VICTORIA RIFLE BIRD, (Ptilorhis Victoriae, Gould - 364)

Geographical Distribution - North Queensland, including Barnard Islands.

Nest - Oval in shape, open, shallow; somewhat loosely constructed of tough branching rootlets and a few broad dead leaves and tendrils of climbing plants; lined inside with a layer of broad leaves, upon which are placed portions of very fine twigs. Usually situated in dense scrub. Dimensions over all, 8 inches longest breadth, shortest breadth 6 or 7 inches by 3½ inches in depth; egg cavity 4 inches across by 1½ inches deep (See illustration.)

Eggs - Clutch, two; blunt or stout oval in shape; texture of shell somewhat fine; surface glossy, with a few crease-like lines running lengthwise; colour of a fleshy tint, streaked in various lengths and breadths longitudinally with rich reddish-brown and purplish-brown. The markings commence near the apex, which is bare or nearly so, extend about half-way down the shell and assume the appearance of having been painted on (boldly at the top and tapering downwards) with a camel-hair brush. Some of the markings are confluent, and appear as having been painted over each other. In one example, the longest single marking measured 0.48 inch by a breadth of 0.09 inch. Dimensions in inches of a proper clutch: (1) 1.24 x .92, (2) 1.24 x .89.

The type specimen of these beautiful eggs described by me in the Victorian Naturalist: 1892, figured by Mr. D. Le Souëf in the Proc. Roy. Soc. Vict. the same year, and now in the Australian Museum, has, in addition to the above-mentioned markings, a few small spots near the lower quarter and one large blotch of rich reddish-brown which has a smudged appearance. Dimensions in inches: 1.23 x .09.

Observations - This, the smallest, but none the less gorgeous of the Rifle Birds or Plumeless Birds of Paradise, is a dweller of the rich tropical scrubs of Northern Queensland, and its habitat is intermediate between the Rifle Bird of New South Wales and Queensland, and the Albert Rifle Bird of Cape York, being a limited strip of country of about 250 miles, extending from the Herbert River scrubs in the south into York Peninsula about the Bloomfield River district in the north.

Macgillivray, when surveying the North-east coast of Australia, discovered the Victoria Rifle Bird on the Barnard Islands and on the adjacent shores of the mainland at Rockingham Bay. On the islands he found three young males fighting, which he bagged with a single charge of dust shot.

Mr. Kendall Broadbent, who is undoubtedly a good 'field' authority on our northern scrubs, gives some very interesting details of the Victoria Rifle Bird. He found the bird in the mountainous districts inland from Cardwell even more numerous on the western fall of the range than anywhere else. In its peculiar district it is so common that Mr. Broadbent has seen as many as eight male birds while merely riding along the road through the scrub. The birds attain their full size the second year, but the plumage of the male is not perfect until the third year.

During the months of July, August and September (which Mr. Broadbent considered were the breeding season) the male bird is continually on the move, flying or hopping, and calling almost incessantly. On this latter account he is most easily obtained at this time of the year. After September, Mr. Broadbent relates, the male is very quiet, a fact that I thing would suggest its breeding season had only commenced, which, by subsequent discovery by other collectors of several nests with eggs, proved to be the case. The play-grounds and habits of the Victoria Rifle Bird are indeed remarkable, and aid is proving the affinity of Rifle Birds with Bower Birds. Mr. Broadbent proceeds to state: - 'Each male bird, as though by mutual agreement, has possession of a fixed domain, possibly some hundreds of yards in extent. In this area he has absolute rule - that is, as far as he can rule - and, if another male should enter on the ground, a fight ensues, the victor remaining in possession.

