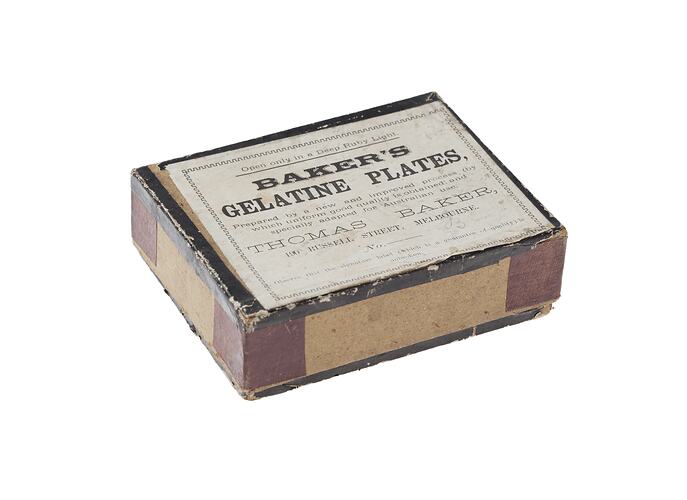

Thomas Baker's Gelatine Plates

It is 1884, and three people are hard at work in the darkened, underground cellar of their home by the Yarra River in Abbotsford, Melbourne. Guided by a dim, ruby red light, they are coating glass plates by hand with a silver gelatine photographic emulsion, to create dry plate negatives for photographers to use.

This was the beginnings of one of Australia's earliest dry plate makers - who were to become the most successful photographic manufacturing company in the country.

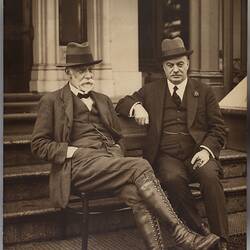

The trio in the cellar were Thomas Baker, assisted by his wife Alice, and her sister Eleanor Shaw. Thomas was the entrepreneur and the scientist heading up this venture.

Dry Plate Revolution

Dry plates had revolutionised photography in the late 19th century by making it more convenient and accessible. Invented in 1871 by Richard Maddox in England, dry plates superseded wet plates, which had to be prepared by photographers on the spot when taking a photograph and developed immediately with a mobile darkroom. With dry plates, photographers no longer needed to be experts at chemistry. They could now just buy the product off the shelf ahead of time, place it in their camera, take a photograph and then return to a photographic store to have the plate developed and a photograph printed from it.

The first Australian made plates were produced in August 1880 by Phillip Marchant of Adelaide, who sold his product as Adelaide Instantaneous Dry Plates. However, in the early 1880s the dry plates available in Australia were mostly imported, and the quality wasn't always reliable. Thomas Baker saw a gap in the market, and being a trained chemist, decided to pursue a manufacturing career in the rapidly expanding field of photography. Because of his chemistry expertise he was able to develop a successful product designed for Australian conditions, to compete with the imported brands.

Entrepreneur

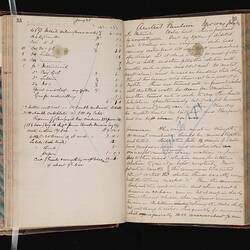

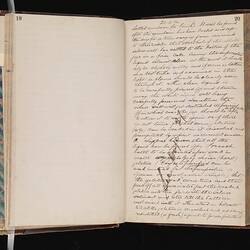

Thomas Baker first experimented with making photographic dry plates in the early 1880s. He painstakingly recorded his emulsion recipes, and the results of his many experiments, in a formulae book, which he kept in use for almost 40 years. Then in 1884, at age thirty, rather than continue his recently begun medical studies, he established a business to commercially manufacture these glass plates, which he branded 'Baker's Gelatine Plates'.

By 1885 Baker, his wife and his sister-in-law were selling his glass plate negatives to photographers at a shop that was located at 190 Russell Street in Melbourne. Kodak legend has it that they worked around the clock, making the plates at night and selling the plates during the day. In June 1885, Thomas Baker advertised for a messenger boy to assist at the Russell Street premises.

The emergence of dry plate photography in the 1870s provided immense opportunities for entrepreneurs like Baker. The most famous photographic entrepreneur was George Eastman, the founder of the Eastman Kodak company, who had started making dry plates in the USA in April 1880 and whose business had quickly become a huge worldwide success. Baker was only a few years behind Eastman with his Australian dry plate venture, and Baker and Eastman were later to get to know each other very well. Baker acted as an agent for Eastman products in the late 1880s, before going into business with him in the first decade of the 20th century.

From Family Cellar to Factory

Baker's business was a true cottage industry in the beginning, because he conducted experiments and made dry plates at his home, 'Yarra Grange'. This was a large bluestone house located on a former grazing property of about 7 acres along the Yarra River, across the road from Studley Park.

