Hans William Henry Irvine, vigneron and politician (1856-1922) was born in Melbourne to John William Henry, an Irish flour-miller, and Mary Irvine, nee Gray [1]. Hans was allowed to shape his early business life as a foreman in his father's company at Learmonth, near Ballarat, and later became an apprentice lithographer at F.W Nivem and Co. of Ballarat, eventually becoming a partner in the business [2]. He married a coppersmith's daughter, Mary Jane Robinson, on 7 October 1885 in Ballarat East. On 9 May 1888, at 32 years of age and already wealthy after selling his share of the printing company, he purchased the Great Western Vineyard and cellars from Joseph Best for £12,000. At the time this included 55 acres of vineyards, between 60,000 and 70,000 gallons of cellar stock and 450 acres of grazing land [3]. Over the course of his tenure at the vineyard, he also purchased adjourning land to expand his business; this included the Arawatta (Indigenous Australian word for 'water hole'), Imperial and Saint George vineyards.

Irvine turned out to possess not only keen business sense, but also a desire to be a leader in the wine industry. In May 1891 he travelled to Europe to specifically investigate the process of Champagne making, with the intention of producing the wine at his vineyard [4]. He also employed the service of a French wine-maker, Charles Pierlot, originally of the reputable Champagne House of Pommery [5]. Pierlot was to prove invaluable in creating Irvine's sparkling wine, ensuring that the traditional méthode champenoise used to make French Champagne was employed at Great Western. The only unconventional aspect of Irvine's sparkling wine was that it was produced from a grape variety Irvine called 'white pinot', which in 1976 was revealed to be a Bordeaux variety called ondenc [6]. The traditional French champagne vines, pinot noir, developed leaf roll at Great Western and did not flourish. It was this same meticulous spirit that may have led Irvine to keep a small amount of American vines on his property, such as Riparia Grand Glabre and Riparia Martin, which were resistant to the deadly vine pest, Phyloxera. The aphid plague had spread through Europe in the late 19th century and the Rutherglen district in the 1890's and although it never reached Great Western, Irvine continued utilising the vines for their resistant nature [7].

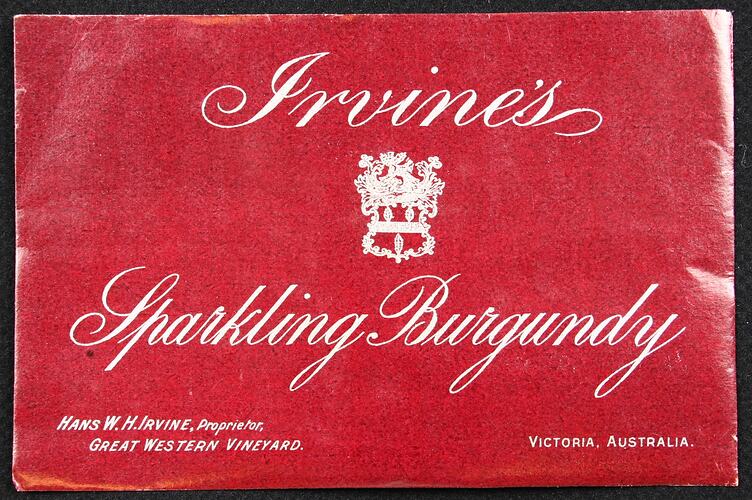

In 1894, Irvine began a process of extending the underground cellars that Joseph Best had already began to develop. By 1907 these 'drives' were over 1.6 kilometres in length [8]. In this vast area, free from large fluctuations in temperature, Irvine laid down 2000 bottles of sparkling wines, with great results. Described in a Great Western pamphlet as ".a happy blend of sweetness and light.", Irvine's Sparkling Wine was the first successful Champagne grown in the colonies [9]. The bottles, flavouring and machinery for the wine making process were specially imported from France, at great cost, as normal bottles and corking machines were unable to withstand the high pressures associated with producing sparkling wine. At the 1900 Paris Exhibition, Irvine's Sparkling Wine won the coveted gold medal [10].

Irvine was a meticulous businessman, keeping records of every national and international prize his wines claimed which included: a 1895 Bordeaux Exhibition Prize in France for his claret (NU 18541); a medal for his red wine in the Warrnambool Industrial & Art Exhibition in 1896 (NU 17890); and the 1902 Champion Prize of Australia medal from the Royal Agricultural Society of Victoria for his dry wine (NU 18543).

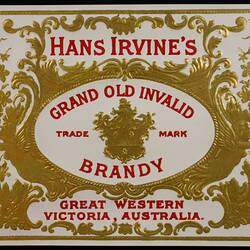

He also endeavoured to personally sample all his competitor's wines, and kept detailed notes on the taste and clarity of each example [11]. He became so wealthy by the early 1900's that he was able to purchase his competitor's wine for distillation into his Three-Star Brandy. He was also concerned with cleanliness and order, and gave very specific orders to his employees on how to keep their workspaces clean and hygienic. His influence as a businessman extended to the political sphere, and in 1903 he was elected as the member for the Grampians in the House of Representatives. In 1892, he was asked to produce a report on the Australian Wine Industry for the Minister of Agriculture, and he often wrote opinion pieces in local newspapers, mostly aimed at the Government's lack of support for the wine industry. He was also fond of entertaining and through this established invaluable political and social connections, such as his close friendship with Lord Hopetoun, Governor of Victoria and Australia's first Governor-General. He would often cement such friendships by naming one of the newly opened underground drives after his allies. The Dame Nellie Melba drive was opened in 1910 after she reportedly visited the winery and asked for a champagne bath, and Lord Hopetoun himself opened his own drive in 1903 [12].