'A further interesting fact in this connection is the 'play-ground' used by each male bird. In early morning the bird resorts to his play-ground and there sports himself, now spreading his wings and rubbing them against the surface of the play-ground, and then whirling round with wings expanded. This he sometimes keeps up for a long a half-an-hour. No trouble is taken in preparing the ground, as in the case of the Bower Birds with their wonderful bowers. The bird simply selects the broken limb of a dead bum on the border of the scrub, a broken palm, or perhaps a dead stump; but, having chosen this, here he returns at dawn day after day, especially in (? before) the breeding season. Once having seen a bird at play in such a place, it is no difficult matter to obtain it is future; in this way I once procured a specimen which had selected a tree stump for its 'ground', and at a later date secured a second bird which had seemingly inherited the vacant property.'

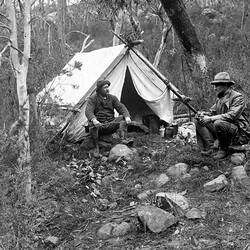

One of the chief objects of my trip to Queensland in 1885 was to gain, if possible, some information respecting the nidification of this Rifle Bird, which was up to that time a sealed book, or one of Nature's secrets. Although I did not succeed in procuring eggs, I had better give the story of our glorious outing amongst the birds themselves as it appeared in the columns of The Australasian, under the title to 'A Naturalists' Camp in Northern Queensland,: my companions being Messrs. A. and F. Coles, Melbourne, and Mr. A. Gulliver, Townsville: -

'While encamped at Cardwell, we determined to see the Rifle Bird in its native element, and, if possible, procure skins, and, as the Rockingham By variety was rarest, we were doubly anxious for success. Having failed to observe any of these birds on the mainland, and knowing that they were tolerably plentiful on some isolated islands up the coast, we resolved to enlist our friend, Mr. Walsh, sub-collector of Customs, into our services. We had no sooner made known our errand than he replied a trip could be capitally arranged, because he had officially to visit that part of the coast, and could go with us in the pilot cutter. It was a delightful morning as we left the camp behind and briskly 'pegged out' for town, where we arrived at half-past eight o'clock. The tide was unfavourable, and we did not get aboard till two hours later. Leaving port we had a fair wind, but when we got outside the bold land of Hinchinbrook Island the weather was rather dirty, with a strong south-each wind. We soon reached the Family Islands, a group of five, with slopes more or less grassed to the water's edge, where the blue sparkling water, grey rock, and green sward formed agreeable contrasts. Dunk Island was passed on the weather side, then King's Reef, which runs between Clump Point on the mainland and the two South Barnard Islands.

After a fair run of thirty-five miles we made the North Barnard, a group of five islets lying at various distances up to two-and-a-half miles from the mainland, and dropped anchor at about half-past four o'clock to the leeward of the largest and outermost island. Here our little craft strained at her anchor, pitching and tossing all night, much to the discomfort of invalided passengers. At sunrise nest morning our skipper pronounced the surf too great to enable the dinghy to land us with safety. This news was a great disappointment to us, especially as we were only a few cables' length from our much-coveted goal, so we decided to run for Mourilyan Harbour, on the mainland, distant about five miles, to wait until the weather moderated.

'Next morning at daybreak it looked calm outside, with a gentle land breeze we quietly slipped out, and before breakfast were once again riding at anchor off the outer Barnard. The island rises out of the Coral Sea to an elevation of about three hundred feet. It is half-a-mile long by a quarter broad, and enshrouded in luxuriant vegetation. Trees great and small show above the prevailing dense scrub. Although we appeared to be close in shore, it was a long row in the dinghy. A curling wave shot us on to the coral strand, which was bordered at hight-water mark with large, strongly-perfumed lilies (Crinum asiaticum), growing from broad flat-like leaves. A beautiful convolvulus (pomoa) of blue and purple festooned the nearer bushes. Up the face of the island large, noble and beautiful trees, the botanical name of which we had not learnt, met our gaze, contrasted with figs (Ficus magnifolia), Pongamia glabra, bearing large seed pods, and Ixora timorensis in flower, interlaced with small species of lawyer palm, and overgrown with innumerable creepers, pothos, and other climbers. I clambered up the face of a rough, rocky surface, with loose dark mould, sustaining crops of bird-nest ferns among vines and supplejacks; progress was rendered not only slow but difficult. When about half-way towards the summit of the island, I moved across the face and dipped into one of the numerous gullies or hollows which ran down to the sea. Here, with a fair outlook up and down hill, I waited the turn of events. Presently in the thicket I heard 'scrape'. My breechloader brought down through an entanglement of vegetation my first Rifle Bird - a female. After remaining in ambush some time I secured another female and returned to the strand, where I met the other members of the party in great ecstasies over a lovely male bird.

