MALLEE FOWL

Lipoa Ocellata, Gould - (477)

Geographical Distribution - New South Wales, Victoria, south and West Australia.

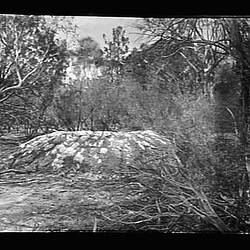

Nest - A large conical-shaped heap or mound of sand, &c., covering a bed of leaves and other vegetable debris about eight inches in thickness; usually situated in a water track in the dense scrub of sandy tracts, or in reddish ironstone gravel country, such as the Mallee (so names from a species of dwarf eucalyptus which grows there), &c. Dimensions, 10 to 12 feet in diameter at base, or a circum-ference 30 to 40 feet, and height 2 yo 4 feet.

Eggs - Clutch, twelve to eighteen - other authors seven to eight; long oval in shape or elliptically inclined; texture coarse but shell exceedingly thin; surface without gloss; colour, when first laid, light-pink or pinkish-buff, which on being scratched or removed shows a yellowish-buff ground; this in turn, as incubation proceeds, chip off in patches and reveals a whitish shell. Dimensions in inches of four eggs from the same mound: (1) 3.73 x 2.35, (2) 3.7 x 2.42, (3) 3.52 x 2.26, (4) 3.44 x 2.26. (Plate 18.)

Observations - The mound-raising birds are the ornithological curiosities not only of Australia but of the world.

This remarkable and truly solitary Lipoa dwells in the drier and more arid scrubs of Southern Australia generally, being particularly partial to the Mallee (a dwarf species of eucalypt) tracts, hence the vernacular title Mallee Hen.

The Lipoa resembles very much in shape and size a greyish-mottled domestic Turkey, but is slightly smaller, more compact, and stouter in the legs. It has no wattles about its head, but has a small tuft of feathers falling gracefully back from the crown.

In Western Australia the Lipoa has its most northerly range apparently just above the tropical line, the Calvert Expedition having found evidences of the bird between Cue and Separation Well, in the Great North-west Desert. Mr. Tom Carter obtained eggs from the natives, gathered between Wooramel and the Murchison River. The furthest point south touched by the Lipoa is, or rather was (for I fear they have been driven out of the locality or destroyed by foxes), the Brisbane Ranges between Bacchus Marsh and the You Yangs, Victoria. At all events, the birds were there during the season 1887, Mr. A. Cameron, a station employé, having seen a nest, apparently just ready for eggs. He also heard of a person who found another nest containing eggs.

What a profound pity these wonderful and most interesting birds could not be properly preserved, because they are undoubtedly fast disappearing! I believe I have the record of the last eggs taken in the immediate neighbourhood of Bendigo. That was the season of 1879. I saw eggs that were obtained from a mound in the Bagshot forest. Formerly the birds were plentiful further north in the Whipstick scrub. During the Whipstick rush (1861) birds were exposed for sale in the poulterers' shops in Bendigo.

The aborigines in the Bendigo district, which are now, like the bird, defunct, called the creature 'Low-an-ee.' Mr. F. R. Godfrey recollects hearing the natives of the Lower Loddon call the bird 'Louan.' The great shire of Lowan, in the Wimmera district, derives its title from the native name of the bird. In Western Australia the Lipoa was first called by the trivial name 'Native Pheasant', but is now usually known by its nave name 'Ngow' or 'Nau'. Gould states other Western tribes called the bird 'Ngoweer' signifying a tuft of feathers.

Decidedly the most peculiar feature in the economy of the Lipoa, or Mallee Hen, is that it does not incubate its eggs in the usual manner, but deposits them in a large mound of sand, where they are hatched by the action of thee sun's rays, together with the heat engendered by the decomposing vegetation placed underneath the sand and eggs. In constructing a new nest or mound, a slight hollow, usually a water track or shallow gully, is selected, in almost impenetrable scrub. The spot is further hollowed or scooped out, and filled with dead leaves and other vegetable matter. Then all is completely enveloped with sand, which is scraped up for several yards around.