After its humble beginnings in the cellar of 'Yarra Grange', the dry plate business soon outgrew the Baker's family home. In mid-1885 Thomas Baker referred to his Russell Street premises as the 'Dry Plate Works', suggesting that he was making plates there and not at his home any more. However, that same year Baker must have decided that the business needed a dedicated manufacturing plant with room for expansion, and the property surrounding the Baker's Abbotsford home was gradually transformed into a complex factory site.

By 1886 Baker had constructed a small, yet grand, industrial building adjacent to his house, to industrialise his plate production. Called the Austral Laboratory, it was a three-storey brick building which accommodated Baker and his staff. While not much is known about his employees in this period, Baker is thought to have employed around ten people throughout the 1880s.

In this same year, 1886, Baker was granted a patent for "an improved method of, and apparatus for, drying photographic plates". 1886 was truly a busy and successful year for Baker, who also exhibited 'photographic sensitised materials and accessories' at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London, winning a Silver Medal.

Baker gained a reputation for making quality photographic negative plates. In January 1887, Baker's 'extra rapid' plates were used by Messrs. Kerry and Jones to take six photos at a Randwick race meeting. The exposures were estimated to have been lower than "one-thousandth part of a second" and were submitted to the Turf Talk column of the Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, who found them very interesting. In June 1887 it was noted by the Ballarat Amateur Photographic Society that their members used, among other brands, Thomas Baker's "specially rapid" and "No.2" dry plates.

In 1887 Thomas Baker registered a new trademark for his business, 'Austral', featuring the stars of the Southern Cross, which became a well-known brand for his products into the 20th century.

Exciting Developments

After three years in business, Baker's business took a new, exciting turn. In 1887 Thomas Baker established a new company with accountant and retailing whizz John Joseph (JJ) Rouse, known as Baker & Rouse. Baker & Rouse sold imported and local photographic products, including Baker's own products.

Baker created a separate manufacturing company, T. Baker & Company, which continued to make photographic goods, but operated independently to Baker & Rouse, with no financial connection between them until 1896 when the two companies merged to form Baker & Rouse Limited. Baker & Rouse went on to dominate Australia's photographic market for the next 21 years.

In 1908, 24 years after the first dry plates were made in the Bakers' cellar, Baker & Rouse merged with George Eastman's Kodak company to become Australian Kodak Limited. Later known as Kodak Australasia Pty Ltd, this Kodak company went on to produce photographic products in Australia for almost 100 years.

References

Australasian Photo-Review, Vol.58 No.12, 1 December 1951, p.748.

Ballarat Star, 30 June 1887, p.4.

Beale, N., History of Kodak, (no date), pp.3,5,13, Museums Victoria collection.

Britannica.com, Richard Leach Maddox | English physician | Britannica and Dry plate | photography | Britannica accessed 1 June 2021.

Government Gazette Victoria, 3 Sep 1886, p.2559; 23 Sep 1887, p.2821.

Kodak Australasia Pty. Ltd., Milestones in the history of Kodak (Australasia) Pty Ltd, Coburg, 1985.

Leader, 1 Jan 1901, p.104

Leggio, Angeletta, 'A History of Australia's Kodak Manufacturing Plant', Presented at the 2007 Joint PMG/ICOM-CC WGPM Meeting, Rochester, New York, Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume 12, Article 13, 2007, pp. 67-73

Museums Victoria Collection, HT 33863, Formulae Book - Thomas Baker, Austral Plate Company & Kodak Australasia Pty Ltd, Abbotsford, Victoria, 1884-1921

Museums Victoria Collection, HT 30096, Booklet - 'Around the Old 'Yarra Grange' Homestead...', Kodak Australasia Pty Ltd, Jan 1948, p.5, Museums Victoria

Museums Victoria Collection, MM 137963, Glass Negative - Baker & Rouse Pty Ltd, Austral Laboratory at Yarra Grange, Abbotsford, circa 1890, Museums Victoria

Noye, RJ 'Bob'. 'Philip J Marchant', Photohistory SA, accessed 4 June 2021, http://noye.agsa.sa.gov.au/Photogs/Phot_set.htm

Sands & McDougall Directory, 1885 - 1908

Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 8 January 1887, p.88

The Age, 23 Aug 1895 p.7; 15 April 1887, p.8; Age, 2 June 1885, p1

The Argus, 22 September 1886, page 6.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types

![Box - T. Baker & Co., Austral 'Ordinary' Dry Plate', Austral Laboratory, Melbourne, 1887-1896 [empty]](/content/media/31/1195281-thumbnail.jpg)