Summary

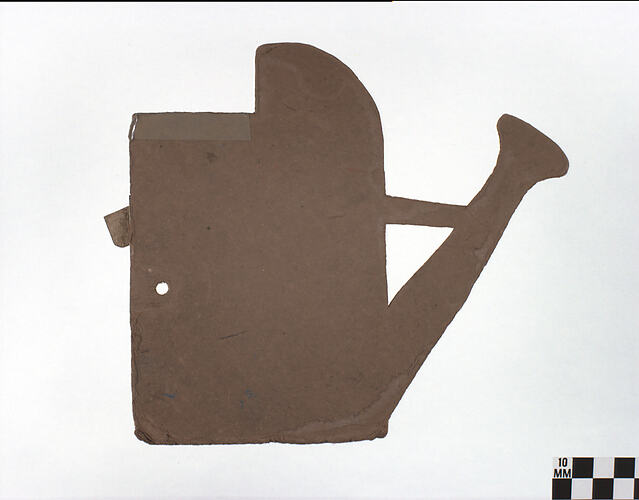

Alternative Name(s): Katavrechtiri

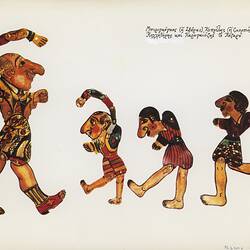

This watering can was made in the 1960s by the Greek puppeteer and popular artist Abraam (Antonakos) in his Athens workshop, and used in performances in Greece during the 1960s. This and most of the puppets in the collection were brought to Australia by Abraam Antonakas for his performances at the Astor Theatre in Melbourne in 1977. He then left the collection with Dimitri Katsoulis who used them in all his subsequent performances in Victoria and in South Australia from 1978 to 1991.Dimitri Katsoulis migrated to Australia in 1974 to escape a regime that repressed Greek artists. He had trained in Greece with theatre and film companies as an actor and technician. A master of the traditional Greek shadow puppet theatre, his performances explored contemporary issues such as the isolation of migrant women and children. Unable to obtain funding and support, he returned to Greece in 1991, leaving his entire collection to the people of Victoria. It includes 32 shadow puppets and around 170 props, set backdrops and technical tools and stage equipment. Dimitri has since returned to Melbourne and assists the Museum to continue to document this rich art form within both local and international contexts.

The watering can was attached to the hand of Karaghiozis, a character in the centuries-old Greek Shadow Puppet Theatre (Karaghiozis) tradition. It was used by Karaghiozis in all the comedies whenever he beat up one of the other characters in a play. In the comic play 'Karaghiozis the Servant', Karaghiozis is holding a watering can and uses it to beat up the prospective suitors that old man Stavridis has notified to come to his house to meet his daughter. Eleni bribes the servant Karaghiozis to beat up and chase away the prospective suitors that come and say that they like her. She has arranged with Karaghiozis that when she tells each suitor to go outside and wait for the betrothal, Karaghiozis will go out and give them a beating instead of the engagement ring they were expecting. In the play, 'Megas Alexandros [Alexander the Great] and the Cursed Snake', when the snake had grabbed Alexander the Great by the head, he calls out to Karaghiozis for help. He slapped it a few times with his hand, however the snake did not subside. Then Karaghiozis enters his shack and yells out 'Quick Kolitiris, give me the watering can.' Karaghiozis emerges with watering can in hand and starts hitting the snake about the head with it. The snake retreats from pain, Alexander the Great is freed and continues fighting the snake, having regained his courage after being inspired by Karaghiozis, and he manages to kill the snake. He thanks Karaghiozis for his assistance.

Information supplied by Greek Shadow Puppet Theatre master Dimitri Katsoulis, 2007.

Physical Description

A piece of thick brown cardboard cut in a watering can shape. It has a container and spout, but no handle. On one face the original sketch marks, in ballpoint, are visible. A piece of red and white paper has been attached to the same face using brown packing tape. A hole has been cut on one side to attach a supporting rod.

Significance

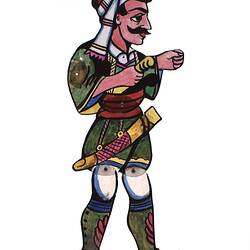

This collection of puppets, props, stage sets, and technical tools and equipment relating to traditional Greek Shadow Puppet Theatre is unique in Australia and rare in international public collections. The history of Greek Shadow Puppet Theatre, its puppet characters and the methodology of its performance has been recorded in partnership with the puppet master to whom the collection belonged. The collection is highly significant both as documentation of an important cross-cultural, centuries-old art form, and as an example of the transnational migration of cultural activity between Greece and Australia. It is a collection which was created and performed in Greece and Australia from the mid to late twentieth century, by two puppet masters, who transported the tradition between two countries. Abraam Antonakos came to Australia in 1977 to perform the puppet theatre and then deposited the puppets with Dimitri Katsoulis, who had migrated to Australia in 1974. Dimitri's story becomes one of migration experience, cultural maintenance and adaptation, and finally return migration and the discontinuance of this cultural art form in Australia.

More Information

-

Collection Names

-

Collecting Areas

-

Acquisition Information

Purchase

-

Artist

-

User

Mr Abraam Antonakos, Athens, Greece, 1960-1977

Abraam made the puppet in Greece, and used it in performances during the 1960s and 1970s; and then in Victoria in 1977. -

User

Mr Abraam Antonakos, Melbourne, Greater Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 1977

Abraam made the accesory in Greece, and used it in performances during the 1960s and 1970s; and then in Victoria in 1977. -

User

Mr Dimitri Katsoulis, Australia, 1978-1991

Dimitri was given the puppet by Abraam in 1977 and then used it in his performances in Australia until 1991. -

Inscriptions

On one face, l.l., in ballpoint ink, "16-2-6/ABPAA/AI". On paper, in pencil, "44c".

-

Classification

-

Category

-

Discipline

-

Type of item

-

Overall Dimensions

20.5 cm (Length), 18.5 cm (Height)

-

References

[Link 1] Malkin, Michael, R. Traditional and Folk Puppets of the World, A.S. Barnes & Co., Inc., N.J., 1977; Simmen, Rene, The World of Puppets, Elsevier, Phaidon, London, 1975; Hogarth, Ann & Bussell, Jan, Fanfare for Puppets!, David & Charles Publishers Ltd, USA, 1985; Yayannos, A & Ar and Dingli, J. The World of Karaghiozis, 1976

-

Keywords

Cultural Maintenance, Greek Communities, Greek Immigration, Karaghiozis Theatre, Shadow Puppetry, Theatres, Working Life