Summary

Celebrations of Victorian state identity and citizenship are present throughout the Museum collections. Occasions such as the 1951 centenary invited Victorians to both celebrate and reconsider their beliefs about what it meant to be Victorian.

Introduction:

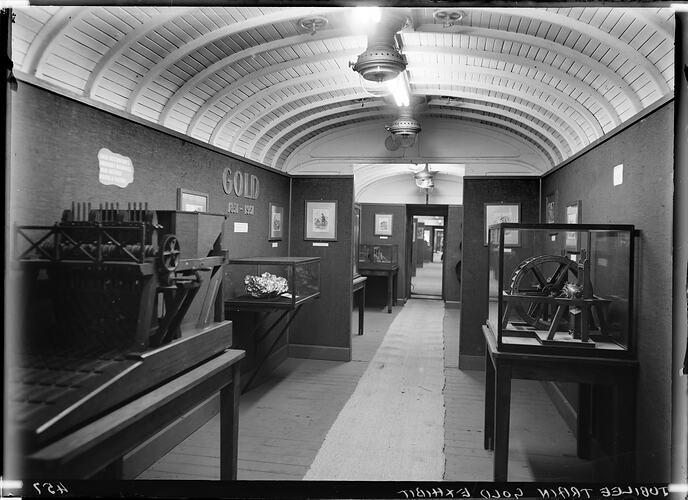

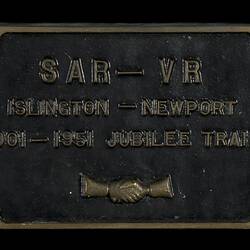

In 1951, a refurbished Red Cross train filled with Australian art, informative displays, and miniature models criss-crossed its way across Victoria. This was the 1951 Centenary and Jubilee Train, a moving exhibition space designed to bring the museum and gallery experience to regional Victoria. The Victorian train was one of several exhibition trains that toured Australia's states as part of the centenary celebrations.

Over the course of five months, the Victorian train completed four tours, from Werribee to Bacchus Marsh, Dandenong to Trafalgar, Healesville to Elmore, and Cheltenham to Lismore. A joint initiative of the Victorian and Commonwealth governments, the train was designed to bring people together to celebrate 50 years since Federation and 100 years of Victoria as an independent colony.

While other Australian states celebrated the national jubilee, Victorians embraced their state pride through a wide variety of events including sporting matches, marching bands, shearing displays, and barbecues. Events as wide ranging as a bed-making relay by Girl Guides and a greasy pig race in Castlemaine all had one theme in common - the public celebration of the Victorian community. The majority of celebrations followed a particular narrative of state progress that began with only a brief mention of First Nations people before colonisation then quickly moved on to a triumphal story of white Australian explorers, land development, settlement, and finally the growth of government and infrastructure.

The Train:

In reflecting on the centenary, the Jubilee Train brochure celebrated Victoria's enterprise as 'a true reflex of the indomitable spirit and breadth of vision of leaders of to-day and yesterday . and of a courageous citizenry, that have made Victoria great and will keep her so.' There were 28 displays spread through ten carriages, on themes ranging from the armed forces, infrastructure and agriculture, to art and literature, citizenship and community development.

The main Exhibit Train was accompanied by a secondary Entertainment Unit, headlined by comedian Jenny Howard who was supported by musicians, magicians, and a ventriloquist. In towns where the train stopped overnight, the Entertainment Unit would put on concerts described in the May 7th issue of The Riverine Herald as 'one of the finest variety programs' that was 'as good as the best in Melbourne any day.'

As it passed through towns, the train would stop at most stations for several hours or overnight to allow locals to view the exhibits. A visit from the Jubilee Train was a great occasion for most towns on the route, an acknowledgement of status and reason for a town celebration. Many towns visited by the train on a weekday gave school students a full or half day off so they could visit, and the train would often be greeted by thousands waiting to walk through the exhibits. At large towns like Ballarat or Shepparton, visitors could reach up to 11,000 over two days.

