Beadwork had always been a female activity and it was in the late nineteenth century that beadwork began to take on symbolic meaning in Zulu courtship. As trade-beads were becoming increasing accessible in the rural areas and royal power waned. Unmarried girls would gather together in their homestead to make beadwork, initially learning techniques from the older sisters. It served as a bonding activity. As their skills and courtships developed, girls would help each other to make beadwork with innovative designs.

The most elaborate beadwork was worn by unmarried young women. The very fine Zulu waistband, the umgingqo with brass button fasteners [collection item X 7262], was collected in the later 19th century by Sir Henry Brougham Loch. But girls not only made beaded adornments for themselves, they also used beadwork as love-tokens, to express their interest in a suitable young man. There wasn't a written language but girls and women created beadwork with coded means based on coloured patterns that expressed their feelings for a potential boyfriend, lover, and husband. It often began with a gift of a single strand of white beads (ucu), threaded onto a length of sinew. By accepting and wearing the ucu, he reciprocated her advances.

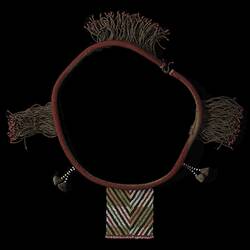

The next basic form of courtship beadwork was the amatikithi or 'thickets', a length of white beads with loose tassels of various colours, which could be 'read' to interpret her messages of purity, desire, despair anxiety, all the emotions of courtship.

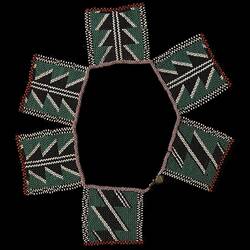

As their relationship developed, the beadwork became increasing elaborate, with what are commonly referred to by Europeans as 'love letters' (but called by the Zulu isigcina). As beads became more readily available, large bibs or 'tongues' (ulimi) were added [collection items X 7346, X 33724, X 43241], worn by men on their chest.

While beads or combinations of beads can refer to stock courtship phrases, it would be wrong to assume that 'love letters' or isigcina sentliziyo ('keeper of the heart' pendants) have a language that can be universally 'read'. The 'language' of beads is much more complex. The means attributed to particular beads have changed over time and can vary significantly even between neighbouring communities. Subtle differences in the shade or intensity of colour of beads can influence their meaning. There is no fixed code for the means attributed to colours or designs, and such elements vary widely across regions and with the fashions of the times. Even within a very close parochial community, the message can be so cryptic that a young man has to ask his sister to translate for him.

Different colours embodied different means, negative as well as a positive connotation: red beads can stand for passion and desire but also anger and pain, green beads can stand for grass and thus fertility but also sickness and discord; yellow can symbolize pumpkins and thus wealth and fertility but it can also represent thirst and withering away. The only colour that is consistently positive in white, symbolizing purity.

In Qebe area yellow and green beads were used to celebrate fertility, but in Zululand yellow can imply wealth and green sickness. Furthermore the dominance and order of the colours can completely alter the local interpretation. Through the introduction of subtle variations in the limbs, female figures in 'love letters' or isigcina sentliziyo ('keeper of the heart' pendants) can imply such divergent messages about wives as 'a very lazy gossip who has two children' or 'one who loves to dance but whose feet are worn out by age.' (Bedford, 1994) The 'meaning' of the beadwork was not 'alphabetical' but represented ideograms, often very parochial in their meaning and changing over time.

As their relationship grew, girls would produce an increasing array of objects of adornment for their boyfriends, including armbands, waistbands, anklets, bandoliers worn across the chest, and loin ornaments, for example, the coil of material covered in a sheath of beadwork often with geometric designs, known as umgongqolozi. These 'love letters' (such as collection item X 87032), were worn by both males and females.

In Zulu society, being a polygamous culture, young men could be seen wearing a number of different girls' isigcina sentliziyo or 'love letters.'. Moreover, 'love letters' were not an engagement pledge. The actual sign of intention to marry was a long ucu or single strand of white beads, two or three meters long, coiled around the neck. On the second day the ucu was doubled and twisted to form a rope. Both the boy and the girl wear such an ucu rope as a sign of betrothal. However, if a girl is jilted, her friends may make a ucu rope of black or black and white beads and throw it at the feet of the offending young man, who was expected to wear it at least once or be branded a coward.

Christian missionaries looked upon Zulu beadwork as a 'pagan' influence. Initially, many missionaries tried to prohibit the practice amongst converts but increasingly mission schools taught girls to do beadwork that resembled the more lacelike Victorian and Edwardian British beadwork. Such 'lacework' was also often incorporated into more traditional pieces.

As literacy became more common, the use of beadwork as a vehicle for communication died out. While beadwork remains popular in Southern Africa, often as an expression of ethnic solidarity, and sold in vast quantities to tourists, few today know the 'language' of beads.

The oldest beadwork in the Museum's collection was collected over a hundred years ago by Sir Henry Brougham Loch, GCMG, GCB, Governor of Victoria from 1884 until 1889. He was appointed as High Commissioner for Southern Africa and Governor of Cape Colony, serving from 1889 to 1895. He died in England in 1900 and the collection was acquired by Museums Victoria in 1904. We can't know what the colours and designs meant to the women who made them so long ago. Other examples of Zulu beadwork in the Museum's collection date from the 1920s to 1930s.

Zulu beadwork 'vocabulary'

-White beads (obumhlophe); purity, love, honesty

-Black beads (obumnyama) The oxhide skirt - isidwaba, which is coloured black and worn by married women: 'I am ready to marry' but also morning, sadness

-Red beads (obubomvu) passion, tears, desire but also anger and pain

-Pink beads (Obumpofu) Poverty (she loves him even though he is poor)

-Yellow beads (Obuncombo/Obuphuzl) wealth, fertility

-Green beads (Obuluhlaza) new life, fertility but also sickness and jealousy

-Royal blue (Obujoli) Loyalty

-Tuniquose blue (Obulwandle) love like the sea, clean and pure

Dr David Craig Dorward (retired), formerly Director of the African Research Institute, LaTrobe University.

References:

R. Levinsohn, Art and Craft of Southern Africa: Treasures in Transition (Johannesburg: Delta Books, 1984) p. 84.

A.F. Gardiner, Narrative of a Journey to the Zoolu Country (London: William Croftts, 1836), p. 49.

G. F. Angas, The Kaffirs Illustrated (London: Hogarth, 1849; John William Colenso, D.D., Ten Weeks in Natal: A Journal of a First Tour of Visitation Among the Colonists and Zulu Kafirs of Natal (Cambridge: MacMillan & Co, 1855).

Emma Bedford , "Exploring Meanings and Identities: Beadwork from the Eastern Cape in the South African National Gallery", Ezakwantu: Beadwork from the Eastern Cape (South African National Gallery: 1994), pp. 15-16.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types