Summary

Hendrika Perdon (late Schwab) recounts her memories of growing up in Occupied Rotterdam during World War II.

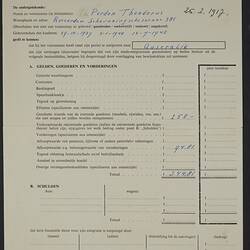

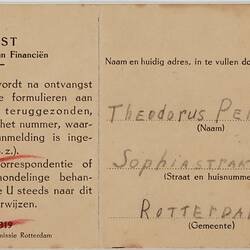

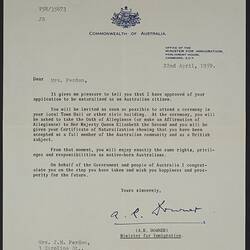

The following is the story of Hendrika (Ricky) Schwab (nee Perdon), daughter of Johanna (Ann) Perdon as written by Ricky for her daughters Susan Allen and Chris Cairns in 2016 and provided to the Museum in 2019.

Bombing of Rotterdam:

'Even though I was born on the 29th October 1937 my first recollection of my life was sitting on the steps of St Franciscus Hospital on the Schiekade in Rotterdam, when I was approximately two and a half years old.

The Luftwaffe (German Air force) was bombing Rotterdam and my mother Ann had taken refuge in the hospital. A bomb had fallen in front of our flat (everyone lived in flats in the city). My mother grabbed my brother Bill, who was three months old, in her arms and with me holding to her skirt, she then stepped over the unexploded bomb and starting running towards the outskirts of the city and the hospital. The bombs were falling all around us and the streets were on fire. My mother told me later that I was crying and asking her to lift me but as she was holding Bill I just had to run with her.

My grandmother lived not far from us and took refuge under a railway viaduct. The bombing went on all afternoon and my mother told me that at one o'clock in the afternoon the sky was black as though it was midnight. Thirty thousand people died that day. After the bombing, Holland capitulated. My mother had lost everything. There was not even a nappy for Bill.'

We Had Nothing:

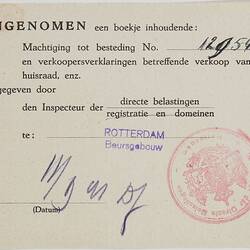

'My grandmother in the meantime found an empty flat near the hospital and moved in. She contacted the owner and rented it. Grandma (or Oma to us) told my mother she could have the flat because she had decided to go to The Hague and as my aunt Mary was still at home she went with Oma. We obviously had nothing. The Government helped people with money, to get started again. My mother wisely immediately spent all the money on all the things we needed because as the War had started it became immediately apparent there would be shortages.

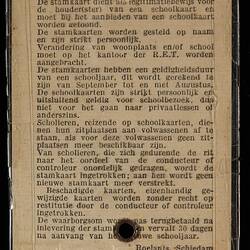

From then on coupons were introduced. Not only for food, but everything. You could not buy clothes or anything without coupons. Later on in the War, even with coupons and money, you could not buy anything due to the fact that we were an occupied country. The Germans took everything from Holland e.g. gold, silver, bikes, food from the farms, so there was less and less to survive on. People took to eating everything including cats and dogs.

My brother Theo was born in 1942 and my mother could only get milk for him until he was six months old. She received coupons for nappies, but they were unable to be purchased. The man in the store told mum all he had was some white imitation silk left that he would sell for money and the coupons which my mother took. Oma asked mum to sell it on the black market for her for food, but mum declined and later that material became my first Holy Communion dress. I was the only communicant with a long white dress and flowers in my hair.'

Just Surviving:

'Besides the obvious hardships from extreme shortages life was precarious. There were regular bombings. I spent a lot of time in the Hague with Oma and if there were bombings I was taken out of bed and with a blanket around me we would spend the duration of the bombings on the staircase (because that is the strongest part of the house). After the all-clear siren sounded the little café over the road would open up and quite a few people would go over for a bit of T.L.C. and a gin or so to calm their nerves. The ladies put a teaspoon of sugar in their gin and I was allowed to eat that. No wonder I slept.

