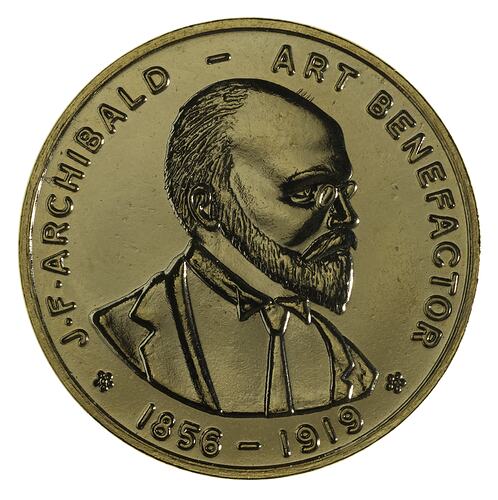

Jules Francois Archibald was born John Felton Archibald in Geelong in 1856. His mother died when he was four, and he was cared for by relatives while his father worked on the goldfields. He attended several local schools and developed literary ambition. At 14, he was apprenticed to printery Fairfax & Laurie, lesees of the Warrnambool Examiner, and stayed with the company when it founded the Examiner in 1872. He hoped to be a journalist, but was too shy to submit articles to his own paper. Instead, he sent articles to other papers.

At 18, Archibald left for Melbourne, and struggled in a range of menial positions including court and parliamentary roundsman before joining the Victorian Education Department as a clerk. During this time his fascination for French culture saw him change his name to Jules Francois. Archibald was dismissed from public service on 8 January 1878 ('Black Wednesday', when Premier Graham Berry dismissed public servants following the blocking of his Appropriations Bill), but he managed to find work as a clerk with a Queensland engineering firm. He was sent to work on the goldfields at Cooktown, experiencing a brief but important taste of rural life. He then moved to Sydney, and found employment as a clerk for the Evening News. He engineered his own elevation to the status of reporter.

Together with another journalist, John Haynes, Archibald then founded the Bulletin. The first issue was distributed on 31 January 1880, when Archibald was still only 24 years old. The issue sold out, and was soon known for its biting comments and insightful cartoons. It faced a libel suit and its principals were gaoled briefly, during which time William Henry Traill took over as proprietor and editor. Traill developed the Bulletin's nationalist and protectionist themes, causing Haynes to leave for a new career in politics. Archibald himself was suffering from bouts of depression and ill health, and in 1883 made his only trip to England. He sent home foreign dispatches and longed to become part of Fleet Street, but concurrently developed strong anti-British feelings and believed Australia should cut its ties to Britain. He fell in love with Rosa Frankenstein, and she followed him to Sydney on his return, and they began a disastrous marriage in 1885. Their only child died and she became an alcoholic. Archibald worried for her continually.

In 1886 Traill sold his interest in the Bulletin to enter politics, and Archibald ran the magazine as editor with a joint owner and business manager, William McLeod. Archibald continued to draw gifted writers and illustrators to the fold, including Henry Lawson. The Bulletin maintained its protectionist theme, as well as strongly supporting the White Australia Policy and was fiercely anti-Chinese. By 1889 the Bulletin was known as the 'bushman's Bible'; The Times commented that it had educated Bush Australia up to Federation. Its circulation reached 80,000 at a time when Australia's population was only 1,000,000. Archibald worked hard, but struggled with bouts of hypochondria, depression and anxiety. In 1902 he finally handed over the editorship, and decided to launch a monthly offshoot of the Bulletin, the Lone Hand. By 1906 he was quite mad, and ordered absurd quantities of wine for the launch of the magazine. With his wife Rosa's signature he was removed to Callan Park Asylum. He was discharged and re-admitted until 1910. During lucid periods he wrote poetry and occasional fiction. Some were published in the Lone Hand, which was finally issued in May 1907.

Archibald sold his interest in the Bulletin in 1914, with some bitterness at its conservativeness. He made his will, including money for a fountain in Sydney and support of distressed journalists. In 1919 he experienced a swan-song by working as an advisor for Smith's Weekly for several months, looking much older than his 63 years. He died on 10 September 1919.

References:

'Jules Francois Archibald' Australian Dictionary of Biography http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030046b.htm

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Localities

-

Authors

-

Article types