Diphtheria is an infectitious bacterial disease caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. It first spread across the world in 1856-58, identified as a new disease although it had probably first appeared at least a century earlier. It was one of the first diseases to be identified as an infectious microbe (in 1883), readily identifiable under a microscope. Typically a childhood disease, it causes inflammation of the throat and sufferers sometimes, although not always, develop a mucous membrane across the throat. A form can also manifest on the skin. It was a major cause of childhood mortality.

In response to the 'ravages of diphtheria in Victoria', a Royal Commission of Inquiry into Diphtheria was held by the Victorian government in 1872. The enquiry's findings included that it afflicted rich and poor alike; that living on high ground was not protective; hygiene was a factor in its spread; it was highly contagious; and it could be caught more than once. Sulphur was recommended for every household as a disinfectant. In 1894 antitoxin therapy became available, but a vaccine was not readily available until the 1920s.

In 1890 morbidity in Victoria was 92.11 per 100,000, falling to 14.51 per 100,000 by 1900, but it continued to be a significant scourge. In 1912, 59 schools in Victoria were closed between one week and one month because of outbreaks of diphtheria. (G. Halley, 'Diphtheria as a school problem', Health, 1923: 64-5, cited in Hooker & Bashford). In 1919 the Health Act in Victoria was one of many pieces of legislation passed in Australia to enable government agents and medical specialists to treat known carriers as if they were actually ill, and therefore subject them to quarantine measures.

A typical report in 1921 from Swan Hill doctor recorded that 134 school swabs were taken, and 290 of their contacts were also swabbed. State and Sunday schools were closed for three weeks, after which recovered patients had to be re-swabbed before being allowed back to school. (F R Legge, 'Prevention of diphtheria', Med. J. Aust., 1918, i: 391; 'Prevention of diphtheria', Med J. Aust., 1921, ii: 417, cited in Hooker & Bashford).

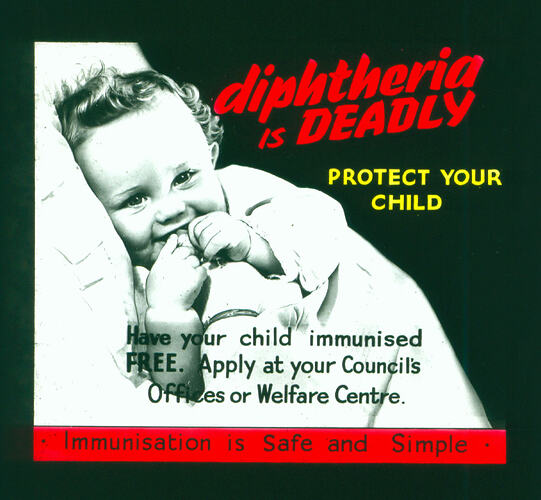

In 1918 the Medical Journal of Australia recommended swabbing to identify bacilli, isolating those infected and waiting for the disease to die out. But the editor noted that ' it would be utopian to expect the State Governments to sanction the expenditure necessary to control the faeces of the whole community. Much, however, can be accomplished by a methodical search for carriers in the environment of every notified case.' (The prevention of diphtheria', Med J. Aust., 1918, i: pp. 90-1, cited in Hooker & Bashford). Vaccines were available but there was concern they would not be accepted by enough people: public mistrust, the fact that diphtheria impacted children rather than adults and the lack machinery for large-scale implementation were also barriers.

With the broadening use of vaccinations, diphtheria became a decreasing problem in Victoria during the 20th century. It is rarely seen in Victoria today.

References

Hooker, C., and Bashford, A. (2002), 'Diphtheria and Australian Public Health: Bacteriology and its complex applications, c.1890-1930', Medical History, 46: 41-64.

1872 'TUESDAY, JANUARY 16, 1872.', The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), 16 January, p. 4. , viewed 02 May 2020, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article5858826.

Diphtheria: Report of the Royal Commission, 1872.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Localities

-

Authors

-

Article types