Sir Frederick McCoy, professor and museum director, was born in Dublin in 1817. He began medical studies, but soon changed to palaeontology and natural history. From the age of 21 he began publishing prodigiously in learned journals. Three years later his catalogues of the Dublin Geological Society's museum collections, and the shells and organic remains in the Sir collections of the Dublin Rotunda, were published. With these credentials he soon began work with Sir Richard Griffith, classifying Irish fossils, then in 1845 joined the staff of the British Geological Survey. A year later he was selected to classify fossils at the Woodwardian Museum, Cambridge, where Alan Sedgwick remarked that he was an 'excellent naturalist' and an 'incomparable and most philosophical palaeontologist'.

In August 1849 McCoy became professor of geology and mineralogy and curator of the museum at Queen's College, Belfast. Five years later a committee in Melbourne chose him to be one of the four initial professors of the University of Melbourne, which opened in April 1855. McCoy accepted, migrated to Australia and lectured in chemistry, mineralogy, botany, anatomy, physiology, zoology and palaeontologist. He favoured systematic teaching of compulsory classics, using theoretical rather than practical tuition. His approach was not universally well received, and students complained of 'botany in the lecture room and not in the garden'. McCoy was a naturalist who preferred to stay indoors.

A government museum collection had been established in 1853, but was now in storage, and McCoy arranged for the University to provide accommodation. The Philosophical Institute (later the Royal Society) of Victoria argued against the collection's move from the city and probable control by the University, but McCoy triumphed, and in December 1857 he was appointed Director of the Museum of Natural and Applied Sciences. He held this office without pay for the rest of his life. Fortunately, in 1856 he had become government palaeontologist, providing him with a salary. In 1864 a new building was opened on the University grounds to house the collection, now called the National Museum.

McCoy built up an outstanding natural history and geological collection, often with little regard to expense. In 1870 the Museum was placed under the Public Library trustees, and the struggle to make him docile began. Public attendances continued to climb, however, with 95,000 people visiting each year during that decade. McCoy made further mistakes, including becoming a leading member of the environmentally disastrous Acclimatization Society. He urged the 'enlivening' of the 'present savage silence' of the bush, and rejoiced at the sounds of the English songbirds that had been released. He even celebrated that the rabbit was 'so thoroughly acclimatized that it swarms in hundreds in some localities'. McCoy also visited the goldfields and disparaged 'ignorant miners' seeking gold at 'heretical depths'. His own ignorant remarks were later considered a blot on geology. He also opposed the theories of Darwinism.

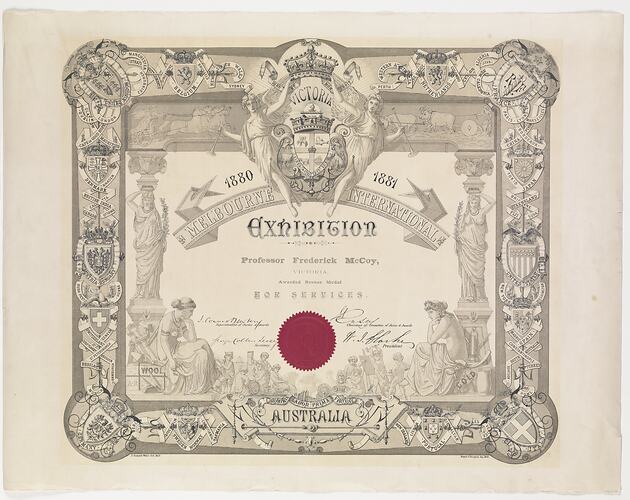

McCoy served as a member of the Council of the University 1882-87 and a member of the Royal Society of Victoria Council, and later as Vice-president and President. He was a Commissioner for the Victorian, Intercolonial and International Exhibitions, and was awarded medal NU 23852 for his services at the Melbourne International Exhibition (Official Record, p. xviii). He also sat on Jury 1 for that exhibition, assessing artworks including oil paintings, drawings, lithographs and modelling (Official Record, p.21). McCoy strongly supported the causes of education and research. He received many European and Australian honours for his work.

McCoy died on 13 May 1899. His wife, Anna Maria, whom he had married in Dublin in 1843, passed in 1886. Their children, Frederick Henry and Emily Mary, passed in 1887 and 1891 respectively.

References:

Australian Dictionary of Biography.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Localities

-

Authors

-

Article types