The Tjitjingalla ceremony is one of the most thoroughly documented Aboriginal public performances or 'corroborrees' ever recorded in Australia.

In 1894 the ethnographer Walter Edmund Roth heard about a public dance and song performance called the 'Molong-go' that had been shared by the Wakaya people from the upper reaches of the Georgina River in the Northern Territory with the Pitta Pitta people in outback Queensland. Fascinated to hear that the dance had 'originated from a point east or south-east of Darwin' - some hundreds of kilometres from the Queensland desert country where he was stationed - Roth eagerly documented the dance and its body paint designs.

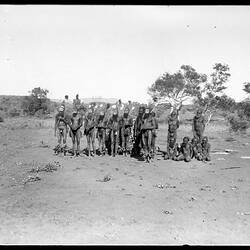

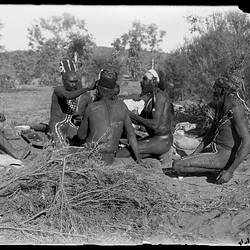

Two years later in 1898 in Alice Springs, Special Magistrate F.J. Gillen wrote to his friend and collaborator in anthropological studies, the then Professor of Biology at the University of Melbourne Walter Baldwin Spencer, explaining that a corroboree almost identical to the one seen by Roth had appeared in Alice Springs. Gillen explained to Spencer that the dance, known as the Tjitjingalla 'corroboree' to the local Arrernte people, had been 'brought down' into the region by a 'northern group'. After attending the performance, which extended over five nights, Gillen reported that the repertoire had indeed originated 1500kms north, in the 'country of the Salt water' and that 'the implements carried by the performers' were 'in all cases the same as described by Roth'. Three years later, during the Spencer and Gillen Expedition of 1901 Spencer collected two of the dancing sticks used in the performance and recorded the song verses on an Edison wax cylinder recorder. A few weeks later when the expedition reached Alice Springs Spencer spent considerable time photographing and filming the dance using his Warwick motion film camera. The sound and film recordings made of the Tjitjingalla are some of the earliest ever made on the Australian continent. On April 30th in Alice Springs Spencer wrote:

'Evening finishing off Tchichnigalla. Latter belongs to Unjiamba [corkwood nectar] group hence designs painted on backs of men are of this totem. Wurly built = Wah-patilla inhabited in Alcheringa [dreaming] by man of Saltwater country, whose name was Chilicherpa. He lived quite alone & walked about looking for his tucker & on returning one day found that a strange mob had assembled near to his wurley. He objected to anyone coming & tried to spear them. They wanted to capture but not kill him & wanted to stay with them & to induce him to do so burnt his wurley. This represented in final scene in which man decorated with undatha [birds down] & armed with a long spear danced. Finally women ordered away & wurley burnt down now belongs to group of Arunta who received it from the Ilpirra'.

In the 1960's two Arrernte men, Bob Rubuntja and Tom Bagot Injola, told T.G.H. Strehlow that this performance had come in to their region via Tennant Creek and then handed on to people in south western Queensland, Peake and Oodnadatta in South Australia and on to Port Augusta. Apparently, it made its way back into the Northern Territory in the 1920s where it was again recorded by anthropologists.

References

Gibson, Jason. "Central Australian Songs: A History and Reinterpretation of Their Distribution through the Earliest Recordings." Oceania 85, no. 2 (2015): 165-82.

Hercus, Luise A. "'How We Danced the Mudlunga': Memories of 1901 and 1902." Aboriginal History 4 (1980).

Kimber, R. G. "Mulunga Old Mulunga. 'Good Corroboree,' They Reckon." In Language and History: Essays in Honour of Luise A. Hercus, edited by Peter Austin, R. M. W. Dixon, Tom Dutton, and Isobel White, 175-91. Pacific Lingusitics Series C 116. Canberra: Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, 1990.

Mulvaney, D.J. "'The Chain of Connection': The Material Evidence'." In Tribes and Boundaries in Australia, edited by Nicholas Peterson, 72-94. Canberra: AIAS, 1976.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types