Summary

An account of the dental hygiene of patients at psychiatric hospitals from Victoria Australia from 1908 to 1958.

On 10 December 1908, Mr. Dwyer, the father of a patient at Yarra Bend Asylum, wrote to the Chief Secretary (the Minister responsible for the Hospitals for the Insane) to express his concern at 'the complete neglect of the teeth of the Patients'. There was no question, he declared, that the 'dental caries and malformations' that resulted caused them 'much suffering' (Dwyer, 1908a). Five days later, he wrote again, suggesting that pending the appointment of a dentist the patient's teeth might be preserved if instructions were issued for their 'daily cleansing with an antiseptic liquid'. To support his suggestion, he quoted from an opinion he had obtained from a 'well known City Doctor' who declared that there could be no dispute about 'the need for dentistry among the Patients. At the root of the whole difficulty is the desire to put the Insane out of sight & forget them' (Dwyer, 1908b).

Dwyer was clearly anxious to see something done because two days later he wrote a third time. He had that very morning met with the Superintendent of the Dental Hospital, having arranged for the latter to examine the teeth of a patient at Yarra Bend. The report makes for painful reading: 'I found the Patient's teeth in an advanced state of caries [decay], and of the eight teeth which I extracted, abscesses had formed under three of them & the mouth of teeth showed a shocking & disgraceful state of neglect' (Dwyer, 1908c).

Asked for comment on the letters, the Inspector-General of the Insane, Dr W Ernest Jones, explained that:

Consulting (Honorary) dentists have been appointed to the Hospitals for the Insane in the past - They are practically useless - no good work is honorary in institutions. At present the medical officers have full power to deal with the teeth of patients suffering from dental caries in various ways. One being (if the patient can afford it) to call a dentist in to do the necessary work & another method to take the patient to the Dental Hospital. No request for a consultant dentist has ever been refused & if there has been any neglect in the matter, it is entirely the fault of the medical officer (Jones, no date).

Extraction performed by the medical officers evidently constituted the extent of dental care unless a patient could afford private treatment and was able to request it or had an advocate like Dwyer to do so on their behalf. It seems there was no systematic provision for dental treatment and little apparent willingness to act.

The only response Dwyer received was a letter to the effect that patients requiring dental care were sent to the Dental Hospital, a fact he had personally heard contradicted by its Superintendent, who told him that 'only an odd case was sent to the Dental Hospital & only then when any treatment beyond extraction was impossible' (PROV, VPRS 3992/P, Unit 1105, File 1908/ D8867, file notations, 16 and 18 December 1908 and Dwyer, 1908c).

However, his campaign seems to have been a catalyst to attempt to remedy the neglect of dental care. In 1909, the General Estimates included provision for a visiting dentist but none was appointed (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1909, p.47 and 1910, p.50). As an apparent alternative, in the next few years more patients were sent to the Dental Hospital, where the cost of providing many of them with 'artificial teeth' was met by the Lunacy Department (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1914, p.31; 1916, p. 20; 1917, p. 21).

In 1918, however, the Inspector-General urged the government to authorize the appointment of a dentist to work in the hospitals on therapeutic grounds. There was, he asserted, 'unquestionably good reason to believe that the toxæma [blood poisoning caused local bacterial infection] resulting from diseased conditions of the mouth is quite sufficient to retard or even prevent recovery of a patient suffering from what would otherwise be a curable mental affection'. Nor, he added, was there any good reason to allow even incurable patients 'to become gradually edentulous', implying that this was exactly what was happening (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1917, p.39).

Jones returned to this argument in 1922, when he again drew the attention of the government to the need for a dentist. Sending patients to the Dental Hospital was, he declared, 'wholly inadequate, and only enables a very small number of the patients requiring dental attention being dealt with'. He believed these circumstances must diminish the likelihood of mental recovery, it being 'conceivable that many cases of mental disorder are inhibited by the fact that their teeth are in a bad state, thereby causing an extent of ill-health which must necessarily veto their chances of mental recovery' (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1921, p.24; for the context for these ideas see Scull, 2005).

