Summary

Alternative Name(s): Recipe Book, Cookery Book

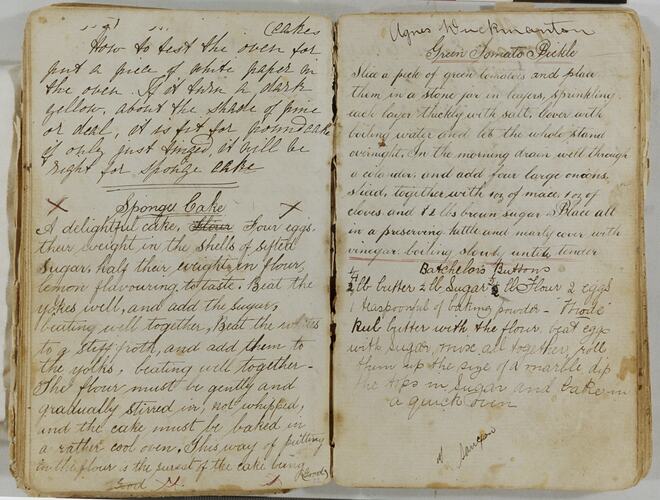

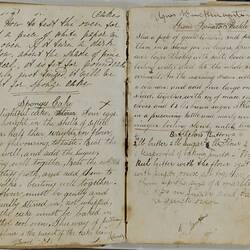

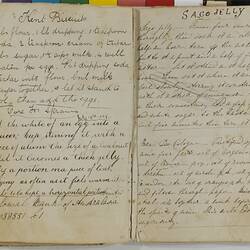

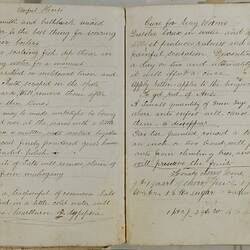

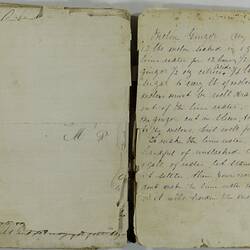

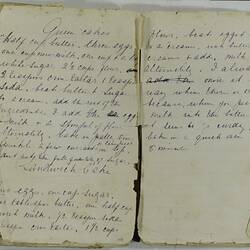

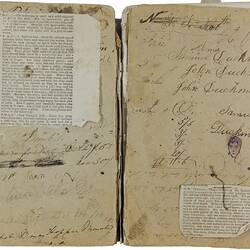

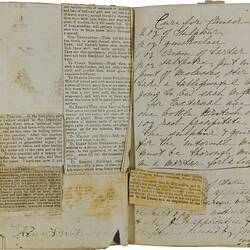

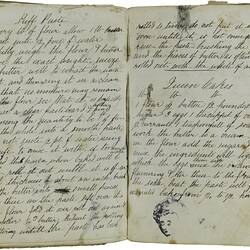

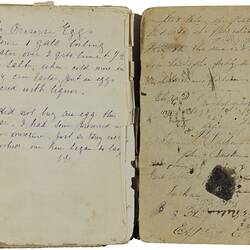

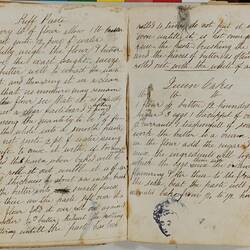

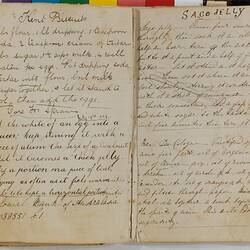

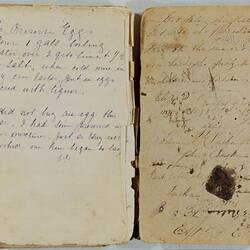

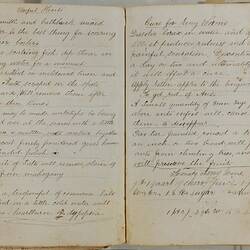

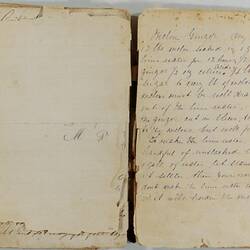

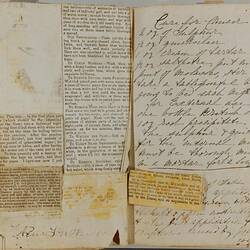

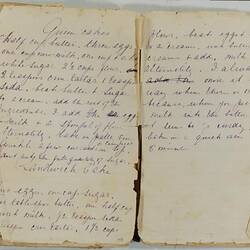

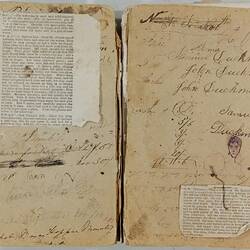

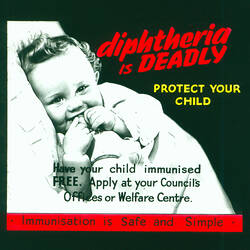

Book titled 'Recipe & Remedy', written and compiled by Eliza Duckmanton in 1870. The book contains recipes and remedies hand-written in pen, and cuttings pasted in from other publications. Recipes for cakes and biscuits predominate, with recipes for jams, jellies, relishes and sauces similar to those used today. There are almost no savoury recipes, other than for relishes or pickles; and there is no mention of any Indigenous ingredients, unlike some of the first cookery books published in Australia. The book also contains a variety of remedies for relieving everything from sore throats to cholera and cancer.

