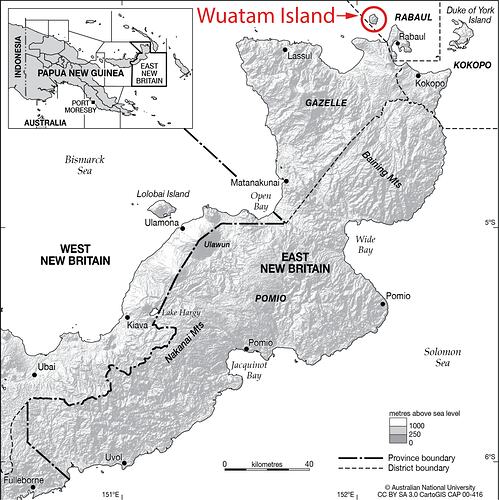

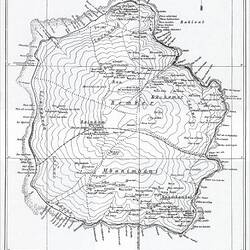

Wuatam (Watom) Island is situated a few kilometres off the north coast of New Britain in Papua New Guinea. The 4.5 km-long island has been occupied by the Gunantuna (Tolai) people for many generations. Various dialects exist within the Tolai language, which is called A Tinata Tuna (Kuanua). Wuatam Island has its own distinct dialect of Kuanua, which is closely related to a dialect spoken on the north coast of East New Britain.

Their discovery, antiquity and local meanings

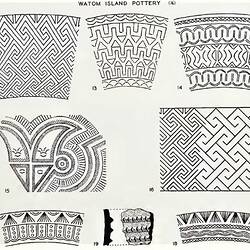

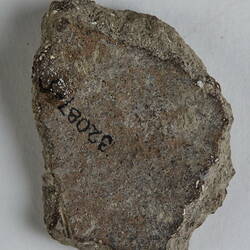

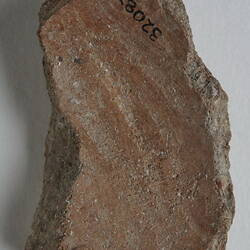

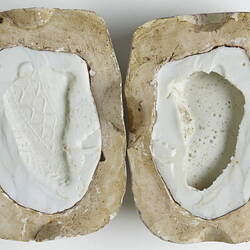

In 1909, several small, intricately decorated earthenware pottery sherds were found eroding from the ground near the coastal village of Rakival. A German missionary - Otto Meyer - conducted amateur excavations near the discovery, which revealed deep deposits containing similar sherds (up to two metres below the surface). Examples of the fragmented pottery were sent to museums in Basel, Berlin, Cologne and Paris as well as to Australia. Museums Victoria cares for 27 of the Wuatam Island pottery sherds, which have been on long-term loan from the Australian War Museum since 1925.

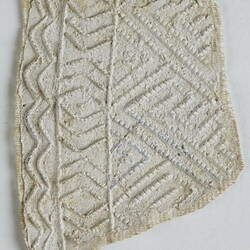

Otto Meyer sought the advice of Wuatam Islanders about the origins of the pottery and the meaning of the decorations. In a short article written for the journal Anthropos, Meyer recorded that locals told him: 'the designs ... were probably made by Pir'. Pir means story or legend, and is derived from the name of a legendary person in Wuatam Islanders' tales. Wuatam Islanders had names for two of the designs: Tutumu and Daudaul. Tutumu means 'written' or 'a piece of writing'.

The results of more recent archaeological excavations on Wuatam Island suggest that the pottery deposits date to sometime between 2850 and 1850 years ago. The sherds at Museums Victoria feature remarkable geometric and figurative patterns, which the potters would have incised or stamped onto the clay before firing using various tools (such as combs).

Pot sherds with similar designs have been found at the oldest archaeological sites in Vanuatu, Fiji, New Caledonia, Tonga and the south-east Solomon Islands. They have also been found in other island and coastal locations in northern and northeast Papua New Guinea, as well as on the south coast near the nation's capital (Port Moresby). The pottery - called 'Lapita' by archaeologists - was made by seafaring First Peoples who established their homes in these locations between approximately 3300 and 2550 years ago.

Contemporary connections

The expert seafarers who made the pottery are among the ancestors of Micronesian, Polynesian and some Melanesian communities. The pottery is highly culturally significant for many Pacific Peoples today. Images of the decorated sherds are used today as national symbols in Fiji, the Solomon Islands and Vanuatu (featuring on postage stamps, for example). The pots, and the expert seafaring peoples who made them, connected and continue to connect people and places across the Pacific.

There are many pottery practices that have shaped, and continue to shape the history of the several hundred cultural groups of Papua New Guinea. Customarily, earthenware pots were used to cook food and store water. Mary Gole, an Orokaivan woman from Oro Province, continues the age-old custom of pot making, which only women in her clan can practice. Mary makes contemporary pots with designs often featuring female faces, to honour the incredible contribution of Papua New Guinean women to family livelihood.

In the Port Moresby region of Papua New Guinea, Motu women use dance to speak of the pottery they made for the seagoing Hiri trade, which involved exchanging the pots with people living in the Gulf of Papua hundreds of kilometres to the west. Arms stretched above their heads, they shape their hands around an earthenware bowl while swishing their woven fibre skirts. Motu women's dance movements celebrate the history of the Hiri trade, which was practised up until the 1950s. The dances are performed each year as part of the Hiri Moale festival.

Bougainville artist Taloi Havini learned the sacred practice of traditional pottery from Tamana Sarenga, a master potter from Malasang village on Buka Island. Today Taloi uses clay and porcelain to create contemporary forms, for example making Beroana, which is a local shell currency in Bougainville.

Papua New Guinean people today continue to fulfil the philosophies of Bernard Narakobi: 'Like the fruits of our mother earth, we, the potters and the weavers, can and should shape our own history'.

Further reading

Anson, D., Walter, R. & Green R.C. 2005. A revised and redated event phase sequence for the Reber-Rakival Lapita site, Watom Island, East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea. University of Otago Studies in Prehistoric Anthropology 20. University of Otago, Dunedin.

Casey, D.A. 1936. Pottery from Watom Island, Territory of New Guinea, ethnological notes. Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria 9:90-97.

Dotte-Sarout, E. & H. Howes. 2019. Lapita before Lapita: the early story of the Meyer/O'Reilly Watom Island archaeological collection. The Journal of Pacific History 54(3):354-378.

Green, R.C. 1998. An introduction to investigations on Watom Island, Papua New Guinea. New Zealand Journal of Archaeology 20:5-27.

McDougall, R. 2016. Mary Gole interview, in No. 1 Neighbour: Art in Papua New Guinea 1966-2016. Queensland Art Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. p. 108.

McDougall, R. 2016. Taloi Havini interview, in No. 1 Neighbour: Art in Papua New Guinea 1966-2016. Queensland Art Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane. p. 112.

Meyer, O. 1909. Funde prähistorischer Töpferei und Steinmesser auf Vuatom, Bismarck Archipel. Anthropos 4:251-252.

Narakobi, B. 1980 (revised 1983). The Melanesian Way. Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies and the Institute of Pacific Studies, Suva. p. 5.

Specht, J. 1968. Preliminary report of excavations on Watom Island. The Journal of the Polynesian Society 77(2):117-134.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types