'Luncheon over, we took to the scrub, which was now uncomfortably damp from passing showers. After scrambling about until the perspiration was literally rolling off me, and as it had commenced to rain in earnest - real tropical showers - I thought, instead of chasing the birds, I would try an experiment and let them chase me. The idea was good, because after I had waited for some time there flew past me a lustrous black bird with rounded wings and of compact appearance. During flight its feathers produced a peculiar rustling noise like a new silk dress. Between thirty and forty yards off it alighted, and darted behind some green branches. In an instant, reckoning on the intervening obstruction, I discharged No.6 instead of dust shot. I was immediately surrounded by thick smoke hanging in the damp air, but whether my beautiful feathered visitor had fallen or flown I knew not. Overcome with excitement, I felt as if I could hardly venture to ascertain. I crawled slowly up the gully through prickly creepers, and on parting a bush there I beheld a gorgeous male Rifle Bird, dead, upon its back. It was a beautiful object in its rich shining garb.

'Two males and one hen fell to the second member of the party. The botanist was a long time in showing up, so we conjectured that he was either lost or had obtained a big bag. Both surmises proved correct. Every attempt he made to reach the beach he found himself on the wrong side of the island, but during his wanderings he 'bagged' no less than three males and seven hens. When he emerged from the scrub he looked a woebegone sight, dripping wet, scratched and bleeding, hair over his forehead, with gun in one hand, while under the other arm were the birds carefully rolled up in his hat. We enjoyed a hearty laugh. We soon got afloat, changed our clothes, and refreshed ourselves with a warm supper. Then followed the reckoning of the day's work - grand total, seventeen Birds of Paradise - the greatest day's taking of rarities recorded in the annals of Australian ornithology. Certainly it was a most unfortunate day for the poor birds, and for their sake let us hope it may never occur again. We were the best part of the night turning our booty into skins. The weight of one of the birds was a little over two ounces. About midnight we left our anchorage, and turned the cutter's nose towards Cardwell, wishing to reach port before Sunday. Good headway was made at the beginning but at sunrise the wind died almost away, and we drifted on leisurely, aided by wind puffs and tides. It was a most charming day - above a cloudless vault, below the ocean, true to its name, Pacific. Lovely islands were slowly passed, behind which could be seen the mainland melting into distance. Taking all things into consideration, especially the unqualified success of the object of our cruise, we felt supremely happy.

'The success we met with during the eight hours we spent among the Rifle Birds only whetted our appetites for more information, especially as the dissection of one female bird proved that the breeding season had commence, and the finding of a nest would be the greatest oological discovery of the day. Therefore we agreed to undertake another trip.

'The Burdekin steamer (Captain J. Keir), a regular northern trader, was due at Cardwell from the south, and gave us the chance of staying two days at the islands. Terms were soon agreed upon, and once more our party left Cardwell. We were provided with a tent and a breaker of fresh water, the island being without springs.