Eliza Duckmanton (nee Womersley) was born in Nottinghamshire, England in 1843, and migrated to Australia around 1859. In 1862 she married John Duckmanton at Dunkeld in Victoria. The couple had 13 children, and Eliza became a bush nurse in the Dunkeld area. John was a carpenter and wheelwright, and constructed buildings in Dunkeld including the first state school. He died in 1915, at the age of 75, described as the 'beloved husband of Eliza Duckmanton' (The Age, 15 May 1915, p.5). Eliza was left with six adult daughters and six sons, one of whom was a soldier on his way to the front. (Hamilton Spectator, 20 May 1915, p.4). Sadly, Leo Duckmanton was killed in France in May 1917. (Eliza Duckmanton's story has many parallels with that of Eliza Amery, also told in Museums Victoria's collection.)

Eliza died on 27 September 1924, at the age of 81. Her book was handed down within the Duckmanton family until it was donated to Museums Victoria in 2002.

Physical Description

142-page book with brown cardboard cover with embossed pattern around edges. Pages of book are lined and contain recipes and remedies hand-written in pen, and adhered cuttings from other publications. Page numbers have been written in the bottom right hand corner of every second page. On page 14 there is a cutting that has come unstuck in the bottom right hand corner. Between pages 70-71 there are 3 loose pieces of paper. Between pages 110-111 there is a loose piece of paper. The last three pages of the book are not attached.

Significance

It was common for literate colonial women to create their own household management guides to suit their new country. Hand-written recipe books were sometimes even part of a bride's trousseau. This was because few cookery and household management books were available in Australia until the 1890s, and those that did exist were more suitable for English ingredients and kitchen facilities, being either imported from England or being locally produced imitations. Mrs Beeton's 1861 Book of Household Management was one of these; recipes were also published in imported magazines. Cookbooks were also usually aimed at city dwellers rather than country women, who had far less access to many ingredients. [Symons, p. 52-5 Gollan, p. 45-46] Further, many recipe books were written for experienced cooks - not for young middle class women unaccustomed to cooking. [Daunton et al p. 24]

Locally, home cooks could take advantage of recipe suggestions such as those by Caroline Chisholm in the 1850s. [Gollan, p. 45-46]. Others still relied on the age-old tradition of learning recipes by experience and passing them on through word of mouth.

Not surprisingly, the solution to this lack of guidance in the kitchen was for immigrant women to make their own recipe books, bringing with them to their new country the housekeeping expertise handed on by their mother, relatives and friends, and adding to it whatever experience they gained in the new colony, and whatever recipes and hints were passed on by other women who had met and mastered some of the new problems before them. [Gollan, p. 45]

The tradition of making and using home made recipe and remedy books continued until recently - indeed many of us remember our mothers valuing such recipe and remedy books. The recent explosion of commercially published cook books has caused the home-made book to largely, although not completely, lose currency. Not many of the early colonial home made recipe books survive in library or museum collections. This particular example provides a rare insight into the domestic life of a rural woman in the late 19th century and, as such, is a significant historical artefact.

More Information

-

Collecting Areas

-

Acquisition Information

Donation from Ms Kim Meredith, 20 Jun 2002

-

Maker

-

Classification

-

Category

-

Discipline

-

Type of item

-

Overall Dimensions

18.5 cm (Length), 12.5 cm (Width), 2.2 cm (Height)

-

References

Pioneer Families in Victoria, [Link 1] accessed 25 February 2011 MV Blog - Queen Cakes, [Link 2] Death of John Duckmanton: 1915 'Family Notices', The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954), 15 May, p. 5. , viewed 03 Jul 2025, [Link 3] See also 1915 'THE LATE MR. JOHN DUCKMANTON.', Hamilton Spectator (Vic. : 1870 - 1918), 20 May, p. 4. , viewed 03 Jul 2025, [Link 4] Death of Leo Duckmanton in World War I: 1917 '[?] [?]or', Hamilton Spectator (Vic. : 1870 - 1918), 1 June, p. 2. , viewed 03 Jul 2025, [Link 5] Death of Eliza Duckmanton: 1924 'Family Notices', The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957), 1 October, p. 11. , viewed 03 Jul 2025, [Link 6] Gough family tree, accessed on Ancestry, 3/7/2025.

-

Keywords

Cooking, Food Preparation, Healthcare & Medicine, Recipes, Remedies, Cholera