About the end of April or the beginning of May both birds (male and female) commence to clear out their old mound or construct a new one, which is then left open until June or July (the late Mr. K. H. Bennett states October)* when leaves, &c., are gathered and placed therein. After the leaves are thoroughly saturated by the winter rains, they are covered up with the sand. The fact that the mound is usually situated in a shallow course or slight gully, further insures the vegetation becoming thoroughly soaked. The female commences to lay in September, or usually October.

Two or three inches of dry loose sand are thrown over the leaves, then tier or layer of four eggs (Gould states eight) is deposited, each placed perpendicularly on the smaller end. The four eggs are in the form of a square, four or five inches apart. An inch or two more sand covers them, and another tier of eggs is placed opposite the interstices of the sub-tier, and so on, till the complement is reached, three or four tiers amounting to between twelve and sixteen eggs. Mr. Charles McLennan, who has enjoyed exceptional experiences with Mallee Hens' mounds, tells me there are always four eggs in the bottom tier, but sometimes six in the other tiers, except the topmost tier, which finishes with one only, the number of tiers being usually three, occasionally four. The centre or portion in the heart of the mound containing the circle of eggs is about fourteen inches in diameter. One of Gould's informants, Sir George Grey, who first mentioned the singular position of the egg, states: - 'When an egg is to be deposited, the top of the mound is laid open, and a hole scraped in its centre, to within two or three inches of the bottom (? Top) of the layer of dead leaves. The egg is placed in the sand just at the edge of the hole, in a vertical position, with the smaller end downwards. The sand is then thrown in again, and the mound left in its original form . . . When a second egg is laid it is deposited in precisely the same plane as the first, but at the opposite side of the hole, before alluded to. When a third egg is laid it is placed in the same plane as the others, but, as it were, at the third corner of a square. When the fourth egg is laid, it is still placed in the same plane, but in the fourth corner of the square, the figure being of this form - : the next four eggs in succession are placed in the interstices, but always in the same plane (?), so at last there is a circle of eight eggs, with several inches of sand intervening between each'.**

In one mound opened by Sir George Grey, which, however, had been previously robbed of several eggs, he found two eggs opposite each other in the same plane, and a third egg four and a-half inches below them, a circumstance which he says 'led me to imagine it was possible that there might be some-times successive circles of eggs in different planes.'

Mr. F. R. Godfrey states:- 'I have more than once seen a second tier of eggs exactly above the lower, but this is a rare occurrence, and sets one puzzling how the birds that are first hatched, which of course occupy the lower story, can get out of their prison without disturbing those immediately above them.'

During laying time an egg is deposited every third day. A great amount of toil devolves upon the hen, assisted by her mate, because they have to dismantle and rebuild a large portion of the mound at the laying of each egg. A mound containing eggs is always left conical shaped in dull or wet weather, but in warm sunny days the top is somewhat hollowed like a miniature extinct volcano, which enables the heat from the sun's rays to concentrate and penetrate the centre among the eggs, therefore when covered up by the owners before sundown, the heat so absorbed is retained for a lengthened period. Mr. C. McLennan says:- 'I have been taking particular notice of them (Mallee Hens), for I love to watch them at work. They have a habit of flattening out their nest about 10 o'clock a.m.., in order to admit the heat of the sun, and about 3 p.m. they build the mound up again.' He never saw more than a pair of birds (male and female) working at the nest.

In building and razing the mounds the birds use their strong fee for scraping, but the loose sand is swept up and impelled forward by the aid of the breast and wings.

The eggs, which are laid between 9 and 10 o'clock in the morning (not at day-break, as stated by one writer), are placed in their perpendicular position by the parent by the aid of its feet, scraping up the sand first on one side, then the other. From the position of the eggs, an as a natural consequence, the chicks are hatched in an upright attitude, their legs drawn up in front, and toes near their back; therefore, it may seem an easy matter when the young are delivered from the shell to wriggle through the running sand, and so free themselves from this great earthen womb. It need no longer be a disputed point whether or not the young are assisted out by their parents.