'The steamer arrived abreast of our island shortly after three o'clock. The captain put us into the steamer's boat, and in landing we had much difficulty in keeping our paraphernalia dry on account of the surf. Our tent was pitched between two palm-like pandanus trees, surrounded by strongly-perfumed lilies and thick foliage, adorned with convolvulus. The richly-wooded slopes of the island completely sheltered us on the windward side. Being in the Coral Sea, and under the protecting influence of the Great Barrier Reef, whose nearest edges were not more than ten miles off, we felt perfectly secure in our insular quarters. Winds might blow and storms beat, but no great billows can ever disturb these tranquil shores. The islet we were on had not been specifically names before, so during a passing shower, in the name of all that is beautiful in nature we christened it 'Ptilorhis,' that being the name of the lovely Rifle Bird so abundant in its scrubs. Notwithstanding the evening being showery, we climbed to the summit of Ptilorhis Island but the result was nil. In our tent we spent a tolerably refreshing night, somewhat broken, however, by the annoyance caused by numerous indigenous bush rats, which are not quite so large as common city vermin. They are known as the long-haired rat (Mus longipilus) of Gould. These rats had not seen human being before, for they made themselves so uncommonly familiar as to run over our bodies. A pistol was discharged among them. The echo of the report from the island opposite had barely died away before the impertinent intruders were at their little games again.

'Wednesday, September 9th, was a bright day in our calendar. By daylight and before breakfast we entered the wet scrub, and were rewarded with a brace of beautiful White Nutmeg or Torres Strait Pigeons. These pigeons were just beginning to arrive from northern latitudes. They roost at the islands at night, returning to the mainland to feed at sunrise. We saw dozens of last season's nests. Although we heard their loud 'coo' in different places, the pigeons were difficult to sight through the thick foliage of the trees in which they sought refuge. After being much embarrassed by the wet-scrub and canes, I got a splendid male Rifle Bird and a brace of hens (their plumage being at perfection at this period of the year). I then dropped into a sylvan nook to watch the actions of the birds around me. Here tall and thick foliage almost shut out the light of day. Pretty little Rufous Fantails darted at me as if I intruded upon their particular dominions; Zosterops chirped overhead; Megapodes or Scrub Hens chased each other through the underwood, and, not detecting my presence, passed within a few feet, uttering curious crying calls. Where the ground was loamy they were patching up their huge egg-mounds for the coming season - interesting in their way, but the subject preoccupying my mind was Rifle Birds. At one time I was surrounded by no less than two male Rifle Birds and five hens; some were on the ground turning over small stones and leaves in search of food, others were preening their beautiful quills or stretching their necks from behind a limb to watch me. Both male and female occasionally uttered the peculiar hoarse, guttural 'scrape' noise, which was sometimes repeated twice in succession. I could not sufficiently admire the splendid shining appearance of the male bird in every position, but when it darted through the rich green foliage or posed upon a rock it was really a superb creature. I felt convinced that the majority of the birds had not commenced to breed, so at intervals I fired small charges of dust-shot, and secured a pair of fine males and one hen. We all turned up at the tent hungry and wet, and over a warm 'billy' of tea exchanged experiences. The takings were distributed as follows: - The botanists, a pair of Rifle Birds and a pair of Pigeons; the younger brother, a pair of Rifles, a Megapode, and such small fry; and myself, three pairs of Rifles. Although a sharp look-out was kept none of us saw any traces of nests.

'Rats were again troublesome at night. They ran off with our preserved milk tin, and also destroyed one of our fine Pigeons. In the morning we expected the steamer, therefore we chiefly occupied ourselves in striking camp, &c., and gathering collections of sea-shells. These were volutes, cowries, cones, in end-less profusion, the majority being empty. The beach was entirely composed of fragments of dead coral, hard as cement, washed up by the sea. When the tide was out the rocks, which are of singular form-ation, like those of the island, bespangled with mica crystals, retained innumerable curious marine creatures, such as small fish, water snakes, a most remarkable roundish animal furnished with long brittle spines, live coral of bluish tint, &c. Abundance of oysters adhered to the rocks. After a while the 'Burdekin' hove in sight. Since our landing the surf had increased considerable, and the crew had to manouvre to keep the boat from being swamped by the breakers while taking us off. Without mishap, Cardwell was reached at six p.m. Thus ended our second excursion to the Barnards (or Ban-ards, as many persons insist upon calling them, by placing the accent on the second syllable), making a most agreeable climax to our 'Naturalists' Camp in Northern Queensland.'