There were tensions, however, that underpinned the celebrations. There was an underlying uncertainty about what the celebrations were really for - and which national identity they were really celebrating. British? Or something uniquely Australian? There was also the issue of the violent nature of colonisation, a topic that was masked by the overarching emphasis on settler progress. While the celebrations aimed to foster community, this community did not make space for all Australians.

A Changing Identity:

Two exhibitions that demonstrated the tensions between Australian identities were the "New Australians" display and the art carriages. In the art carriage, artists following a European/British tradition were placed in conversation with those illustrating a newer (white) Australian modern style. Paintings were chosen that represented a 'cross-section of Victorian painting from the National Gallery Collections'. In particular, the curators put 'special emphasis on the more unfamiliar works of the younger painters.' The chosen artists included high profile male artists: Arthur Streeton, Frederick McCubbin, Tom Roberts, Hugh Ramsay, Rupert Bunny, Max Meldrum, James Quinn, Arnold Shore, and William Frater, as well as some unnamed 'contemporary painters'.

The Yallourn Live Wire praised how such choices showed 'the influence and tradition of Australian painting, while the break with this tradition is revealed by the work of more modern painters'. However, this so-called 'cross-section' of painting was very limited, with no Indigenous artists and no female artists listed in the commemorative booklet. B. E. Carthew from the Portland Guardian lamented that there was not 'one painting by the Aboriginal [artist Albert] Namitjira [sic].'

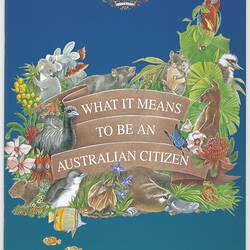

The Immigration carriage was praised by the Portland Guardian as 'wonderfully conceived'. Displays presented dolls in different cultural dress and maps of migrant origins. This exhibit was intended to encourage the 'assimilation' of the 460,000 European migrants who arrived in Australia in the previous three years. The Portland Guardian quoted PM Robert Menzies' opening statement at the 1950 Australian Citizenship Convention and reflected that if 'everyone in Australia understood that migration was vital to our existence, growth and development, then we should regard every migrant as our friend and we should go to no end of trouble to make every migrant feel at home.'

These messages were confirmed by the Australian government's pamphlet, Why Migration is Vital to You, which was distributed in the thousands via the train. It urged Australian citizens to approach migrants 'sympathetically', and help them 'to qualify for all the privileges and responsibilities of full citizenship.' Visitors to the train were urged to learn from migrant 'traditions' and 'ancient cultures', which can 'impact our culture. can mature it and bring to it the traditions and skills which we might otherwise take centuries to discover.' Yet the government's brochure also alluded to a source of tension and uncertainty around European migration in this exclusive era of 'white Australia', reassuring readers: 'We shall remain a British community with nine-tenths of our people of British origin.'

To encourage children to engage with the train, there was a statewide essay competition on what Victorian students had learnt from the train. Winning entries that were published in local newspapers reflected the changing nature of the Victorian population. Junior Section winner from Trafalgar South, Dorothy Kemp, wrote that she had learnt 'many migrants have come to Victoria in recent years, who are a big help to industries and farming.' Yallourn High School Senior Section winner Beverley Joan Gregory similarly picked up on how the 'migrants from many European countries.pouring into the State' were central to developing industry.

Tens of thousands of Victorians saw the train as it made its way across the state, bringing culture and community to those who found it hard to visit Melbourne. Yet in celebrating community and progress, the moving exhibition offered a conflicting vision of Victorian history which struggled to reflect the changing nature of Victorian society.

Dr Hannah Viney is a historian based at Monash University.

Prof Melissa Miles is an art historian based at Monash University.

Further Resources:

Jessie Mitchell, 'Maypoles and electric fences: centenary celebrations in 1950s Victoria,' Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society 96, no. 1 (2010): 80.

This work was produced as part of the Australian Research Council funded Discovery Project 'Envisaging Citizenship: Australian Histories and Global Connections' (DP200100088) https://picturing-citizenship.org/

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types