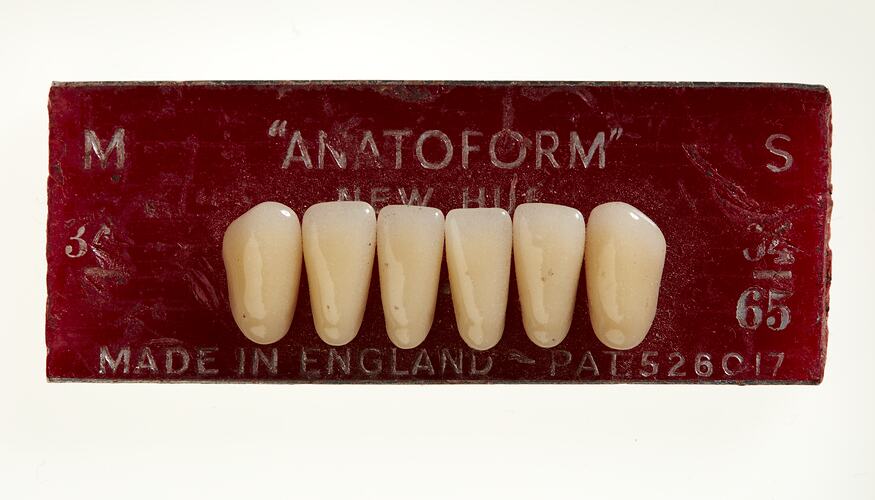

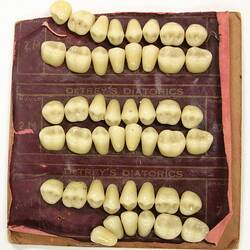

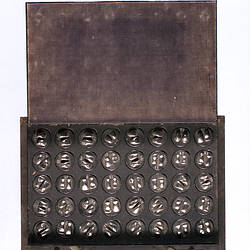

In 1923, the government finally authorized 'the appointment of a full-time qualified dentist to certain of the metropolitan hospitals' (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1923, p.3). Early the following year, Mr. L. P. G. Govett won the post from a large field of candidates. Based at Royal Park, he visited each of the metropolitan institutions at Kew, Sunbury and Mont Park in turn. According to the annual report, his 'work chiefly consisted of extractions, but he was able to undertake fillings for 106 patients, and treatment of pyorrhea [periodontitis] without removal of teeth in 108 cases' (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1924, p.34). In the years that followed, Govett saw literally thousands of patients, performing countless extractions. He also filled patients' teeth, treated their periodontal disease, performed operations under anaesthetic, making and repairing many sets of dentures (For example Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1926, p.30; 1931p.20).

At the conclusion of his first report on Govett's work, the Inspector-General expressed the hope that when he had caught up with the accumulated demand for treatment, 'time will be found for him to undertake a special research into the association of mental diseases with dental defects' (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1924, p.34).

Very occasionally, Govett received assistance from patients with dental expertise. In the last three months of 1927, for example, the help of a patient previously 'employed as a dental mechanic' made it possible to produce 'more artificial dentures' than he otherwise could have. Sadly, the patient's skills were lost to the Clinic when he experienced 'a further mental breakdown' (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1927, p.30). Twelve years later, 'the assistance of a dentist - an L. D. S. England - who was a voluntary boarder at Royal Park' saw the dental laboratory increase its production 'of new dentures.by approximately 30 per cent'. However, except for this patient labour he was still without an assistant, despite repeated requests (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1939, p.35). Inmates at Ararat, Beechworth and Ballarat Mental Hospitals received 'no systematic treatment by a qualified dentist' well into the 1940s, despite frequent requests (Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1939, p.35).

A second Dental Clinic opened at Mont Park Mental Hospital, under the direction of Mr A. Coppin (Report of the Director of Mental Hygiene 1943, p.24). By 1948, the Department employed 'two whole-time dentists, two dental mechanics, and two dental nurses' and only at Beechworth was 'there no permanent arrangement for dental treatment' (Mental Hospitals' Inquiry Committee 1948, p.19). A decade later, Govett retired after thirty-four years service, and was replaced by Mr Frank H. Burrage, B.D.Sc, L.D.S. Patients in both the metropolitan and country hospitals finally had access to dental care, either from the Mental Hygiene Authority dentists or from visiting practitioners (Report of the Mental Hygiene Authority for 1958 , pp.47, 60, 64, 72, 77, 81, 82).

References

Dwyer (1908a) to the Chief Secretary, 10 December, PROV, VPRS 3992/P, Unit 1105, File 1908/ D8867,

Dwyer (1908b) to the Chief Secretary, 15 December, PROV, VPRS 3992/P, Unit 1105, File 1908/ D8867.

Dwyer (1908c) to the Chief Secretary, 17 December, PROV, VPRS 3992/P, Unit 1105, File 1908/ D8867.

Jones, W Ernest to the Under Secretary, (no date) PROV, VPRS 3992/P, Unit 1105, File 1908/ D8867.

Mental Hospitals' Inquiry Committee (March 1948), Report on the Department of Mental Hygiene, Its Hospitals, and Its Administration, Melbourne, Government Printer.

PROV, VPRS 3992/P, Unit 1105, File 1908/ D8867, file notations, 16 and 18 December 1908.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1909, (1910), Victorian Parliamentary Papers Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1910 (1911), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane, 1914 (1915) Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1916 (1917), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1917 (1918), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1921 (1923-4), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1923 (1925), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1924 (1925), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1926 (1927), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1927 (1928), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Report of the Inspector General of the Insane 1931 (1932), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, second session.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1937 (1938), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. I.

Report of the Director of Mental Hygiene 1938 (1939), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. I.

Report of the Inspector-General of the Insane 1939 (1940), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. I.

Report of the Director of Mental Hygiene 1943 (1944-5), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. I.

Report of the Mental Hygiene Authority for 1958 (1959-60), Victorian Parliamentary Papers, Vol. II.

Scull, Andrew (2005), Madhouse: A Tragic Tale of Megalomania and Modern Medicine, New Haven, Yale University Press.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types