COLLECTIONS REPRESENTING DISABILITY AT MUSEUM VICTORIA

As of January 2010, Museum Victoria holds nearly 800 identified objects, object parts and images representing the lives of the disabled in our society. (Of these, 186 are identified under various forms of the subject 'disability'.) This excludes a large number of additional objects and images relating to medical treatment of both the temporarily and permanently disabled, including psychiatric conditions.

A substantial part of the psychiatric collection was gathered by Dr Charles Brothers, one of the three founding members of the Mental Hygiene Authority, established in 1952. Dr Brothers collected objects and furnishings from psychiatric institutions as he conducted his reforming work. His collection appears to have been motivated by antiquarian rather than political interests.

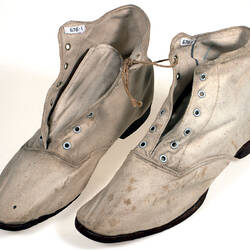

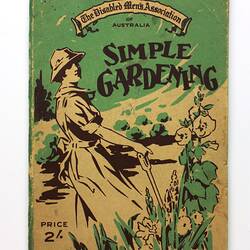

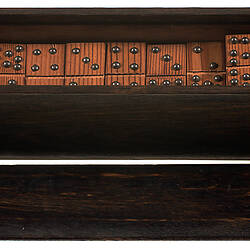

The collection includes a broad range of objects from daily life within psychiatric institutions, including food preparation and consumption, clothing, laundering, sewing, gardening, harvesting and cleaning. These show, as Elizabeth Willis points out, 'the extent to which the larger institutions were run as nearly self-supporting economies'. The confining physical environment is represented through locks, padlocks, keys and passes. Recreation and therapies (as well as a broad range of treatments) are also included in the collection.

The collection was eventually displayed in the Charles Brothers Museum at the behest of Dr E. Cunningham Dax, Chairman of the Mental Hygiene Authority, and was displayed for many years at the Melbourne Health Library in Melbourne.

The collection was transferred to Museum Victoria in 1986, when the Department of Mental Health no longer had the capacity to maintain it. Since then, the History and Technology Department at Museum Victoria has acquired further material documenting life at psychiatric facilities at Sunbury and Beechworth, and from advocacy groups. By 2005 the entire psychiatric collection included approximately 1100 objects (988 were identified in 2010 with the collection name Psychiatric Services), focussing on the period 1848-1950.

The collection highlights the gap between policy and practice, confirmed by Royal Commissions and government enquiries, and illustrated through photographs. Three large 'lunatic asylums' were opened in Victoria in the period between 1867 and 1872: at Beechworth, Ararat and Kew. They were designed to accommodate 400-600 residents. It was hoped that their controlled environments would bring order to the disturbed or chaotic mind. This represented a break from the earlier approach of the Yarra Bend Asylum, characterized by prison-like incarceration. Unfortunately, conditions within the new asylums rapidly deteriorated, due to overcrowding and lack of staff. Patients with very different disorders were housed together, such as violent patients with those with intellectual disabilities. Ultimately, conditions were still prison-like, with patients were kept under lock and key, observation always possible and privacy almost non-existent. An underlying culture of violence and intimidation is suggested though objects such as a cudgel made (probably by a warder) from a piece of rubber hose.

Curative treatments also reflected a gap between theory and practice. The ratio of doctors to patients - some 14 doctors for 5000 asylum patients at one stage - precluded effective individual treatment. The lack of psychiatric medications (later decades would see a dramatic increase in this area) also hindered treatment.

Work undertaken by patients and staff further reflects the gap between theory and practice. This work was supposed to contribute to the asylum economy, covering some running costs though activities such as food production and use of patient labour. However, poor-quality equipment and lack of effective management of resources meant that opportunities were neglected or not maximized.

The objects in the psychiatric collection 'suggest despair, poverty, ignorance or official neglect or indifference', writes Willis. 'However, if we choose to look, we can see evidence of some humanity within the system, some resistance to official oppression and some creative adaptation to poor conditions. There are hints of endurance, bravery and compassion here, even in the midst of squalor and neglect'.

Museum Victoria's disability-related collections also include 123 objects from the Royal Victorian Institute for the Blind (RVIB), acquired in the early 1990s. This collection includes taped books, Braille boards, tools used by visually impaired workers, games and badges.

References:

Elizabeth Willis, 'Home But Away: Material Evidence of Living in Victorian Asylums, 1850-1950', Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, vol.2, no.2, Nov 1995, pp. 111-116.

Elizabeth Willis and Karen Twigg, Behind Closed Doors: a Catalogue of Artefacts from Victorian Psychiatric Institutions Held at the Museum of Victoria, Museum of Victoria, 1994

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Localities

-

Authors

-

Article types