Oma was a battler and she used to go to Toeternels, a second hand dealer (it looked exactly like a shop straight out of a Charles Dickens novel). Oma would go through old jumpers and old coats and would unpick these items, wash the panels of the coat or unravel the old jumpers and make new jumpers, or turn the panels of the old coat and make new clothes. Oma was a great innovator and a good dressmaker.

In the meantime my father worked in the Catholic hospital (Saint Franciscus) not far from our house. At night he would bring a small saucepan of potatoes mashed with fat and that kept us going that last hunger winter 1944-1945. There were soup kitchens which we would go to but it was more water than anything else, my brothers refused to eat it, but I did and in my memory it tasted sour. Until the War finished we had never tasted nuts, oranges, bananas, chocolate, chewing gum, etc.'

Forced Labour:

'When the War started all the young men of a certain age had to go to Germany to work. My Uncle Bill (mum's brother) took both his guitars and a suitcase full of clothes. When the War eventually finished, he was on a forced march in France when he collapsed on the side of the road. Eventually a lady doctor found him and took him to the local hospital, three months after the War finished. We all thought he had perished. He returned dressed in a pair of ski pants and top from that lady doctor. She really saved his life. All the clothes and guitars etc. had been stolen from him.

My other uncle Jan van Nieuwkerk (he eventually married my mother's sister Mary) fared a lot better. When he was transported by train to Germany he jumped off the train and lost himself in the population, and spent the rest of the War working and looking after the fraulines (German girls) and working as a plumber.

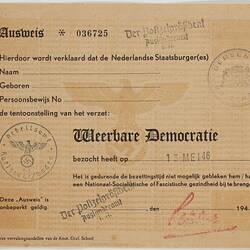

There were also 'razzias'. Because all the men of a certain age had to go to Germany to work in the factories, a lot of men tried to hide out, either in between the floors, for example the first and second floors, or behind false walls either in the attic or behind cupboards, walls in kitchens or anywhere else they could find.

When a razzia occurred a platoon of German soldiers would cordon off a whole street block, so nobody could get in or out. Then they would enter each house in that street and look around for hiding places for men. If they were found these men would get herded out onto the street. They were either put on a truck without any extra clothes, or they were rounded up to a corner of a street and shot. Then all the Dutch people were forced to walk past. This would sound as a warning to the people of Holland to obey the German High Command. A lot of the men would hide behind false walls in the attic and cellars, in behind kitchen cupboards and between the floors.

One day this happened in our street, this German soldier banged on the door of our flat and demanded to know if there were any men on the premises and also enquired of my mum who lived upstairs. My brother Bill who was five at the time was hiding behind a chair, because he knew these soldiers were looking for men. The soldier saw the movement behind the chair and pulled his Luger revolver and pointed it in the direction of my brother, yelling out 'Wass ist das?' My mum immediately pulled Bill from behind the chair explaining to the soldier that young Bill knew they were looking for men.

My mum told the German soldier that there was an old couple living upstairs and no one else. The German then grabbed mum and started kissing her. My mum was very attractive and we children were very scared what would happen to her. Just then another soldier called up to his mate and told him to hurry because they had to leave.

Much later my mum found out that the old couple upstairs had sublet their attic room to a pair of dental technicians and they had another three men hiding up there with them. If it wasn't for the fact that this soldier had been distracted from investigating further, God only knows what would have happened to us if these men had been found after my mum denied anybody else was on the premises.'

Desperate Shortages of Food and Fuel:

'When Oma went on live in The Hague she obtained a flat on a corner above a tobacconist and a grocer. The grocers in those days were not self-service. You gave the girl behind the counter your order and she would measure a pound of biscuits from a big tin. No pre-packaged food. I remember my girlfriend buying a bag of biscuit crumbs and pieces for 10 cents. They were the left overs in the large tin of biscuits.

Oma told us one day towards the end of the War that some Dutch people (by this time there was virtually no food left in the big cities) raided the grocer shop for food. When the Germans arrived they managed to catch only one person, a young boy of fifteen. The German Soldiers made him dip his finger in an ink pot (biros did not exist in those days) and he was made to write on a piece of cardboard: 'I AM A THIEF'. They left this young boy without food or drink holding up this cardboard for three days and nights, and then they shot him.

