Summary

An account of patient personal hygiene and hygiene facilities provided for patients in psychiatric hospitals in Victoria Australia from 1886 to 1970.

In 1886 Dr Samuel Brierley of the Beechworth Lunatic Asylum told an official inquiry that much of the clothing patients wore at his institution should be condemned, as it was so filthy (Report of the Royal Commission on Asylums for the Insane and Inebriate, 1886, Minutes of Evidence Q.11675, p.505, and Q.11692-11693, p.506). He also noted that there was such a shortage of towels on the weekly bath-day that several patients at a time were dried with the same bed sheet which had been used as bedding during the week (Report of the Royal Commission on Asylums for the Insane and Inebriate, 1886, Minutes of Evidence Q.11695-11702, p.506).

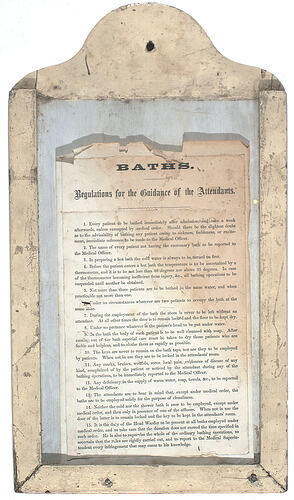

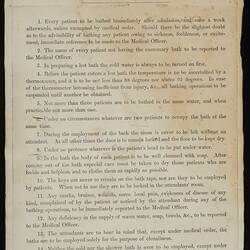

The inquiry responded that this 'scandalous and reprehensible' practice had been condemned years earlier, but was still tolerated in some institutions though decidedly 'unwholesome' (Report of the Royal Commission on Asylums for the Insane and Inebriate, 1886, p.xlvi). As this comment implied, there were strict rules for the bathing of patients, covering frequency and temperature of baths, bathing supplies including towels, and supervision (Report of the Royal Commission on Asylums for the Insane and Inebriate 'Regulations for Baths', 1886, pp.cv-cvi). Another unhygienic circumstance that Brierley reported on was the total absence of toilet paper in the latrine blocks (Report of the Royal Commission on Asylums for the Insane and Inebriate, 1886, Minutes of Evidence Q.11705-11712, pp.506-7).

Beechworth Asylum was not alone among Victorian mental health facilities to be criticised for its poor hygiene and dubious bathing practices. As early as 1864, reports circulated that there was 'only a single latrine provided with water in the whole three-quarters of a mile over which the buildings of the Yarra Bend asylum are scattered' (Hospitals and Lunatic Asylums, 1864, p.12).

Kew Asylum also came in for criticism in 1903 when Dr Stanley Argyle, a medical practitioner and mayor of Kew, told the Victorian Premier about the degrading bathing experience of some women patients:

Forty patients were brought together into a corridor, the windows of which had no blinds, and only sheets pinned across them. They were undressed together, and walked naked through the scullery, where the meals were being prepared, to the bath. After they had been bathed they were walked back, naked and dripping wet, to the corridor (Anon, 1903, p.13).

While issues relating to bathing decorum re-surfaced over time, a concerted effort to improve hygiene commenced in 1905 with the appointment of the first departmental pathologist, Dr John Mackeddie. He and his successors used the emerging tools of bacteriology to investigate disease outbreaks and recommended solutions. An early breakthrough was the direct tracing of a typhoid epidemic to unsanitary human waste collection systems, unsatisfactory laundering practices and the presence of disease carriers (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1907, pp. 29-32; Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1908, p. 28).

However, lethal disease outbreaks continued to occur. The great influenza pandemic of 1918-19 claimed 68 lives, with Yarra Bend Asylum the most severely hit. Fortunately the disease took hold in different mental health facilities at different times, limiting the impact of the crisis (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1919, p. 20).

Asylum dysentery (ulcerative colitis) was an ongoing concern and, in a major epidemic from 1933 to 1935, hundreds of patients across the mental hospital system developed the highly infectious condition most probably due to faulty sewage systems. In 1935, the department pathologist, Dr Clive Farran-Ridge, attributed the deaths of 45 Mont Park Mental Hospital patients and 42 Kew Mental Hospital patients wholly or partly to dysentery (Report of the Director of Mental Hygiene 1936, p. 24). The construction of isolation blocks and improvements in sewage systems to markedly reduced deaths from dysentery.

Delays in rectifying hygiene problems were stifled due to a complex process for gaining building works approval. In 1967, Ward M12 of the Kew Mental Hospital reportedly had a 'disgraceful' ablution situation with 55 male patients and additional staff members sharing two toilets and two showers in a dilapidated bathroom. The first requisition to alter the block had been placed around 1951 and, despite repeated complaints, conditions remained appalling some sixteen years later (Minutes of the Advisory Committee to the Mental Health Authority, 1967, p.2). Similarly, in the early 1970s, Medical Superintendent Dr John Fordyce rejoiced in a small victory when he finally managed to get covers placed over drains outside a ward housing incontinent patients at Beechworth Mental Hospital, more than 60 years after the first recommendation that they be covered (Fordyce, 1977, p.1)!

In November 1970, the foul odour of the toilet block at the Ararat Mental Hospital was causing concern in spite of frequent deodorant spraying. Deodorant tablets were unsafe as some patients had attempted to eat them (Minutes of the Advisory Committee to the Mental Health Authority, 14-16 November 1970, p.2). However, the use of deodorants and antiseptics raised other issues according to social worker, Mr A S Colliver, who found it 'quite depressing to be met by the strong smells of antiseptic every time a visit is made to an elderly person' (Colliver, 1966, p.4). Since such overpowering institutional smells 'could well influence the emotional climate' in which visits by families, friends and staff took place, he advocated filling wards with 'the smell of mown grass, the aroma of home cooking, and the scent of stocks and wisteria', thus reminding patients of their earlier lives.

References

Anon, 'Care of the Insane. Victoria's Obsolete Methods. Important Deputation. The Need of Reform' (1903) Argus, 1 August, p. 13

Colliver, A.S. (30 November 1966) 'Accommodation for the frail aged - some factors on its provision', Address to a meeting of the Old People's Welfare Council of Victoria, State Library of Victoria Mental Health Auxiliaries Collection, Box 5/13, p.4

Farran-Ridge, C (1936) Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane for 1935, Victorian Parliamentary Papers, vol 1, p.24

Fordyce, J (18 January 1977), letter to Pardy, E, State Library of Victoria Mental Health Auxiliaries Collection, Box 3/13, p.1

Hospitals and Lunatic Asylums (1864-65), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, vol 3, p.12

Minutes of the 282nd meeting of the Advisory Committee to the Mental Health Authority (18 July 1967), State Library of Victoria Mental Health Auxiliaries Collection, Box 4/13, p. 2

Minutes of the347th meeting of the Advisory Committee to the Mental Health Authority (14-16 November 1970), State Library of Victoria Mental Health Auxiliaries Collection, Box 4/13, p.2

Report of the Royal Commission on Asylums for the Insane and Inebriate, Victoria (1886), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, vol 2

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1907 (1908), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, vol 1, pp.29-32

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1908 (1909), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, vol 2, session 2, p.28

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1919 (1921), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, session 1, p.20

Report of the Director of Mental Hygiene 1936 (1937), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, session 2, p.24

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types