The Argus, 22nd November, 1887

THE FIELD NATURALISTS' TRIP TO KING'S ISLAND

INTERESTING RESEARCHES

THE ISLAND FORMERLY PART OF TASMANIA

(BY A SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT)

The wind was blowing freshly as the Lady Loch left Port Melbourne pier on the evening of Wednesday, November 2, giving promise of an uncomfortable night for the party of field naturalists whom, by kind permission of Mr. Cuthbert, Acting-Commissioner of Customs, she was carrying to King's Island.

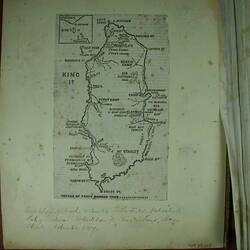

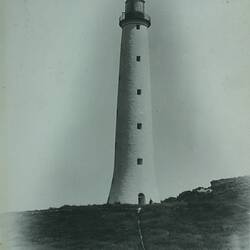

It was with feelings of great relief that early next morning we sighted Wickham lighthouse, and descried in the distance the outlines of the low-lying sand hills bounding the island which was to be our home for the next fortnight. Up to the present time King's Island has been known only to a very few hunters and the in-habitants of the two lighthouses erected by the Tasmanian Government to warn passing ships of their nearness to its dangerous reefs. It was our intention, before the introduction of numerous foreign plants and animals rendered it impossible to do so, to ascertain as precisely as we could in the short time at our disposal the fauna and flora indigenous to the island. It is felt to be most important from a scientific point of view that this should be done in the case of as many islands as possible which have no yet been stocked from foreign countries. The question of the present distribution of animals and plants, and of why certain forms should be found in particular parts of the world and nowhere else, intimately connected as it is with the past history of the earth's surface, is one which has for long attracted the attention of scientific people. Though so near to one another Australia and Tasmania present distinct differences in both their native animals and plants; and halfway, roughly speaking, between the two lies King's Island, associated politically with Tasmania. It was our intention to see if this union with the latter held true as well naturally as politically. Our party numbered 26 in all, and was composed of members of the Victorian Field Naturalists' Club, by whom the expedition was planned. Some of us were sportsmen, some oologists (i.e., scientific birdnesters), some botanists, some con-chologists, some experienced taxidermists, but for the time all were transformed into collectors of anything which might throw light upon the living inhabitants, both animal and plant, of the island. We were landed on the western coast some 12 miles to the south of the Wickham lighthouse, and after an hour or two spent in carrying stores on land saw the Lady Loch steam away towards Melbourne. To be once more on land was a great relief after our experience of the night just passed, but we were as yet houseless, and our first work was, naturally, to choose a good camp site. An excellent one, than which it would have been difficult to choose a better, was found on the banks of the Yellow Rock rivulet. Owing to the heavy surf we had been landed about a mile and a half to the south of this. It was no light task to carry up to camp our tents and the stores wanted more immediately. However, tents were pitched, camp fires lit, and such heavy packs as could not be carried without the aid of horses put in places of protection against the threatened rain before many hours were passed. We settled down to a comfortable evening, content to read a little before our real work began.

