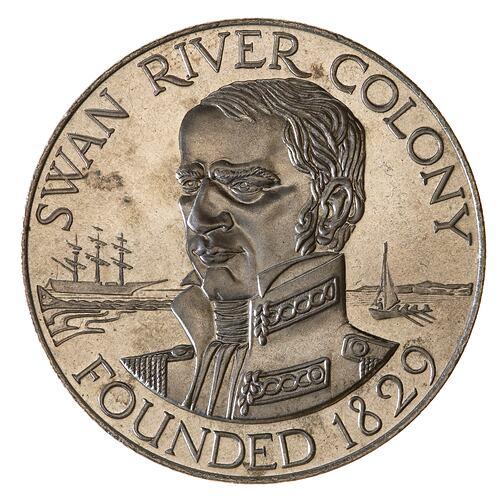

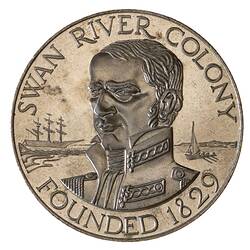

James Stirling was born into a privileged Scottish family in Lanarkshire in 1791. At the age of 12 he entered the navy as a first class volunteer, embarking on the storeship Camel for the West Indies. He was fortunate to have the patronage of his uncle, Rear-Admiral Charles Stirling. Soon after arriving in the West Indies he transferred to the Hercules and later transferred to his uncle's flagship, Glory. He saw action against the French and Spanish fleets. Following further military action he was promoted to lieutenant on the Warsprite. In 1812, at the age of 21, he received his first command, the sloop Moselle, and soon after the larger sloop Brazen, in which he harassed forts and shipping during the Anglo-American war. His uncle was prematurely retired from the service after being court-martialled for corruption, and when Bonaparte was defeated Stirling's prospects further dimmed. In 1818 he was placed on half pay. On his prize money from military actions and Treasury pay he was able to travel in Europe and move in elevated social circles. In 1823, at the age of 33, he married 16-year-old Ellen Mangles. They eventually had five sons and six daughters.

In 1826 Stirling was given the command of the Success, with instructions to take a supply of currency to Sydney and then to move the Melville Island Garrison to a better location to better defend the Pacific against French colonisation. On arrival he was granted 2,500 acres by Governor Darling. He persuaded Darling to allow him to examine the west coast of Australia to see if it provided a suitable site for another garrison or settlement to open trade to the East Indies. Stirling sailed in 1827, and was particularly impressed by land in the vicinity of the Swan River, as was the New South Wales Government Botanist, Charles Frazer. Frazer's reports added political and commercial weight to Stirling's arguments in favour of immediate acquisition of the region and Stirling's appointment to establish a new colony there. Governor Darling supported the plan, but the colonial administrators balked at the cost. Stirling was invalided to England with a severe stomach ailment, giving him a chance to press for the Western Australian settlement. In London his arguments attracted investors and speculators. In May 1828 Sir George Murray, a friend of the Stirling family, took charge of the Colonial Office, and it was decided to establish a colony under the direct control of the British government, superintended by Stirling.

On 2 May 1829 Captain C.H. Fremantle of the Challenger took possession of the whole of Australia that was not then included in the boundaries of New South Wales. Stirling arrived later with his family and civic officials in the Parmelia, and proclaimed the foundation of the colony on 18 June. Stirling administered the Swan River settlement from June 1829. Appointed as lieutenant-governor, he became governor in 1831. In August 1832 he took an extended visit to England and was knighted, taking the opportunity to advocate on behalf of the settlers. He returned to administer the settlement from August 1834 to December 1838.

In the early years of his administration, Stirling took part in exploration of the coastal districts surrounding the settlement. He also personally welcomed new settlers and was attentive to settlers' complaints. He faced the realities of the ill-planned settlement when starvation loomed, and was forced to buy emergency supplies from the Cape and Van Diemen's Land. He also supported the severe punishment of the small First Peoples population, including the Pinjarra Massacre, in which 14 First Peoples and one policeman were killed. The land also proved poor and difficult to cultivate and as a commercial and agricultural enterprise the settlement was a failure. In spite of these circumstances Stirling observed English customs and dress befitting his station, even when dining in oppressive heat and in tents.

Stirling was lampooned in the British press and at times strongly criticised for his inept administration and domineering attitude towards his civil officers. He lacked humour and was considered erratic and blundering in his approach to land policies. He tried to do too much, and much of what he did was badly done. The dignified and charming manner of his wife, amidst her many pregnancies, did much to soften his local image, but she was anxious to return to England.

Stirling resigned in October 1837, amidst severely strained relations with leading settlers and troublesome First Peoples relationships. By 1839 the settlers had still only developed a bare-bones rural economy that included the export of a few hundred bales of wool and whale oil.

On his return to England Stirling was appointed to further navel commands, but never lost an opportunity to speak in support of the Swan River Colony. In 1851 he became a rear-admiral, and next year served at the Admiralty. At the same time the British government was arranging the transport of thousands of convicts to Western Australia as the only means of saving the colony of 6,000 people from perpetual bankruptcy and stagnation.

Stirling continued up through the naval ranks, becoming admiral in November 1862. He died in comfortable retirement in Surrey on 22 April 1865, at the age of 74. His wife survived him by nine years.

References:

Australian Dictionary of Biography website http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/adbonline.htm

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Localities

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, Western Australia, Australia, England, United Kingdom

-

Authors

-

Article types