable Life Assurance Society of the USA paid £360 000 for a rectangular block of land, measuring 132 by 79 feet, on the NW corner of Collins and Elizabeth Streets.

Just over half a century earlier, in June 1937, the same blocks had been bought for just £64 at the first public auction of Crown land in Melbourne.

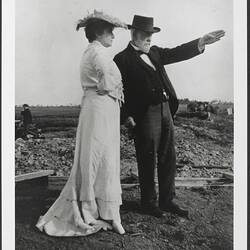

The Company wanted to erect the "grandest building in the Southern Hemisphere" and spared no expense doing so. A noted Austrian architect, Edward E. Raht, was engaged to design the building. The general contractor was David Mitchell, who had constructed many other fine Melbourne buildings. Four years and four months elapsed between the first contract for excavations, in November 1891, and the building's opening by the Governor, Lord Brassey, in March 1896. The foundation stone was laid in March 1893.

Raht opted for an 'Americanised Renaissance' style for the building. For such a mammoth construction, he wanted traditional materials in vast quantities, so contracts were let for local granite and imported marble. Like a palace, the building was supposed to last forever, so innovative construction techniques were needed to lift and lock together the giant granite blocks. When completed, the building rose to a height of 138 feet, with seven stories, and dominated the streetscape.

Grey granite quarried at Harcourt, near Mt Alexander, was used for most of the construction. Beneath the grand archway forming the entrance on Collins Street was a portico assembled from pink granite quarried at Cape Woolamai, on Phillip Island.

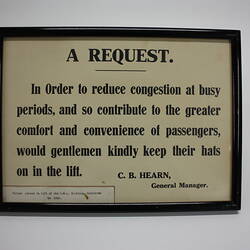

Blocks of this granite were also used for the base-course. Above the entrance was mounted a piece of symbolic statuary cast from metal. Corinthian columns spanned the 41 feet between the third and fifth floors. Some of the decorative friezes and capitals represented stonemasonry at its very best. The interior woodwork - ceilings, doors and window frames - was of the best cedar, joined to perfection. Not a nail was used anywhere. The interior stonework, mostly marble, was just as lavish.

White Italian marble was used for the floors and many walls. Elaborately carved and polished Belgian marble was used in skirtings, dadoes and architraves. The roof and downpipes were of copper. The all-up cost of the building was £233 000, including £72 000 for the supply of the granite.

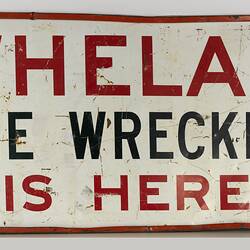

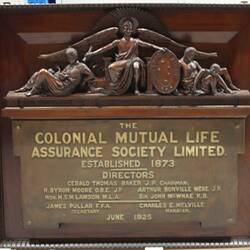

The Equitable Company occupied the building until 1923, when it was sold to the Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society Ltd. The new owners paid £280 000, less than half of the original total cost. Despite its status however, by the late 1950s the building was becoming uneconomic. While structurally solid, its very lavishness, especially its high ceilings, was its doom. Experts, including the National Trust, were consulted but, despite the building's grandeur and opulence, it was not considered worthy of preservation. In July 1959, CML's call for tenders for demolition was won by Whelan the Wrecker; by the end of 1960 the landmark building had gone. The contents of a copper time-capsule uncovered during the demolition were returned to the New York headquarters of the Equitable Life Assurance Company.

The new building erected in its place used some of the original grey Harcourt granite for exterior facing panels. Some of the interior marble fittings were sold for use in buildings elsewhere in Melbourne.

The statuary above the portico went to the University of Melbourne. Many of the original granite blocks had been purchased privately and survived until 2000, when representative pieces were acquired by Museum Victoria. They now form the sculpture on Colonial Square.

Harcourt Granite

Large masses of granite magma formed in central Victoria during the Devonian period about 390 million years ago. Mt Alexander, 25 km south of Bendigo, is the highest point of one of these masses, known as the Harcourt Granite after the nearby town.