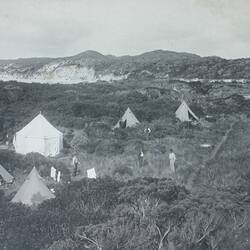

Our camp lay in a sheltered nook, beside Yellow River Creek, the waters of which, though quite fresh and drinkable, were coloured brown as those of most other streams on the island by reasons of its flowing through boggy swamps inland. On all sides we were surrounded by sandhills, hemming in a horseshoe-shaped curve in the river; and, seen from the top of the hills behind, the camp with its 10 tents presented, especially towards evening when camp fires were lit, a very picturesque appearance. The next morning was spent in bringing up to camp the remainder of our stores, and then, fortunately not till this was finished, the rain began to fall. In spite of this most of us wandered out, not going far from camp. Along the shore, going southward, the beach is broad and sandy, with jutting rocks of granite running out to sea. Near at hand are still the remains of the Ocean Bride, one of the many vessels wrecked on the west coast of the island. The sand hills are covered largely with smoke-bush, currant-bush, and a form f grass sending out long creeping stems, which serve admirably to bind the loose sand together. This binding grass (spinifex hirsutus) is very abundant all along the coasts of the island. Out to the west lay New Year's Islands, forming the only shelter along this side from the west winds, and some four miles south of the Yellow Rock is a jutting promontory known as Whistler's Point. Amongst these rocks at low tide many interesting sea forms were found - the ear shell (haliotis), various species of the limpet (patella), the curious shell chiton, one of the most interesting and primitive of molluscs, and peculiar in the possession of eight shells arranged along its back, a considerable number of sponges, polyzoans, starfishes, and sea anemones, whose colours made beautiful the rocky pools, and a great variety of seaweeds, specimens of all of which were brought home. Along the shore great quantities of kept were thrown up; in fact, the abundance of this is a striking feature in the island, and its smell when decaying is far from pleasant. At times we sank almost knee-deep in a brown slime formed by its decomposition, and under such circumstances walking was neither easy nor pleasant. Inland at this part are a series of lagoons running parallel with the cost, containing perfectly fresh water, in which char grows in abundance. It seems to contain an unusual amount of mineral deposit in its leaves, and forms great masses spreading over the whole space occupied by the lagoon. Along the shore the sooty and pied oyster catchers are frequently seen, and the hooded dotterel in abundance.

Inland from the camp we wandered over a flat plain extending for some few miles, part of which had evidently been once cultivated. Lucerne grows luxuriantly, and the soil, black in colour, appears capable of producing rich crops. The Yellow Rock Creek meanders about and in parts the granite comes to the surface, whilst further inland are patches of burnt blue gum trees (eucalyptus globulus), and in many parts scrubs, with ti-tree now in blossom. Small lagoons are found surrounded by the latter, and on their surface a few ducks and teal (anas castanea) are seen, but the whole plain reveals but little animal life. In the ti-tree scrub we captured alive a ring-tailed opossum, whilst everywhere the superb warbler (Malarus longicarda), a bird found in both Victoria and Tasmania, is abundant. The next day (Saturday) was again wet; the prospect began to look gloomy, and the day was spent near camp, our list of captures receiving, however, considerable additions. It became evident that so far as the district immediately around our camp was concerned there was not a great amount of game to be captured, though specimens of a considerable number of genera were added to our list.The first two days' work amongst birds revealed very clearly the fact that we were on ground peculiarly Tas-manian and not Victorian, and it may be stated at once that this is undoubtedly the case as regards the whole island, judging from the higher forms of animal life. So far as these are concerned - and doubtless the plants and lower forms of life, insects, mollusca, &c., will tend to strengthen this conclusion - the fauna is very distinctly Tasmanian as opposed to Victorian. Thus, for example, the birds taken this day were the scrub-tit (Sericorius humilis) of Tasmania, and perhaps Victoria; the Tasmanian fly-catcher (Rhipadura sp.?), the yellow throated honey-eater (Pulotis flavigula) of Tasmania, the strong-billed honey-eater (Melithraptus validirostris), the gan-gan cockatoo of Tasmania and Victoria, the yellow-billed paroquet of Tasmania (Platycereus flavi-ventris), and the Cygnis strata, the black swan of Tasmania and Victoria, and the Rufus-headed grass warbler, remarkable as being he solitary bird secured upon the island which is found in Victoria, and never met with in Tasmania. Sunday again broke wet and cloudy, and was spent quietly in camp and in wandering along the shore and inland. As the day wore away the clouds lifted, and we hoped for better things, and made plans for the coming week. One party was to go across country to the east coast, another to go south to Currie Harbour, and another north to Wickham lighthouse. Early on Monday, accompanied by the hunter Henry Grave, whose knowledge of the various tracks (the only means of passing through the dense scrub inland) was of invaluable service to us, the east coast party left the camp, and, with two pack-horses and some dogs for hunting, started northward along the beach. We were ten in all and quite prepared for hard work, and, as it turned out, had plenty of this to do. The shore is formed of sand hills for about six miles, with the exception of one part in which, for a small distance, an outcrop of limestone occurs. On the shore, under old logs, the remnants of wrecks, were found beetles, centipedes, and earth worms, together with the usual sand-hoppers (Talitrus locusta) in abundance, though not infrequently all must be bathed at high tide in water, and it was strange to find together this mixture of very-distinctly salt water and land forms. Along the shore are very dis-tinct traces of a rising of the land. Between the sea and the sandhills runs in part a higher level of sand, which must, in the not very remote parts, have been the beach washed by the water. In parts it is now being washed away by the waves, and shows a diminutive sand cliff, in whose section facing the sea are not only very distinct layers of comminuted shells similar to those now found along the beach, but also planks, now con-siderably above the reach of the water even at high tide.

