Love-letter, ubhala abuyise, meaning 'one writes in order that the other should reply'. (Levinsohn, 1984)

Beads have long been used as trade items by European and Arab merchants in southern Africa, along with indigenously produced brass, clay and ostrich shell beads, cowrie shells from the Indian Ocean, seeds, aromatic wood, animal claws and teeth as objects of personal adornment. Arab and Swahili merchants traded Indian, Persian and Middle East beads in exchange for ivory, gold and slaves. Venice bead-makers were major suppliers to the early Portuguese merchants. However, until the industrial revolution of the 19th century, glass beads were hand-made and relatively expensive. The glass beads which feature in the Museum's beadwork were not made in Southern Africa. They were manufactured in Britain, Germany and Czechoslovakia for European merchants trading in Africa.

Shaka, the famous Zulu king (died 1828), reorganized Zulu society, with military regiments based on age-grade regiments sent to raid neighbouring tribes and establish a tributary empire. It was a centralized kingdom and Shaka realized the potential of trade beads as luxury items, which could be used to reinforce the social order. He restricted their use to members of his court and those in royal favour. Objects of adornment were produced by women of the royal enclosure (isigodlo) and presented by Shaka as gifts to lesser chiefs and outstanding warriors. They became prestige items, restricted to the elites.

There are indications that colour preferences changed under different rulers. Dingane, Shaka's successor, was said to have preferred green beads (Gardiner, 1836), while Mpande, Dingane's successor, preferred blue, red and white beads. (Angas, 1849)

The British finally defeated the Zulu in 1879, at the end of the Anglo-Zulu War. The kingdom of the Zulu paramount chief, Cetshwayo (Mpande's successor), collapsed and civil war ensued among the Zulu. Cetshwayo died in British protection in 1884. His successor, Dinzulu, tried to reassert his authority but, in 1887, Zululand was formally annexed as a colonial territory by the British and Dinzulu was sent into exile. Zululand was administered as a separate territory under the authority of a British 'Resident' who ruled through government-appointed petty chiefs and was himself responsible to the British High Commissioner in Southern Africa, until Zululand was merged with Natal in 1897.

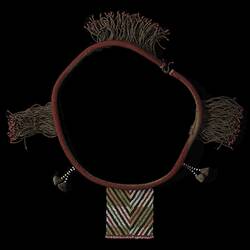

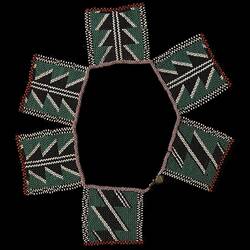

With the destruction of centralized Zulu authority, control over the distribution and use of beadwork broke down. Suddenly commoners could wear whatever they could afford. The girl's waistband [collection item number X 7260] is illustrative of the skill of Zulu bead-working of the late nineteenth century.

Dr David Craig Dorward (retired), formerly Director of the African Research Institute, LaTrobe University.

References:

R. Levinsohn, Art and Craft of Southern Africa: Treasures in Transition (Johannesburg: Delta Books, 1984) p. 84.

A.F. Gardiner, Narrative of a Journey to the Zoolu Country (London: William Croftts, 1836), p. 49.

G. F. Angas, The Kaffirs Illustrated (London: Hogarth, 1849; John William Colenso, D.D., Ten Weeks in Natal: A Journal of a First Tour of Visitation Among the Colonists and Zulu Kafirs of Natal (Cambridge: MacMillan & Co, 1855).

Emma Bedford , "Exploring Meanings and Identities: Beadwork from the Eastern Cape in the South African National Gallery", Ezakwantu: Beadwork from the Eastern Cape (South African National Gallery: 1994), pp. 15-16.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types