Granite has been quarried on the slopes of Mt Alexander since the 1860s. It is one of the earliest continuously quarried building stones in Australia and is found in buildings in many major cities. At first it was used locally, then from the 1880s began to appear extensively in Melbourne buildings, either as the base or for ornamental and monumental stonework, such as columns.

Several quarries operate today, supplying stone mainly for cladding. Harcourt granite is one of the easiest stones to quarry, because it can be split readily into blocks of all shapes and sizes. This quality compensates for the dull grey colour of the stone, which tends to stain brownish in the city atmosphere. Harcourt granite is also disfigured by dark clots, which are a distinguishing feature.

Cape Woolamai Granite

A mass of pink granite forms Cape Woolamai, on the rugged eastern end of Phillip Island in Westernport Bay, about 130 km southwest of Melbourne. Along parts of the southern and eastern margins of the cape, the cliffs rise nearly 100 m from the ocean. On the northern edge however, the granite slopes more gently seaward.

It is here, in 1891, that a quarry was established to obtain granite for buildings in Melbourne. The plug and feather method was used, with seawater causing the wooden plugs to swell and the rock to split. A jetty was constructed of granite blocks and used to load boats. However, in December 1892, the heavily laden ketch Kermandie disappeared at sea and quarrying ceased soon after. It is possible to walk to the quarry site today, where blocks up to 2 m long are stacked at the old jetty. As far as is known, the Equitable Life Assurance building was the only Melbourne building constructed from Cape Woolamai granite. Pieces weighing up to 10 tonnes were used to make pillars and blocks for the base-courses and portico. The pleasing pink colour of the granite is due to thin films of reddish iron oxides in feldspar crystals. The granite also takes a fine polish and is remarkably resistant to crushing.

Demolition

Just as the construction of the CML building was a monumental exercise, so was its demolition. The interior timber and marble fittings were stripped first and sold off. Whelan the Wrecker then had to develop special techniques to handle the giant blocks forming the shell of the building.

Each block had to be angle-drilled then pinned in order to hoist it from its position and lower it to the ground. The largest capacity crane in Melbourne at the time was specified to lift only seven tonnes but handled blocks weighing eleven tonnes. Holes were punched through each floor so that the blocks could be lowered safely internally and not above the street. The keystone above the portico could not be removed intact and had to be jack hammered away. It took nearly twelve months to bring the building down and while seven lives were lost during construction, none was lost during the demolition.

Statuary

The metal statue mounted over the portico showed an angelic figure protecting a youth and a young mother with an infant. Commissioned by the Equitable Life Assurance Society, the statue was sculpted by an Austrian artist, Victor Tilgner (1844-1896), and cast at the Imperial Art Foundry in Vienna.

When the original building was demolished in 1960, the statuary was presented by Colonial Mutual to the University of Melbourne. For many years it was situated on the University's School of Architecture property at Mt. Martha, on the Mornington Peninsula, before being moved to the Carlton campus in 1981. It was installed between the South Lawn and the Baillieu Library and is now a permanent feature of the landscape.

Acquisition by Museum Victoria

After the demolition of the Colonial Mutual Life building in 1960, the granite blocks were purchased privately. Over the years various pieces were sold off and the remaining blocks were moved several times. Eventually, they came to be stored at Laverton North, about 15 km west of Melbourne.

In the mid-1990s, the land the blocks were occupying was compulsorily acquired by VicRoads, the authority responsible for freeway construction. The authority agreed to allow the Museum to acquire selected pieces showing the range of ornamental features. Twenty-five blocks were chosen and moved to the Melbourne Museum site in Carlton in May 2000. The remaining blocks were destined to be crushed.

More Information

-

Keywords

Public Art, Public Institutions, Insurance Industry, Banking Industry, rocks (geology), Public Parks, mining

-

Localities

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, Victoria, Australia, Australia

-

Authors

-

Article types