Passing inland, we left the sandhills behind us, and went on to a plain lying to the north of a series of fresh-water lagoons, and known as the Reedy-flats. South of this are the lagoons and much swampy land, which is drained by streams which partly flow into the Yellow Rock Creek and partly lose themselves amongst the sandhills. Here by one or two members of our party eight living specimens of the large copper-headed snake (Hoplocephaina superhus) were captured, much to the mingled consternation and amusement of our guide, who soon became as zealous a collector of everything around as anyone of us. In more especially the swampy parts the ground was carpeted with a small variety of violet, and when we passed on to somewhat higher country we found ourselves in open land with abundance of the common bracken fern (Pteris aquiline), and here and there patches of the swamp ti-tree. Striking east we came into scrub land, and pursued our journey along a track in pouring rain, which, together with the scrub, made travelling difficult and very unpleasant, and we were soon thoroughly wet. Camping at midday beside a small lagoon, surrounded by reeds and ti-tree in blossom, we lit a fire, and tried to imagine that we were comfortable; we had fire and food, and things might have been worse. Before long we were on the tramp once more, passing through scrub land, with fern, ti-tree, acacia, banksia, currant tree, and oily bush, until we came to the shores of the Martha Lavinia lagoon. (Start HT 13687.2) This is a large sheet of water about one mile long by half a mile broad, the margin of which is formed of a peculiar and very striking white silver sand, which, surrounded by the dark green foliage and reeds, gives a very strange effect. Along the shores there was nothing for it but to wade through the water amongst the closely-packed bunches of reeds, mia-mia, and cutting grass, and for nearly a mile we had hard work to get along at all. At the east end of the lake we came to rising ground, cleared recently by fire, and further on, passing by the side of the lesser Martha Lavinia lagoon, and climbing up perhaps 200ft., we reached the top of the sandhills bounding the eastern shore of the island. Tired and soaked through to the skin, we had yet some eight miles to go before reaching our camping-ground for the night, and for half this distance our track lay along heavy loose sand. It was with thankful feelings that we reached a hut known as Bertie's camp, and pitching our tent, made a large fire, and despite weather and the fact that we had to sleep on ti-tree poles or 'long feathers', as they were called in camp, passed a most enjoyable evening and night. Next day we continued our southward track along Sea Elephant Bay until we reached the river of the same name. This is a stream of considerable size. It rises on the hilly country, covered with timber and impenetrable scrub, in the centre of the island, and flows to the sea over broad flat plains covered with the usual ti-tree and scrub. Its estuary is broad and shallow, and almost empty of water at low tide, whilst the black swan is plentiful. At its mouth, on the sandhills, a bird rare in these parts was taken, together with is eggs - the Caspain tern (Sterna Caspia). Crossing the stream we went still further south, and then, striking inland, reached our southernmost camp a few miles north of Fraser River. It was placed on the top of a hill commanding a fine view of the bay with its long range of hills covered with blue-gum tree forests on the south, whilst away to the east lay Sea Elephant of Councaller Island, the home of cormorants and gulls and mutton birds, all of which have rookeries on this small islet. Along the eastern coast are indications of raised beaches just as on the west, and there is a remarkable series of ranges of sandhills running parallel with the coast and now covered with scrub, in which wallaby and what the hunters call kangaroo is plentiful. We had the dogs with us, and caught as much as we could eat. The wallaby is the Halmatarus Billardieri of Tasmania, the kangaroo is the Il Bennetti, or the bush-kangaroo of Tasmania, both of these animals thus indicating a distinct alliance with the latter country rather than with Victoria. Various birds were shot during the day, the dusky robin of Tasmania, the dove-like prior (Prior turtur), the sooty oyster-catcher (Hæmatopus unicula), and the sacred kingfisher (Halcyon sanctus); whilst along the shore a variety of specimens of sponges, alcyonarians, and tunicates were obtained. At the camp the curious beetle known as the skin-eater by the hunters was found in abundance, and a considerable number of insects were taken.