Sir George Grey (in Gould) states, from information most probably received from the blacks, that 'the young one scratches its way out alone; the mother does not assist it. They usually come out one at a time; occasionally a pair appear together. The mother, who is feeding in the scrub in the vicinity, hears its call and runs to it. She then takes care of the young one as a domestic hen does of its chick. When the young are all hatched, the mother is accompanied by eight or ten young ones, who remain with her until they are more than half-grown.' The last part of this statement is questionable. The young can fly from birth, and probably lead an existence independent of their parents. Mr. Bennett, from careful observations, entertained the belief that the young Mallee Hen can liberate itself from the mound, mentioning that on many occasions, when opening mounds, he has found the chick so near the surface that in a few minutes more it would have effected its escape unaided. Mr. Bennett argues if the chicks by their own exertions could come up from the lower layer to where he had unearthed them, they could certainly have passed through the few inches of loose sand near the top.

Further, the following is conclusive evidence, I think, that the Lipoa chick does liberate itself from the hatching mound. In answer to a direct question of mine, Mr. Charles McLennan, who has had twenty odd years' experience, trapping, &c., in the Mallee, replies: 'There is no doubt that the young ones can get out themselves, for when I was standing near a mound one day I saw a young one come up through the sand, and I have found them very near the top of the mound.' Subsequently, Mr. McLennan wrote: 'I have seen a good many young birds work their way out of the mound lately.'

By way of experiment, Mr. Dudley Le Souëf had a piece of wire netting placed round a mound that con-tained eggs. Result: none of the young emerged, but died in their shells. This may seem to prove that the parents must assist the young out. They probably do so indirectly by visiting the mound occasionally and working at it, thus keeping the soil loose and friable. In the case of the mound wired-in by Mr. Le Souëf, the sand had evidently become set or hardened for want of attention, and thus prevented the escape of the young at the proper time.

With regard to the birds frequently visiting the egg mound to repair damages, &c., Mr. Bennett states:- 'I may mention that on one occasion I opened a nest about 10 o'clock in the morning, which contained three eggs. I took one, as I knew from its delicate colour that it was quite fresh. I left the nest open, and having occasion to repass it about two hours afterwards, I found the bird had in my absence made it up again. Thinking it might be possible that the egg I had taken was not the morning's laying, I again opened the nest, but there were the two eggs only. This time I opened the mound to a much greater extent, drawing the sand back to a considerable distance and again leaving it open. Shortly before sun-down I returned to the nest again and found all damage repaired.'

As previously mentioned, the laying season usually commences about the beginning of September, and extends through the two following months, consequently, as the female approaches the complement of her eggs, in the one mound eggs are found in various stages of incubation. The duration of the period of incubation has not yet been determined. I have hazarded the opinion that it is probably about six weeks (some observers say five)*** for the following reasons: - First, my brother, Mr. W. R. G. Campbell, during his residence in the Mallee country, observed a mound containing thirteen eggs and newly-hatched chicks. Now, as the bird lays two eggs a week (or one every third or fourth day), that would give about six weeks from the time the first egg was laid until the first appearance of young. Second, as some of the later laying birds finish their clutch about the end of November, the last of the young has been observed emerging from mounds about the middle of January.

We have accepted the usual breeding time of the Mallee Hen, from September to January, under normal conditions, but, as Mr. Bennett has pointed out, the laying period is regulated by the character of the season or rains. I believe eggs have been taken in New South Wales in July.

