Summary

Alyana Eau describes her journey of trauma and hope from Iraq to Australia. Alyana is one of the artists represented in Attache Case, a collective artwork in the Museum's collection.

Background:This piece was written for the Museum in 2025 by Alyana Eau, one of the artists who contributed to the collective artwork Attache Case now in the Museum's collection. Alyana's powerful and poignant memories of the trauma of war and displacement include some details that may be distressing for some readers.

Introduction:

'My name is Alyana. I was born in Zakho, a small town in Iraq near the Turkish border. It was a place full of warm memories - climbing trees, running through the streets with friends, the smell of freshly baked bread drifting from our neighbour's homes. Life felt simple, full of promise.'

Lives Shattered:

'But on March 12th, 1991, everything changed. The sounds of gunfire shattered the peace. I remember standing in the garden, looking up at the sky. It grew dark and heavy, as if the whole world was holding its breath. Then I noticed a tall man at our front gate - a family friend. I overheard his urgent conversation with my father: we had to leave immediately. Living near an army base, we were in imminent and growing danger.'

Fleeing in the Night:

'That night, we packed whatever we could carry and fled to my grandparents' house. I remember the streets of Zakho - so lively only days before - now deserted, the empty windows of homes staring down at us like hollow eyes. Fear hung in the air like smoke.'

'At my grandparents' house, the atmosphere was tense. Lights were kept off, curtains drawn tightly shut to avoid being mistaken for the resistance and targeted. It felt as if we were buried within those walls. I was gripped by a new, overwhelming fear - not just of dying, but of losing my family, of waking up one morning and finding myself completely alone.'

'I curled up under a pile of pillows, listening as my family tried to guess where the bombs were falling, judging by the tremble of the house and the intensity of the blasts. Their voices faded into the background, and eventually, I drifted into a troubled sleep.'

Aftermath:

'The next morning, there was a terrible stillness - the kind that comes after a storm but before another begins. The bombings had slowed, but the danger remained. When my uncle stepped outside to check on neighbour's, a mortar shell struck and killed him. He was the youngest uncle - a loving man, a father, a husband.'

'Time seemed to stop. The world collapsed in an instant - screams, confusion, disbelief. My uncle's family fled Iraq shortly after. My grandparents were never the same again. The warmth of their home seeped away, leaving only cold walls and heavy silence.'

'The front gate was never repaired. It still bore the jagged scars left by the mortar shell - visible reminders of the violence that had torn our lives apart. We visited often, peering through those holes, remembering that terrible day. Over time, those holes became part of our family's memory. When we looked through them, we sometimes caught glimpses of life moving on - small, ordinary moments framed by destruction.'

'Eventually, my grandparents died of grief. The broken gate outlived them - a silent witness to everything that had been lost. In 1998, my family fled Iraq.'

First Stop Turkiye:

'Our first stop was Turkiye, but we couldn't stay there - our visa had expired within less than a month of arrival and returning to Iraq was not an option. Desperate for safety, we tried to escape to Greece. Along with 20 other Iraqi families, we hired a smuggler - the Kachakhchi - paying a large sum, hoping he could help us cross the border. On our first attempt, the smugglers loaded us onto the back of a truck - a cramped cattle transport. We were driven from Istanbul to a small village, hidden in a barn and told to stay quiet until after midnight. The smugglers returned demanding more money, threatening to abandon us. In panic, we paid, but they still refused to continue, leaving us stranded in the middle of nowhere.'

'One smuggler stayed behind, promising to help us cross the border. Uncertain but desperate, we followed him into the night. Hours later, we reached a closed tea house - a Chaikhana - tucked away in a quiet village. An elderly Turkish man answered the door, his face lined with confusion and fatigue. Too weary to argue, he silently waved us inside. As we stepped in, the biting cold gave way to the warmth of the tea house, where the rich scent of brewing tea and lingering tobacco smoke wrapped around us like a memory of normal life - fleeting, delicate, and achingly familiar.

Failed Escape:

'We continued our journey, only to be surrounded by the Turkish border police, the Jandarma. With guns pointed at us, they shouted, "Otur!" - sit. We were arrested and taken to a military compound. It was past midnight, a bitterly cold night. They kept us outside, guarded by heavily armed soldiers, and lined us up in rows as an army tank was driven toward us, its turret aimed directly at our group. The soldiers stood nearby, speaking casually, as if our fear amused them. We were in shock, convinced we wouldn't survive.'