(End Part I)

26th November, 1887

No. II

We explored as far as possible the east coast to the south of our camp, dividing into smaller parties, some going inland to the blackwood forests, some down to the Fraser River, one of the most picturesque spots on the island, and into the bluegum woods, and some further south still, along the coast, gradually getting more and more rocky until it passes into what is known as the 'Brick Wall,' where impenetrable forest comes down to cliffs of granite, against whose base the surf breaks with great strength.

Along the shore we found five echidnas or porcupines - the lowest and in some respects most interesting of mammalian. They are certainly mammalia, because they suckles their young, and yet not only is their skeleton, especially the shoulder girdle, distinctly reptilian in character, but they lay eggs just as reptiles do, and thus form a wonderful link, binding together two great divisions of the animal kingdom once thought perfectly distinct from one another - the reptilian and the mammalia.

As usual, the rock along the coast are mainly granite, though in one part, at the mouth of the Fraser River, there is an outcrop of sandstone, and close by, also a very loose soft rock, formed of a dark-coloured sand, composed apparently of minute rounded particles of quartz, held together by a dark black-coloured matrix. South of the Fraser River the country, instead of being open and covered with low-lying scrub, is clothes with luxuriant vegetation of blackwood, bluegum, acacias, musk, sassafras, &c., and it is curious to observe how completely the river forms a bounding line. North of the river for perhaps one to two miles inland are sandhills, formed by the gradual accumulation of the sand by the wind, and doubtless indicative of a gradual rising of the land.

The only game at all plentiful were the kangaroos and wallabies, though a few specimens of birds were taken, such as, in addition to others mentioned before, Pachycephala olivacea of Tasmania and Victoria, the Selby shrike thrush of Tasmania; and it was interesting to note that the echidnas were the hairy species of Tasmania, and not those of Victoria. Retracing our steps, and passing still further northwards, we came to the Wickham Lighthouse, and were most hospitably entertained by the superintendent, whose kindness, together with that of his assistants, we have to gratefully acknowledge. Both here and at the hunters' home members of our party were frequently entertained, and always met with the kindest reception. To the south of Wickham lies a large lagoon, hitherto known only by the name of the big lagoon. This we renamed Lake Dobson, in honour of Dr. Dobson, to whom the exploration party was much indebted for valuable assistance in various ways. Attempts had been made to dredge at Wickham, but after several hours' hard work, and after putting down the dredge some 30 times, and working over some three miles, it was given up as useless, the dredge bringing up nothing save sand. Operations of this kind were necessarily confined to the part in which a boat was procurable. After a rest in camp on Sunday, we started for the West Coast, taking this time three horses with us. It was our intention to press through in the day to Currie Harbour, as our time was getting short. The distance was only 26 miles, that is according to the hunters, but there was a prevalent idea amongst the members of our party that a mile on King Island was a variable quantity, never meaning less, and usually con-siderably more than a mile on the mainland. As far as Whistler's Point we went along the beach, and then struck inland over hilly country, with the usual scrub and fern, coming out on to the beach again after a few miles. The sandhills facing the sea are largely covered, as all over the island, with smoke-bush and pig-face (mesembryanthemum), the beautiful red flowers of which massed together form a striking feature in the land-scape, whilst not only here, but everywhere in the island, the poisonous tare, with its beautiful purple flower, grows in profusion. Along the shore in parts ducks were plentiful, with oyster-catchers, and Pacific and silver gulls and dotterels.

