Summary

Museums Victoria holds a small but siginificant collection relating to the experiences of Hungarian migrants to Victoria. These people are part of a long and complex history of Hungary and their objects provide personal perspectives on a collective narrative.

Museums Victoria's collections of more than 16 million artefacts includes items that were once personal treasures and are now part of the national memory, including its migration collections. What did migrants bring with them to Australia? What tangible and intangible things and how has their culture shaped life in Victoria? The Museum is home to a small number of objects that may provide some insights into the experiences of Hungarians who migrated to Australia after World War II. There are several reasons for leaving one's own homeland, and also in the case of Hungary, the sometimes damaging consequences of historical events had a significant impact on this crucial decision.

Hungary lies in the middle of the European continent, in a rather flat, very water-rich area, bordered by the mountain range of the Carpathians. Today's capital, Budapest, used to be an outpost of the Roman Empire, the Pannonian province called Aquincum. Shortly before the first millennium A.D. the ancestors of today's Hungarians came to the Carpathian basin and conquered the area. The Magyars, once nomadic equestrians with shamanic beliefs, eventually united their tribes under the auspices of Christianity and became one nation.

Hungarians arrived in Australia as early as 1848/49 as a result of their freedom fight against the Habsburgs. The few hundred Hungarians who arrived in Australia during the 19th century settled mostly in Melbourne.

By the First World War, the Hungarian migrants already living here, as well as Turks and Bulgarians, who were also Germany's allies, had to submit to special restrictions in their daily lives. This was ironic in the case of the Hungarians, since most of those who left their homeland wanted to turn their back on the Habsburg rule. As citizens of the Austro-Hungarian Empire they had become enemies of the British Empire.

After the end of the First World War, following the Treaty of Trianon in 1919/20, Hungary was deprived of two-thirds of its territory, and three million Hungarians suddenly found themselves the marginalised minority in another nation. Many of them and their descendants came to Australia. In particular, the number of the people who migrated to Victoria from the formerly southern Hungarian territories was relatively large.

During Hitler's seizure of power, some European Jews also fled to Australia, among them Hungarian Jews in the 1930s. The post-war displacement and resettlement people from east and southeast Europe, including Hungarians, affected about 14 million people. Some of these displaced persons, as well as others who did not agree with the subsequent Soviet regime, came to Australia at that time.

Another significant event for the people of Hungary, and another motivation to leave their beloved country, was the lost revolution against the Soviet occupation under which the population had suffered since the end of the war.

On 23 October, 1956 thousands protested in the streets of Hungary against poverty and Russian control. On 4 November, Russian troops invaded Budapest with 1000 tanks in the early hours of the morning and fought a battle with the Hungarian army and the citizens. In the lost fight for freedom and independence, it is estimated that about 4000 people died, 22,000 were imprisoned, and another 200,000 fled westward. About 25,000 of them eventually came to Australia. In several waves, Hungarian settlers arrived in Australia during the second half of the 20th century. Most settled in Melbourne and Sydney. Today, Melbourne has the largest Hungarian community outside Hungary. About 60,000 people speak Hungarian in Australian homes, and nearly twice the number is Hungarian-born.

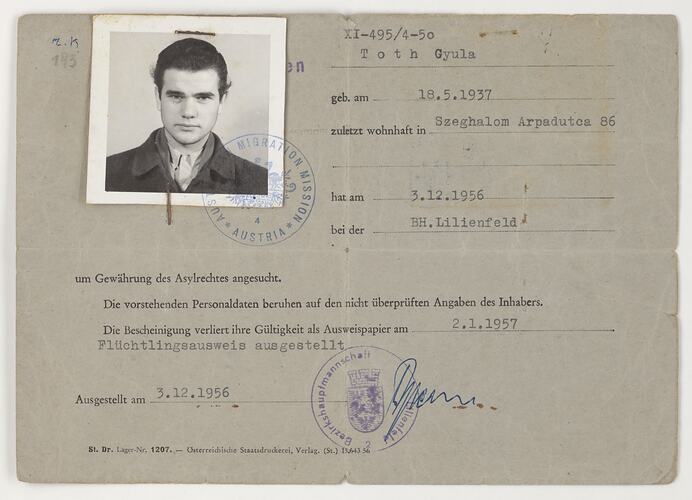

The Museum's collection relating to Hungarian immigration, is relatively modest. It was mostly created in the 1990s in cooperation with a few members of Melbourne's Hungarian community. Of particular note is the collection of Gyula Toth (later he changed his name to Julius Toth). He arrived in Melbourne at the age of 19 on 22 March, 1957. His story is one of many. And yet a closer look helps to discover the individual story within the collective experience.

To enable objects to speak, they need to be given their historical context. For instance, a simple train ticket marks a turn in Julius' life, which substantially altered his destiny; a demarcation line in the life of a person that so many people have crossed. It is not just fate, a personal memory, but a cultural memory that has shaped an entire generation and has been incorporated into the canon of one culture, a trauma that can still be felt today. This ticket represents the act of escaping, a testimony of an event that has been kept and valued as a memento of this life-changing act.

The people who have donated their objects and stories to the Museum provide examples of Hungarian migration narratives. It is the Museum's responsibility to ensure that no single or stereotyped image of an immigrant group arises. Nonetheless, one of the thrills of discovering the stories of these people is to provide a personal insight into one aspect of Australian history.

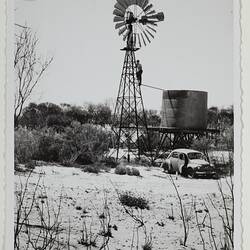

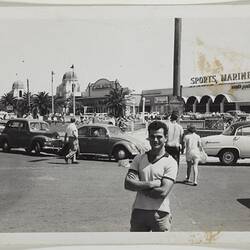

Gyula Toth's story is well documented through the personal collection he donated to Museums Victoria. There are photographs, his mouldering tools, documents and an almost empty pack of Kossuth cigarettes. All these items represent key events, people and milestones in his life.

To illuminate the history through a collection can contribute to understanding today's socio-political developments. Having a story talk through objects has its limitations. Nevertheless, it can help to offer new perspectives and place historical events and collective trauma into another context.

Why did Gyula leave one Kossuth cigarette in his packet? Perhaps because Lajos Kossuth, the freedom fighter of 1848/49, fought against foreign rule and therefore was a national hero for the revolutionaries of 1956, who fought against another foreign rule? Cigarettes were a coveted commodity on the six-week crossing from Amsterdam to Melbourne. Nevertheless, he still kept a Kossuth.

Réka Mascher-Frigyesi M.A. This article was written for Museums Victoria as part of a mentoring-program, funded by the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt, 2018. Réka Mascher-Frigyesi is doing her PhD in Social Anthropology and is a member of the Research Training Group 'Value and Equivalent'.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types