In 1887 I received from Mr. Charles French, F.L.S., the supposed nest and eggs of the Victoria Rifle Bird, which I described in the 'Naturalist' of that year. The specimens were found in the Cardwell Scrubs by an intelligent reliable collection of Mr. French; but upon Messrs. Le Souëf and Barnard's subsequent discovery, it appeared the collector, Mr. French, and myself had been misled - the old story of "one fool makes many.'

The honour of the first authenticated discovery of the nest and eggs of the Victoria Rifle Bird rests with my friends, Mr. Dudley Le Souëf and Mr. Harry Barnard, who visited the Barnard Islands and as if drawn by psychological influence, actually pitched their camp under a tree which was afterwards found to con-tain a nest and egg, and the hen of the rare bird sitting thereon.

The following is Mr. Le Souëf's own description of the finding of the nest: - 'The nest was found 19th November, 1891. Mr. Harry Barnard and myself watched the hen bird for some time, and saw her fly into the crown of a pandanus tree growing close to the open beach. Although we could not distinguish the nest itself, we could see the head of the bird as she sat on it. The nest was about ten feet from the ground, and the bird sat quietly notwithstanding we were camped about five feet away from the tree.'

Meeting Mr. Le Souëf at Brisbane on his return home, I was one of the first to see his new and interesting discovery. He, with characteristic thoughtfulness, permitted me to describe the nest and egg. I took the earliest opportunity of doing so by describing them at the next (December) meeting of the Field Naturalists' Club, and thereby corrected my former error. The egg was afterwards figured by Mr. Le Souëf in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria, and finally found a secure resting-place, as the type specimen, in the collection of the Australian Museum, Sydney.

It would appear that Messrs. Le Souëf and Barnard visited the inner Barnard Islands, and not the outer, where my party and I found the Rifle Birds so numerous.

Mr. Le Souëf made further inroads into the secluded domains of the Rifle Bird, but this time on the main-land in the Bloomfield River district, where he found the birds fairly plentiful in the scrubs, especially near the coast, their harsh note being often heard. They were by no means shy, and seemed to be very local, but great difficulty is attached to finding their nests. One was discovered 29th October in a fan palm, not far from the ground, by the blacks when clearing a place for their camp. It contained a pair of beautifully marked eggs. Before Mr. Le Souëf left, he found another nest building in a cordyline, only about seven or eight feet from the ground. The nest was carefully watched, and the eggs were taken on 20th November by Mr. R. Hislop for the finder. These eggs, a perfect pair, the third recorded find, and with a history so complete, now adorn my collection.

Mr. Le Souëf saw a pair of Rifle Birds endeavouring to drive a Black (Quoy) Butcher Bird from the neighbourhood of their (the Rifles') nest, when they uttered a different note to their usual one. In building, according to Mr. Le Souëf, the Rifles seem to possess an extraordinary fascination for shed snake skins, as in two instances he saw pieces of snake skin worked into their nest, one piece being about three feet long, most of which was hanging loose. The hen bird, when sitting on her nest, is not easily disturbed.

Mr. W. B. Barnard, who, with an English friend (Mr. Albert Meek), was collecting in the vicinity of the Bloomfield River at the time of Mr. Le Souëf's visit, has kindly supplied his field notes respecting the nidification of the Victoria Rifle Bird. He says: - 'Three nests with two eggs each were found. Two eggs were broken. The nest is often built in the fan palm, right at the trunk of the tree where the fronds join, fairly well hidden amongst the fibre. Mr. Le Souëf gives a good photograph of the nest. In one nest a snake's skin hung from inside down two feet. These birds build from the first week in September till the end of November.'

Resources

Transcribed from Archibald James Campbell. Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds, including the Geographical Distribution of the Species and Popular Observations Thereon, Pawson & Brailsford, Sheffield, England, 1900, pp. 69-75.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types