I was not able to attend school the last winter of the War because there was no heating, so once a week my mother and I used to go to school and pick up homework and she would help me. That last winter of the War the Germans turned off all the power and gas. People could not keep warm. It was the coldest winter for 50 years. Some people got a tin of some sort and cut a hole on the bottom side for air and tried to cook a little. For light my father brought home a carbide lamp that is a fairly heavy cylinder, about 20 centimetres high and had a wick running through it. It was then placed in an iron receptacle with some carbide stones in water and subsequently lit. It gave off a feeble light. Every now and then it used to explode and scare the daylights out of us. There were also blackout blinds on all the windows, they were made of paper, and if any light would shine through the German patrols roaming the streets would shoot your windows to pieces. This was quite devastating as there were no tradesmen or materials.'

A Perilous Journey:

'During the spring in 1945 my mother and a friend decided to go to the farms with goods to swap for food. The farmers did not want money because it had no value. So mum had sheets and clothes (including a little blue dress, which I am wearing in one of the photos; it has a little Chinese collar) and on a bike without tyres, Tyres were not available as all the rubber was imported and now confiscated by the Germans. She half walked and rode right up to the north of Holland, for example Groningen and Friesland, and they used to sleep in the hayloft with a lot of other people doing the same thing. She came back with a hessian bag of potatoes inside of which she had some grain and six eggs. By this time her 'shoes' had worn through after all the soles were made of some sort of cardboard.

When she got to the bridge at Nijmegen, the Germans had closed the bridge and the people were told not to cross because they would be shot. My mother told the German soldiers that she had three young children in Rotterdam and she had no choice but to cross. Well she made it across. That night she arrived at approximately 11 o'clock. That was very dangerous because curfew was six p.m. Then she had to wake up our father which she told us took 20 minutes because she had to ring the bell, and that was very hazardous because we lived on the first floor and it was a pull bell and very loud. Besides it took my father a while to wake up.

While my mother was away (ten days) my father used to take us to another couple on the other side of the viaduct (that our house faced). Pa used to take a colander filled with potatoes and onions for us to eat at lunch, which would have been plenty for us, but these people used to give us the tiniest saucer of food and keep the rest for themselves. Then they would insist we had to go and play outside. Because of the War situation there was no one to play with because people would keep their children inside. So for the whole ten days we would sit outside on the door step and not be allowed inside. I have never been more grateful for mother to come home.

My brother Theo was born in 1942. For six months mum had coupons for watered milk for him as our mother could never breastfeed us but after that period there was no more.'

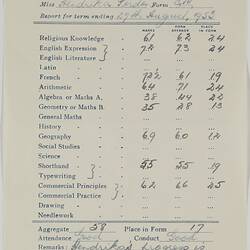

Sent Away to School:

'Four months before Theo was born my mother sent me to a boarding school, her explanation to me was that I was not a good eater and they would make me eat. I never believed that story, but I was very unhappy there. I used to sit there with my thick slices of bread for ages after everyone had gone to play. On Sundays I used to have visitors, Oma would come and Mary, my aunt, and I would beg them to take me home. My mother turned a blind eye to my begging and left me there. When I eventually came home I was so grateful that I was scared to cross her in case she would send me back. I was at that stage not yet five years old.'

Final Reflections:

'During the War years I spent quite a lot of time at my grandmothers' house in the Hague. Mary was still living at home and she was good fun. Oma used to drag me around wherever she went. In the summer we went to kindergarten. It was called a Montessori class and very advanced for its day. There was no soap, no toothbrushes (but as there was not much to eat I don't think there was much to clean), no sewing cotton, no buttons. Everything was used from a more meagre supply each day.

One day an allied plane was shot down by the Germans and headed straight towards our flat, you could see the pilot, who at the last minute managed to pull up the plane over our flat, over the rail viaduct and into the street onto the other side where he slid into canal. Because of that he saved he saved all our lives. After the War the Dutch Government honoured him with a monument.'

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types