Open-cut mines in Gippsland are the main source for coal in Victoria, quarried from some of the world's thickest brown coal deposits. This coal formed from a wet and humid forest, beginning around 40 million years ago and becoming thickest by around 18 million years ago, during the middle Miocene Epoch. Average temperatures in the Miocene were around 5°C warmer than present day, and the resulting higher sea levels made areas like Moe, Morwell and Traralgon near-coastal. Brackish water flooded the forests and left soils waterlogged, converting them into peat swamps.

In total, the coal seams are hundreds of metres thick, but were never buried deep enough to compress and transform the original peat into black coal (anthracite). As a result, leaves, fruits, branches and whole tree-trunks were preserved. These fossils show the area hosted dense forests of southern beech (Nothofagus), araucarian conifers, and other rainforest species. Giant fossil Kauri pines found at Yallourn, near Moe, match trees now found in the rainforests of Queensland, Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Reeds, mosses, ferns, liverworts and sundews were found in the forest understorey.

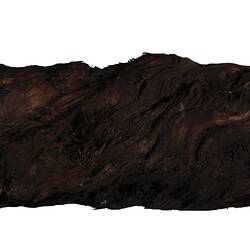

Bands of charcoal are found throughout the brown coal seams, preserving evidence of ancient bushfires caused by lightning strikes. Charcoal is doubly useful in the fossil record; as well as evidence of fire, it preserves plant structures at much higher quality than coal or peat, allowing detailed study and identification. Closed forest habitats with large trees were least impacted, but charcoal from aquatic reeds is common, and indicates that fires burned through lowland areas for tens of kilometres.

Australia's climate dried out significantly at the end of the middle Miocene, marking the end of the peat swamps in Gippsland. Much later, during the late Pleistocene Epoch, circumstances led to a second stage of fossil deposition in the seam. In the 1970s, workers in the Morwell No. 2 open-cut mine found lenses of clay buried within the coal seam, from what would have once been still, deep ponds. These ponds may have filled the spaces left behind when fires burned coal seams millions of years after they formed. Study of fossils preserved in the firehole ponds showed they were covered by floating plants (Azolla), and populated by snails, crustaceans and galaxiid fish. Most exceptional, though, were the complete fossil remains of Pleistocene kangaroos, preserved at the base of the pond deposits.

Skeletons of the extinct heavyset browsing kangaroo Protemnodon were found, including pouch young and joeys at foot. As well, the fossil remains of the still-living eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), and a similar but distinct new species, Macropus mundjabus, were also preserved in the firehold ponds. Sulphurous sediment and decomposing vegetation drew oxygen from the pond waters, excluding scavengers and drastically slowing bacterial decay. As a result, many of the kangaroo skeletons were fossilised with bones in life position (articulated), and even with gut contents and impressions of skin and fur preserved. In particular, fossils of M. mundjabus preserve the pattern of hair follicles in its coat. Compared to modern eastern grey kangaroos in the area, M. mundjabus had a woollier coat. Today, the fur of kangaroos varies dramatically with local conditions, and M. mundjabus may have been adapted to colder climates during the Pleistocene.

The pond deposits that preserved these marsupial fossils now leave them at risk. The black clays have formed sulphur salts and in places broken bones apart as they dried, shrunk and cracked. Museums staff and volunteers have painstakingly removed from bone surfaces the glues used to preserve them at the time of collection, allowing them to be cleaned and newly strengthened. This process will ensure the fossils remain stable for generations of study to come, as well as for display in exhibitions.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types