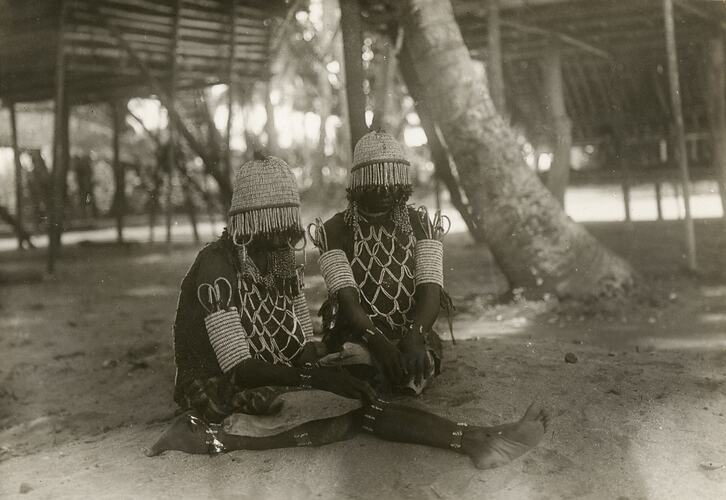

Women from the Oro Province of Papua New Guinea undertook extensive periods of seclusion to honour and grieve the death of their husbands. A nation of 8 million people with 1000 cultural groups and over 800 languages, Papua New Guinea is made up of matrilineal and patrilineal societies. Cultural groups residing in Oro Province are largely patrilineal and the custom of making beautiful adornments that embody the emotional weight and shock of grief were primarily reserved for mourning the death of a woman's husband.

Upon the death of a husband, a man's wife or wives would go into a period of seclusion. In Orokaivan language, one of 25 languages in Oro Province, the living partner of the deceased is referred to as Pamone Doru, if they are female. If the husband is grieving the loss of his wife, he is referred to as Ivu Doru. The amount of time the widow spends in seclusion would've been dependant on the season and abundance of food, this could be anywhere from several months to a year. The widow would not be seen or heard by other villagers. If she needed to make a public appearance, her head would be covered by a piece of bark cloth.

During this grieving period the widow's relatives would help gather the seeds and fibre needed to make garments for the body. Fibre would be sourced from the bark of trees to make the twine and woven into a shape fitted to the woman's body, hours of laborious work alone. Thousands of Jobs Tears seeds (coix lacryma-jobi) would be gathered from plants that grow close to the rivers in the Oro Provincial region. The Jobs Tears seeds are meticulously cut in half and thread onto twine to create desired patterns, similar to beadwork.

The time spent in seclusion with family members and repetitive actions of twisting, weaving and threading to make garments such as this would have been a form of healing through a difficult period given the historical cultural context of being a widow. During the time of when this practice existed, a woman without the protection of her husband would have been in a vulnerable position within a patriarchal society to survive.

This garment along with a head covering (X 007434) were worn only once the widow/s came out of seclusion. The mourning garments communicated to people in her village that she was still in a period of mourning her husband and was able to retain a level of privacy with the veiling of her eyes whilst being physically visible in the village. The design and detail of each garment is individual to the grieving widow/s. A public indication that the grieving period had ended is the removal of the mourning garments as an emotional and physical release. Whilst these items are associated as a historical custom, the making and wearing of these grieving garments is no longer practiced today.

The adoption of Western culture in Papua New Guinea has significantly changed and affected the spiritual and cultural practices and languages of its people. The introduction of education in Papua and New Guinea as a mandated Territory of Australia (1906 - 1975) along with Anglican missions, forced many children from Oro cultural societies to relocate outside of their villages. Despite education being supported by Oro families it was a detriment to the passing on of cultural knowledge to the next generations. Other forms of grieving practices can be seen throughout Papua New Guinea today that utilise the same Jobs Tears seeds in necklaces and the smearing of clay or ochre on a woman's body as a sign of mourning.

This information was gained through a cultural workshop held at Museums Victoria in October 2018, specifically for Oro Women living in Australia, with cultural knowledge support from Professor Russell Perembo, University of Papua New Guinea. The text written here was largely drawn from the knowledge of elders Ayn Sunana and Russell Perembo, authored by Museums Victoria staff member and Papua New Guinean woman, Lisa Hilli.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types