Born in Budapest, Hungary in 1900, Andor moved to Vienna in 1919 with his family, where he studied sculpture and modelling. Moving to Paris to study art, he met Picasso and was influenced by the works of contemporary artists including Matisse and Modigliani. Andor experimented with but ultimately rejected cubist and abstract styles in favour of a classical interpretation that would become his hallmark in the coming years. In 1924 he returned to Vienna to complete his architectural studies. Graduating in 1927, he returned to Budapest and became a student of Hungarian sculptor and medalist Ede Telcs. For the next ten years they worked together on commissions, with Andor focusing on how the sculptures integrated with the architectural requirements of their clients.

Andor married Elizabeth Bakk in 1932 and three years later their first son was born. In 1939, anticipating the war, Andor moved to Australia with his family. Classed as an enemy alien, he struggled to find an entrance to the Australian art world. His solution was to approach leading figures in the academic, medical and religious communities of Melbourne, offering to produce medallic portraits on approval; if the sitter did not like the results, there would be no charge. Within two years he had completed 41 medals, only one of which was rejected. Portraits of University of Melbourne senior academics, including John Medley, were among his earliest commissions. Andor became a familiar sight at the university, 'a lean, muscular man, with a deeply lined face and a shock of unruly hair kept in place by a tight-fitting beret, striding about the campus.'

His larger pieces received a mixed reaction. The King George V Memorial Hospital for Mothers and Babies in Sydney commissioned three works from him. The 'Statue to Maternity' (1944), carried out on a monumental scale with his wife Elizabeth as the model, received the greatest public approval, and medals based on the sculpture were bought by new parents. His other two sculptures for the hospital - portrayals of both a surgeon (1945) and King George V (1946) as human beings beset by human doubt and weakness - challenged the tradition of heroic portraiture and the initial public response was less enthusiastic. Today they are considered to be an important element of the hospital's reputation as an iconic modern building.

Discouraged by the reception of his larger works, and struggling to establish a reputation in a country without an established medal tradition, Andor left Australia in 1949. He undertook sculpture work at Canterbury, England, and was commissioned to complete a medal series depicting the Stations of the Cross, a project on which he had been working for seven years. It would take him another 20 years to finish the 14 medals of the 'Canterbury Series'.

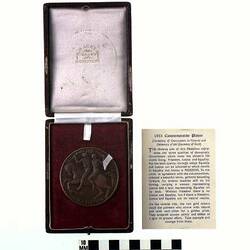

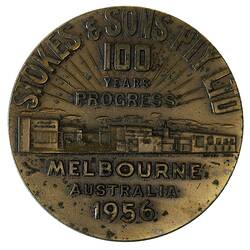

England appeared no more promising than Australia in terms of sculpture commissions, so he returned to Melbourne in 1950. Over the years he produced a number of large-scale sculptures, but it was in the creation of medals that he cemented his reputation. With the influx of post-war European migrants, and the flowering in Australia of a new cosmopolitanism, Andor's skill in the medallic tradition began to be fully appreciated. He produced more than 1000 medals in his lifetime, but it was perhaps the commission to create a medal for the 1956 Olympic Games that brought him fully into public acceptance. There were several variations of this medal with different purposes, including for cultural contributions. Andor had organised an art exhibition in conjunction with the Games, and it was with a sense of irony that he accepted one of his own medals in recognition of his efforts!

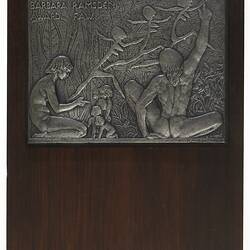

He said of his medals that they were 'the chamber music of the pictorial arts', and a review of an exhibition in 1971 commented that his work 'represented a most masterly handling of a rare form of art which few others can touch with the same extraordinary finesse and artistic judgement.' He was, however, regarded in most contemporary art circles as an anachronism, with his insistence on representational art and the importance of content and story in an age of abstraction and stylistic emphasis.

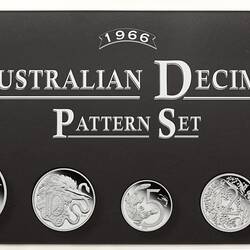

In 1967 the Australian Coin Review held a competition to design an unofficial Australian crown. Andor's design, which was based on his unsuccessful submission in the competition for the new Australian decimal currency, was the winner. It was subsequently issued and sold by the magazine, and the flying swan crown (or the Goose Dollar, as it was affectionately but incorrectly known) became a collector's piece.

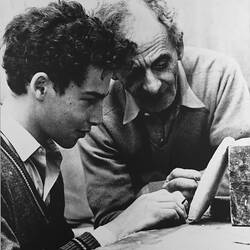

Andor designed, built and furnished with his own designs a home and studio in the Melbourne suburb of Kew. His younger son Michael, born in 1945, continues the Mészáros tradition of sculpture and medal-making from the same studio. Andor died in 1972; his biographer observed that his works displayed the qualities of 'courage, dogged endurance in the face of adversity, grief, the strength and persistence of love, a delight in sexuality and a marvelling at the wonders of the natural world.'

Andor's work is held in public collections in Budapest, Stockholm, Baghdad and Breslau, as well as state art galleries in South Australia, Western Australia and Victoria.

References

Semmens, Kelman 1972, Andor Meszaros, Hawthorn Press, Melbourne

Sharples, John 1990, Medals as Art: Australia and the Meszaros tradition, Museum of Victoria and the Royal Australian Mint, Melbourne & Canberra

Semmens, Kelman 2002, 'Mészáros, Andor (1900-1972)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, Canberra

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Localities

-

Authors

-

Article types