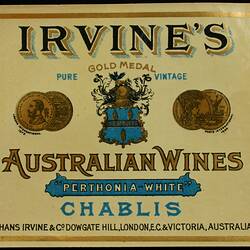

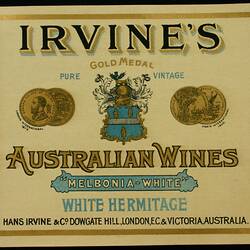

In 1905, Irvine purchased and opened a depot in Dowgate Hill, off Cannon Street, London, and appointed his nephew, Alfred Osler Watson, as manager [13]. At this time he already had two Melbourne depots, one located at Robb's Buildings, 527 Collins Street, under the direction of Mr. H. J. Guinn and one at Clarke's Buildings, 10 & 11 Bourke Street West, under Mr. J. H. Chambers [14]. Within months he was the largest exporter of Australian wines to Britain, and, according to an article in the British Australasian "...the first Australian wine grower [to] come to London to put the product of his own vineyard upon the wide market" [15]. On this trip he also travelled once again to France to bring back more experienced Champagne makers and increase his knowledge of the wine industry. Following on from his success, including winning over 1,000 gold medals at exhibitions, as well as his significant contribution to the Victorian wine industry, he and several other fellow winemakers formed the Viticultural Society of Victoria in 1905. Irvine was unanimously elected its first President on 3rd January 1906 [16].

In 1908, after five years of fruitless communication, Irvine gained permission from Sir William Carrington to use the Royal Seal on his wines. This included the use of the phrase ".by appointment to His Majesty the King and H.R.H Prince of Wales" [17]. Such an honour was in keeping with Irvine's focus on advertising and brand promotion. He made sure his Sparkling Wines held the monopoly for the launching of ships in the Melbourne area, and toyed with the idea of supplying wines to the Armed Forces during World War One [18]. He coordinated his labels and his signage to reflect the spirit of Australia (his most famous wines were named after Australian capital cities), as well as paying tribute to the mother country by utilising the strong red, blue and white of the English flag. He even utilised railway advertising, with most stations in London containing a colourful pressed metal plate with his brand name on it, and produced small promotional booklets that he included in every box of wine sold. He varied his advertising depending on the seasons, and at Christmas time he produced a special 'Christmas Edition' box of 14 wines [19]. In 1908, Irvine's wines won the Grand Prix at the Franco-British Exhibition, where they were coupled with an innovative stall that had four radiating arms [20].

Irvine considered selling the business as early as 1910, but it took the death of his wife, Mary, in 1915, the closure of his London depot in 1912 and the friendship of Mr. Benno Seppelt of South Australia, to convince him. In 1918, the Melbourne Cellars and the Great Western Vineyard passed to Seppelt and his sons for the sum of £100,000 [21]. Irvine subsequently purchased a grazing property, Kockatea, in Western Australia, some mining shares, and retired to Rockely Road, South Yarra. In 1922, he sought medical advice in London for a gastric ulcer, but died on 11 July following a routine operation [22]. His body was returned to Victoria in a lead coffin on board the steamer Raranga and buried, alongside his wife, in the Great Western Cemetery. His estate, valued at £173,356, was left mainly to friends and relatives, as he died without an heir [23].

References:

[1] David Dunstan (1983).'Irvine, Hans William Henry (1856 - 1922)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 9, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, pp 437-438.

[2] Ballarat Star, April 30th, 1888, The Australian Traveller, October 7th, 1905

[3] Ballarat Star, May 9th, 1888.

[4] L.R Francis (no date).100 Years of Wine Making: Great Western 1865-1965. Melbourne: Private publisher .

[5] Ararat Advertiser, April 30th 1891 and September 18th, 1906

[6] W.S Benwell (1960).Journey to Wine in Victoria, Melbourne: Pitman.

[7] The Argus, March 8th, 1906.

[8] John Beeston (1994).A Concise History of Australian Wines, Sydney: Allan & Unwin.

[9] 'Tarara', Hans Irvine's Great Western Vineyard, Victoria, Australia, London(?): Hans Irvine & Co., 1906.

[10] Ibid.

[11] State Library of Victoria, Irvine Manuscript Collection, box 1563/1

[12] Ibid, box 1563/2

[13] Ibid, box 3524/3

[14] Stawell Times, June 14th, 1889.

[15] British Australian, August 5th, 1905.

[16] State Library of Victoria, Irvine Manuscript Collection, box 3527/2

[17] Letter between Alfred Watson and the secretary of Sir William Carrington, September 7th, 1908.

[18] United Services Gazette, July 28th , 1910.

[19] Letter between Irvine and his nephew, Alfred Watson, November 11th, 1909.

[20] Stawell Times, July 21st, 1908.

[21] David Dunstan (1994). Better than Pommard! A History of Wine in Victoria. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publications.

[22] Ararat Advertiser, July 12th, 1922.

[23] State Library of Victoria, Irvine Manuscript Collection, box 3528/3

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Localities

-

Authors

-

Article types