Summary

Alternative Name(s): Autograph Album

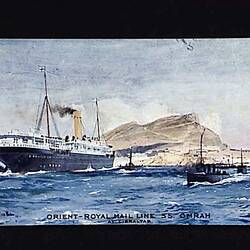

World War I period autograph book with gilt edged pages and floral cloth covers, with dated entries on every page, together with war-related ink sketches and a watercolour. Containing many entries from AIF member and several entries made on a voyage of the ship RMS Omrah, the album reflects one of the ways soldiers memorialized their experiences of war. (RMS stands for Royal Mail Ship or Royal Mail Steamer.)

The autograph book most likely belonged to Elizabeth Louisa Shelly (nee Floyd), who brought it with her on her journey to England on the RMS Omrah in September-October 1916. Her husband, Edmund 'Ned' Shelly, had been posted to Egypt, then England, as a soldier. Edmund served as a cook at the No 2 Command Depot in Weymouth. The album contains entries made by several members of the Shelly family, both in Australia and serving overseas. The album also contains entries from other soldiers serving with the No 2 Command Depot in Weymouth as well as local civilians.

The Omrah was built in 1899 and served as a passenger ship before being refitted as a troopship by the Admiralty for service in World War I. It was part of the convoy the carried the first contingent to Egypt, departing in September 1914; Commonwealth control of Omrah ceased on 2 October 1915 (some sources say 10 Feb 1915). It was then given back to its owners, the Orient Line (according to image caption 00040957 in the National Library). In January 1917 it was again used to take Australian soldiers to war. It was sunk in the Mediterranean on 12 May 1918, with the loss of one life.

One entry features a colour drawing of a soldier walking out a door, with the inscription 'Goodbye; Maybe forever'. It is signed Sidney R. Dudley. Some signatures are in French.

Physical Description

Autograph book, hard cover, covered with green cloth and decorated with purple flower with green foliage. The pages are variously blue, pink and white, with gold on edges of paper, visible only when album is closed. Marbled paper lines the front and back of the album. One entry is in French and there is another short entry in Spanish. The album includes a leaf inscribed in pen 'T. OCONNOR'. Illustrations include a coloured line drawing of a bird on a 'fish cake', inscribed 'Quoth the Raven / Never more!'; and, drawn by a skilled artist, a man in a top hat pushing a pram-full of assorted goods and a baby, with the inscription 'FAR-REACHING EFFECT OF THE PUSH'. Near the back, a powerful ink drawing of two soldiers is inscribed 'Zero Hour, at / the Front, 1916'. The cover has come adrift of the spine.

Significance

Statement of Significance

The album is historically-significant because it documents personal voices from World War I in the form of poems, witticisms, well wishes and drawings. It provides insights into the thoughts of people at home (both in Australia and England), front-line soldiers (especially W. Martens' entry) and the experiences of soldiers serving in non-combat roles such as depots (especially Edmund Shelly's poem). In particular, it apparently documents the experience of a woman, Elizabeth Louisa 'Louie' Shelly, who sailed to England to be with her husband during his war service - a little-documented phenomenon, particularly for people who travelled third class on the voyage.

The album links outward to myriad personal stories, some not hinted in its pages. For instance, both her husband and his brother appear to have contracted gonorrhoea in Egypt. Her husband's penis received a gunshot wound not long before he was diagnosed - perhaps a related event. (Peter Stanley's book Bad Characters (2010) discusses both venereal diseases and self-inflicted wounds.) They were repeatedly treated for the remainder of the war. The album's author and her husband never had children. His brother faced other difficulties too, rebelling against the restricted life of the soldier and ending the war with a 10-year penal servitude sentence for desertion (of which he served only two years in England).

Many other soldiers are named in the album, at least one of them later to die in the war. It has been possible to piece together the World War I-era provenance using archival sources such as newspapers and war records held in the National Archives. However, there is a gap in the provenance from 1920 till the object came to Museum Victoria in 2010 - it was acquired through auction.

More Information

-

Collecting Areas

-

Acquisition Information

Purchase

-

Ship Depicted

-

Date Made

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Person Named

-

Inscriptions

On cover: 'Autographs'. Various other inscriptions - autographed throughout.

-

Classification

-

Category

-

Discipline

-

Type of item

-

Overall Dimensions

174 mm (Width), 14 mm (Depth), 142 mm (Height)

-

References

Information on the World War I service of Ernest Samuel Hazeldine from National Archives, barcode 4749247, accessed 15 Nov 2010. Information on the Omrah from [Link 1] [Link 2] [Link 3]

-

Keywords

Defence Forces, Postal Services, Racism, World War I Fundraising, World War I, 1914-1918, Making History - War Diaries and Correspondence, Making History - War Diaries and Correspondence