We crossed the Pass and Porky rivers, and then for the last eight miles our track lay inland, at first over hills covered with prairie grass and the native tobacco, then over rich-looking country covered with fern and showing here and there trunks of blue gum trees, and finally through dense scrub of swamp, ti-tree, acacia, bobyala, currant bush etc. In parts the track was very swampy, and the ground pierced with the holes of the boring crayfish, whilst here and there orchids were found, Calochalis Robertsonia, Pterostyliss barbata, Thelymnitra flexiosa, and the fern schizoa bifida. Emerging from the scrub we came to open ground, with fallen trunks of blue gum, and reached Currie Harbour, a small cover, fit only, owing to the number of reefs at its entrance, as a shelter for small craft. Here, as at Wickham, we, and other members of our party who had preceded us, were hospitably entertainment.

The coast here and to the south is formed by jutting promontories of granite and gneiss, weather worn into angular blocks, pieces of which are continually being broken off, rounded by the action of the water, and then thrown up to form a great shingly beach. About four miles south of the lighthouse lies British Admiral Bay called after the ill-fated vessel which struck upon the reef outside, and of which fragments still strew the shore. Photographs were taken here, as at many other points of historical and picturesque interest in the island. There are to be seen graves of two, amongst the 78 who were drowned - Daizell Nicholson and a young girl names Tilly Dale, whose tomb has been removed from its original position by the hunters, as the sea was washing away the sand bank in which she had first been buried. It is difficult to imagine a more inhospitable shore than this western coast of King Island, and it is most gratifying to find that since the erection of the Currie lighthouse, commanding the sea from Cataraque Point on the S, to New Year Islands on the N., not a single wreck has occurred, though there were no fewer than 21 recorded in the 20 previous years. Tramping on we reached the Etterick River, flowing through a narrow gorge, showing on its northern side an outcrop of schistose rock, not met with elsewhere. With regard to the geology of the island, there is little to be said, as our time was too limited to allow of close examination, and it was difficult to find any good sections. Over the whole surface, but with very few exceptions, there appears to run a strongly marked granite formation, some-times very coarsely at others very finely grained, and always grey in colour. Frequently, as just south of Wickham and at the Fitzmaurice Bluff, the granite passes gradually into gneiss, in which the plates of mica are of large size, and this gradual passing of the one into the other may take place within the space of 100 yards. It is this granite formation whose outcrops from the cliffs of the southern part, and the dangerous reefs lying close beneath the water all around the coast, and upon which even on the calmest day, the surf beats heavily. Resting upon this granite and dispersed widely over the whole surface of the island is a curious formation of limestone. Small outcrops can be seen coming to the surface amongst the scrub far inland, but in only a few spots does the limestone from anything like a cliff upon the shore. Just south of the Pass River, on the west coast, it appears for a very small space projecting through the sand, but only giving an indication that the formation exists, covered up by the sand blown from the shore by strong W. and S.W. winds. Its weathered surface is very friable, and only one small piece was obtained, containing fossils in the form of minute molluscs. In several parts of the island, and notably at a spot known as the Dripping Wells, about one mile south of Etterick River, occurs a curious and interesting formation, very frequently met with in limestone districts, the water, absorbing carbonic oxide from the air, comes in contact with the limestone, and containing the oxide in solution possesses the power of dissolving a certain amount of the carbonate of lime. Charged with this it flows away to the sea, and after a longer or shorter period, its contained carbonic oxide evaporating, it loses the power of retaining dissolved the lime. This then is deposited around any object with which the water comes in contact. In the case of the dripping wells, the streamlet, flowing down from the limestone districts upland, passes over granite rocks into the sea, and evaporating has left here a curious deposit of lime, now reaching the height of 20ft. to 30ft., and extending lengthwise for perhaps 150 yards. The upper part of the small cliff thus formed has gradually come to project beyond the lower part and thus small caves have been formed. From the roof of these water trickles slowly, and in doing so evaporates and leaves the lime behind to form a pendant stalactite ever increasing in size. From the pointed end of this the water falls to the ground, and here the same process repeating itself a stalagmite is formed gradually growing upwards as the stalactite grows downwards. In other parts the water containing lime in solution evaporates in contact with roots and stems of trees, and depositing particle for particle in their tissues, a complete representation of the latter is preserved. Such curious structures were found close to Yellow Rock, Pass River, and Boulder Point.