'For over thirty minutes, we stood frozen, watching the tank being prepared. A blinding light struck us, erasing the soldiers' faces, as if opening a portal to somewhere safer. We were told to stay silent, the last whispers of our loved ones barely audible.'

'They stripped us of everything - photographs, keepsakes, journals - and interrogated the adults, demanding to know who the smuggler was. Most of us didn't understand Turkish, and those who did stayed silent, afraid they might be mistaken for the smuggler.'

'They separated the women and children, forcing us to sit while they tortured the men, soaking their legs in freezing water. We watched, helpless and terrified, as no one broke. Eventually, they dragged the smuggler away, his cries echoing through the compound. We huddled together for warmth, too afraid to move, until morning. Then they loaded us onto army trucks, telling us we were being returned to Istanbul. The smuggler was brought out, his face swollen and unrecognizable - a chilling warning to us all.' Escape to Greece:

'Back in Istanbul, returning home wasn't an option. After three days, we found a new smuggler, paying half upfront, with the rest promised upon reaching Greece. The ordeal had taught us to be cautious - the smugglers sought money; we sought survival.'

'This time, the smugglers gathered the families, including new ones, and packed us onto a truck. They drove to a remote area, away from border patrol, and ordered us to walk in silence. The ground was slippery; thick mud clung to our shoes, each step heavier than the last. We trudged through the dark, our legs aching and frozen, unsure if we would make it. Eventually, we reached a body of water between Turkiye and Greece, following the shoreline until we found a narrow, calmer spot. None of us could swim, and there were no life jackets. The smugglers quickly loaded us into small inflatable boats, urging silence to avoid being spotted or shot.'

'Each boat held about eight people; families separated to fit as many as possible depending on weight. I was lucky to be with two of my siblings. But by the time it was our turn, the boat had a puncture. Water filled it as we moved, and we had to scoop it out with our hands. We made it across - wet, shaken, but alive. We looked back, praying for the others to arrive safely.'

'Once reunited, the smugglers gave us directions to find Greek soldiers and seek refuge before disappearing into the night. We walked through the early morning light, a soft sunrise glowing over us, until we met a Greek farmer who helped contact the authorities. It was our first real step toward safety, a step into a future we had barely dared to imagine. We had made it to Greece.'

Life in Greece:

'The train ride was beautiful - forests, mountains, wide open landscapes - and for the first time in a long time, we felt a small sense of hope. But life in Greece wasn't easy. We had no rights - no way to study, work legally, or seek asylum. Our hopes stretched farther, toward countries like Australia, the USA, and Canada. Each experience carved invisible holes in us - places of loss, terror, and resilience.'

'We didn't speak Greek and could only find laborious jobs. My parents, considered too old for manual work, struggled to find anything. Eventually, my sisters and I found jobs in clothing factories, where discipline and survival were the daily lessons. We worked not for our own dreams, but for our family's survival. The last job I had was in a knitting factory.'

Finally Australia:

'The work was repetitive, and my mind often drifted - to a life beyond the machines, beyond the endless rhythm of threads. Yet I stayed focused, determined to keep the thread unbroken - a symbol of everything we were fighting for. Life felt like that thread - fragile but moving forward. My father worked tirelessly behind the scenes, applying for asylum in Australia. One day, the call came: we had been accepted. The fog we had lived in for so long lifted, revealing a future. It was more than relief - it was victory.'

'Every sacrifice, every moment of fear, had woven us into something stronger, unshakable, ready to step into the light of a new life in Australia.'

Artwork: 'Waiting 1991 Gulf War - Zakho Iraq':

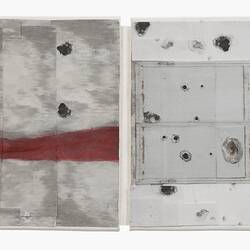

'The artwork I created that is part of Attache Case (and now in Museums Victoria's collection) was about the holes in my grandparents' gate - they are not just marks of violence, but openings through which memory, sorrow, and hope pass. Each hole represents a wound, but also a window: a reminder that even when something is broken, it can still hold light, still bear witness, still tell a story.'

'My artwork invites viewers to consider how trauma leaves its marks - not only on places, but on people - and how those scars, though painful, can frame resilience, memory, endurance, and survival. It reflects the power of hope and perseverance in the face of overwhelming odds, and the pursuit of a better life.'

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types