Gilbert, in the Wongan Hills, Western Australia, took the first Mallee Hens he ever found on the 28th September (1842). Mr. T. Carter, further north, on the Murchison, has seen eggs in the hands of the natives 20th September. The season (1884) I visited the Mallee, in Victoria, laying commenced also in September. The season of 1888 another collector watched eighteen Mallee Hen mounds, and none contained an egg before the middle of October. Then again, taking thee terminal end of the laying season, and still in the same district (Wimmera), Mr. A. Esdaile, about the 27th March, found young birds just emerging from the shell; and later still, Mr. E. H. Hill, writing from Bendigo, under date 19th May, 1895, says: 'A pair of Mallee Hen's eggs were brought to the School of Mines from Boort, said to have been taken from the mound last Sunday. I blew them myself, and one was perfectly fresh, though the other was addled.'

Touching the complement of eggs to a mound, Gilbert stated that Mr. Roe, the Surveyor-General, who examined several mounds during his expedition to the interior, 1836, found the eggs nearly ready to hatch in November, and invariably seven or eight in number, while another authority informed him of an instance of fourteen being taken from one mound. Sir George Grey, also mentioned by Gould, says eight to ten eggs are laid, and if the mound is robbed, the female will lay again in the same nest, but will only lay the full number of eggs twice in a season. My brother, already mentioned, found thirteen eggs, some just hatched, in one instance. On one occasion, in the Mallee (Victoria), Mr. Charles McLennan states he found the extraordinary number of twenty eggs in a mound at one time, but, he adds, five of them were stale. Mr. James Macdougall, writing from Yorke Peninsula, South Australia, states: - 'The Mallee Hen breeds on the northern part of the Peninsula, where the mallee is tall, dense, and almost impenetrable to man. I was fortunate to meet a farmer, November, 1885, with a dozen eggs, which he had just obtained from a mound.' By far the finest lot I ever saw from the one mound was eighteen in the collection of Mr. W. White, Reedbeds, South Australia. They were all in the 'pink of perfection,' and apparently taken as they were deposited. The measurements varied from 3.68 to 3.36 x 2.38 to 2.27 inches.

Mr. Dudley Le Souëf informs me that the Mallee Hen will thrive in confinement, but does not as a rule attempt to make a mound.

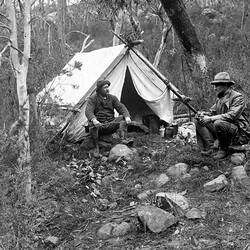

There is nothing like personal experience, and as the Mallee Hen is so replete with fascinating interest, even at the risk of being tedious, I here give a brief account, the substance of which I read before the Field Naturalists' Club of Victoria, 8th December, 1884, of a day's outing enjoyed in virgin mallee scrub of the Wimmera district of Victoria, when I was in quest of the Hen's eggs.

*I received a communication from Mr. K. H. Bennett, in which he writes:- "The paid of the nidification of the Mallee Hen appears to differ somewhat in Victoria, for I have never known them here (Mossgiel, N.S.W.) to commence con-structing their nests earlier than the middle of September (more frequently in October), whilst I have taken fresh eggs on several occasions from nests as late as the middle of March. I think the difference in time may be accounted for by the fact that the winters here are as a rule dry, the rain coming usually during the months of September and October, but it mainly depends on the season. During years of drought the birds do not nest at all, instinct apparently teaching them that without rain the attempt would be a failure.'

**Since writing my observations on the Mallee Hen, Dr. C. S. Ryan has kindly showed me a photograph which he took of a mound partly opened, exposing the top portions of eight eggs. They form an irregular circle, and are apparently nearly all about the same plane. - (A.J.C.)

***Since writing this statement, Mr. M. McLennan, at my suggestion, made the satisfactory observations that a fresh egg, marked on the 2nd October (1898), was hatched on or about the 12th November, or 41 days afterwards; another egg, marked on 4th November, he found hatched on the 12th December, or 38 days afterwards.

Resources

Transcribed from Archibald James Campbell. Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds, including the Geographical Distribution of the Species and Popular Observations Thereon, Pawson & Brailsford, Sheffield, England, 1900, transcribed from pp. 698-708.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types