Summary

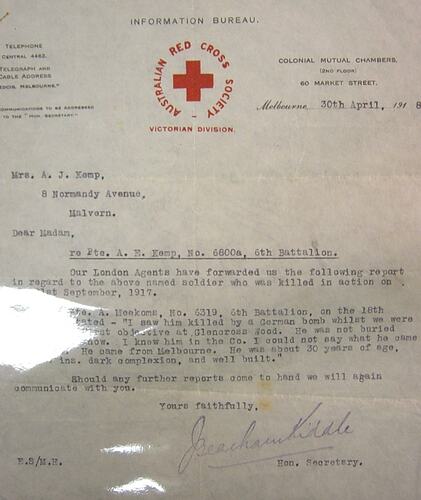

Single-page letter dated 30 April 1918 from the Australian Red Cross, Victorian Division, to the widow of Private Albert Edward Kemp, who was killed in action in Belgium in 1917. It includes Private A. Meekoms' account of Kemp's death:

'I saw him killed by a German bomb whilst we were holding our first objective at Glencross [ie Glencorse] Wood. He was not buried as far as I know. I knew him in the Co. I could not say what he came over with. He came from Melbourne. He was about 30 years of age, 5ft. 7ins. dark complexion, and well built.'

Albert Edward Kemp was a 32-year-old butcher living in Caulfield and married to Annie Josephine, when he enlisted. He and Annie had a daughter, Ethel Mavis, and a baby son, George Percival. Albert enlisted at Royal Park on 4 October 1916, and was assigned to the 22nd Reinforcements, 6th Battalion - regimental number 6800. His battalion left Melbourne 25 October 1916 - just 21 days after he enlisted. He was shipped to France on 27 March and was taken on strength on 4 April. On 21 September 1917, Albert died in the trenches in Glencorse Wood, Belgium. His body was never found. He is commemorated at 29 The Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial, Belgium.

Physical Description

Single page letter, typed on Australian Red Cross (Victorian Division) letterhead, whose insignia red cross is printed in red at centre top.

Significance

The Information Bureau of the Australian Red Cross was often approached by families hoping for news of loved ones missing or wounded in action, confirmation of death or details of how a death occured. This letter was sent from the Australian Red Cross office in Colonial Mutual Chambers, Market Street, Melbourne (now demolished), and it documents the link to the Red Cross's London office, which has forwarded a report.

According to the Australian War Memorial, the Australian Red Cross (ARC) Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau was set up in Cairo in 1915 and moved to Victoria St, London, in May 1916. The War Memorial writes: 'Employing agents to operate in Britain as well as in France and Belgium, official lists of the wounded and missing were scoured, letters written to men on active service, and where possible, comrades of missing soldiers were interviewed in camps and hospitals. Altogether 400,000 responses were sent back to those who placed enquiries with the Bureau. Where a death apparently occurred, the Red Cross staff tried to remove all doubt. Often letters back to families quoted reports verbatim from researchers; the language used in the reports was often unsanitised, from straight-talking soldiers and the descriptions sometimes quite graphic. Reports from various soldiers could be wildly contradictory or clearly wrong, but they were still passed on so that families would have as much information as possible.' -Red Cross Records from the First World War', AWM, 16 March 2009.

More Information

-

Collection Names

-

Collecting Areas

-

Acquisition Information

Purchase from Mr Jeff Kemp, 07 Dec 2006

-

Organisation Named

Australian Red Cross Society, Market Street, Melbourne, Greater Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 1918

-

Person Named

Private Albert E. Kemp - 6th Battalion, Australian Imperial Force (AIF)

-

Inscriptions

Text: INFORMATION BUREAU./AUSTRALIAN RED CROSS SOCIETY/VICTORIAN DIVISION/Mrs. A.J. Kemp,/8 Normandy Avenue/Malvern/Dear Madam,/re Pte. A.E. Kemp, No. 6800a, 6th Battalion./Our London Agents have forwarded us the following report/in regard to the above named soldier who was killed in action on/the /Pte. A. Meekoms, No. 6319, 6th Battalion, on the 18th/February stated - "I saw him killed by a German bomb whilst we were/holding our first objective at Glencross [ie Glencorse] Wood. He was not buried/as far as I know. I knew him in the Co. I could not say what he came/over with. He came from Melbourne. He was about 30 years of age,/5ft. 7ins. dark complexion, and well built."/Should any further reports come to hand we will again/communicate with you. The letter is signed by Beacham Kiddle, Hon Secretary.

-

Classification

-

Category

-

Discipline

-

Type of item

-

Overall Dimensions

202 mm (Width), 252 mm (Height)

-

References

Information about the Australian Red cross from AWM web site [Link 1] accessed 23/4/2009.

[Book] Hutchinson, Garrie. 2009. Remember Them; a Guide to Victoria's Wartime Heritage., 30-2 Pages

-

Keywords

Death & Mourning, Wars & Conflicts, World War I, 1914-1918, Making History - Kemp Mourning Collection