(END OF HT.13687.2)

(START of HT.13687.3)

One of our number, more enterprising than the rest, and well used to bush life, had already passed further south alone, and leaving Etterick River two more pressed on southward, whilst the remainder sought the tablet erected to the memory of the 483 who perished in the wreck of the Cataraque. Fitzmaurice Bay is bounded on the south by a high bluff of the same name running boldly out to sea. The passage round this is an extremely severe one, as the rocks are gneissic or granitic, and sharply jagged. The tide was high, and there was nothing for it but to jump from point to point, and chance the breaking of an odd limb or two. Amongst the rocks the smokebush and pigface (mesembryanthemum), with its two varieties - white and red - were growing in profusion, but the most striking feature was the great development of the wild geranium (pelargonium Australe), which grew in every nook and cranny. Running far out to sea the granite formed low-lying reefs, and turning the corner of the bluff we came upon a much wilder scene. The cliffs rose straight from the water, forming a long perspective of promontories, against which the surf was beating, sending clouds of white spray high up against their sides. The winds from the W. and S.W. were evidently too strong to allow the growth of anything but low scrubs and all the ti-tree and other scrub lay, as it were, flattened down upon the hillside. The scenery of this part was by far the wildest and most imposing seen upon the island. It was in this part, close by a granite mass standing alone in the sea, and known as the Seal Rock, that the solitary members of our party above referred to saw the only seal which was met with during our stay. He was not successful in capturing that animal.

Farther south than this it was not possible for any of us to penetrate, much as we should like to have done. Our stay upon the island was limited to little more than a fortnight. The weather, at all events at first, was very unpropitious, and our journeys were often carried on under great difficulties, penetrating dense scrub by paths not often used, passing through swamps and along soft, sandy beaches, laden more or less heavily, and this sometimes, as on our east coast journey, in pouring rain. An evening spent around a roaring camp fire, even though followed by a night with boughs of ti-tree for our bed, invariably restored us to activity, and now that the trip is over the pleasant parts - and they were very many - will be remembered, the unpleasant forgotten. On each occasion the whole party was divided into sections, some staying at the main camp and penetrating the country inland, passing north to Wickham and south to Currie, whilst the other division journeyed to the east coast, and the combined efforts of all parties resulted not perhaps in the acquisition of a great quantity of game, but in the securing of a considerable number of specimens of scientific value. At present it is possible only to name the birds, reptiles, and mammals, and a certain number of plants found upon the island, but in addition to these a vigorous search has been made for the lower forms of life - insects, molluscs, colenterata, ecainodermata, vermes - and a good collection has been brought together, particulars of which will be pub-lished as soon as the names of the forms obtained have been ascertained from the specialists to whom they will be handed over.

The last two days were spent quietly in camp, packing up and madding ready to depart, and on the evening of Saturday, November 19, the smoke of the Lady Loch was seen far away upon the horizon, and we felt that once more we were in touch with the civilised world, though possibly our personal appearances after a fort-night in the scrub was more that of wild than of civilised beings. Sunday morning broke calm and fine, with very little surf beating upon the shore, and under these circumstances Captain Anderson deemed it wise to take us on board at once. Three hours were occupied in taking down the tents and packing, and at 1 o'clock we steamed away to pass the night under shelter of the New Year Islands. These are two somewhat low-lying granite islands, the larger about one mile and a half in length, the lesser one mile, which lie some five miles to the west of King Island. They are the home of mutton birds, which here have their rookeries, though, curiously, no trace of mutton birds was seen upon King Island itself. Unfortunately for us, the time had not arrived for them to come upon the island to lay their eggs. One nest with eggs was found on November 20, but no more. It is curious to observe that they usually upon the 22nd-24th November, their approach being heralded by a storm, known as the mutton-bird gale. This over they arrive in crowds. Leaving early Monday morning the Lady Loch steamed away from the islands, and calling at Apollo Bay landed us at Williamstown late on Monday evening. So far the results of our expedition may be summed up almost in one word. Naturally as well as politically, King Island belongs to Tasmania and not Victoria. In the past history of the earth's of the earth's surface it seems as if the large Australian continent had split into two portions, one com-prising Australia proper, the other Tasmania and the islands (certainly King Island) between it and Australia. In this small division certain peculiar varieties of animals, and doubtless of plants, arose before King Island separated from Tasmania; and hence it is that, at the present time, we find the two latter agreeing so closely in their indigenous fauna; indeed, in King Island there only occurs, so far as the present expedition has been able to ascertain, one single species of bird (Sisticola ruficapa) peculiar to Victoria and not occurring in Tasmania. There is no doubt that such expeditions as the present one are of great service, not only to science but in affording valuable experience to some of its members, who may in aftertimes undertake the exploration of unknown lands. It would be impossible not mention gratefully the kindness received by the expedition from Captain Anderson and the officers and crew of the Lady Loch in our passage to and from the island, and the hospitable treatment experienced by the various parties who visited the Wickham and Currie lighthouses; from all these, and from our guide, Henry Grave, we received every assistance, always cheerfully given, in our work.

...the principal vertebrate animals found upon the island:-

MAMMALIA

AVES

REPTILIA

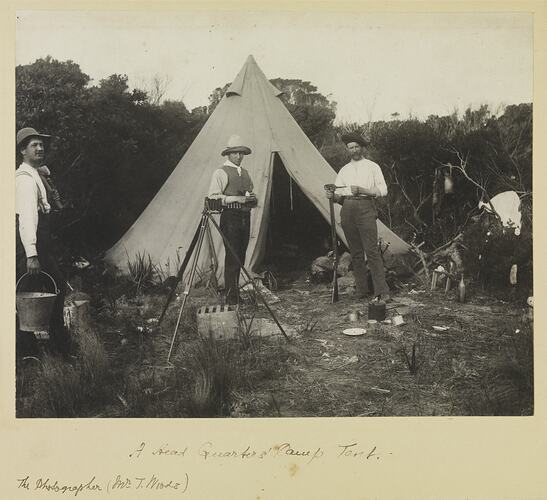

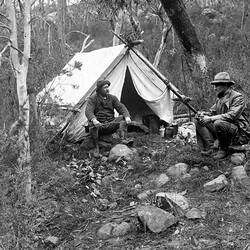

PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN

Five camp views

Five views of the marsh

The landing from the Lady Loch

*Wreck of Abeoria (?), showing Sea Elephant By

Blackwood and blue-gum forest, East Coast

Encampment at Spencer's Creek

Lake Dobson

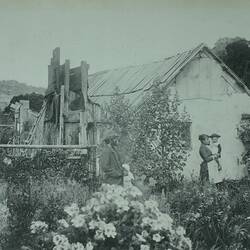

Hunter's home

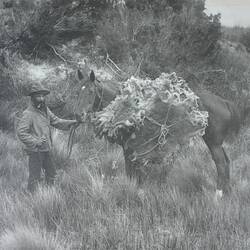

Hunter and horse

Group of expedition, with Captain Anderson and some of the crew of Lady Loch

Mouth of Fraser River

Lesser Martha Lavinia Lagoon

Cape Wickham Lighthouse, &c.

Wreck of Ocean Bride, with New Year Islands in distance

Wreck of Arrow

Currie Harbour, lighthouse, &c.

Tombstone in memory of those drowned in British Admiral

Cataraque tablet in *Eitamanrine Bay

Fitzmaurice Bay, with Bluff

Dripping wells

Lady Loch off New Year Islands

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types