Theodor George Henry Strehlow was born at the Hermannsburg Mission, Central Australia, in 1908. He grew up learning the Arrernte language spoken by the local Aboriginal population and was introduced to German literature, Greek, Roman by his parents. His father, the Pastor Carl Strehlow, wrote an important description of the Western Arrernte and Luritja Aboriginal people at Hermannsburg between 1907 and 1920 that in many ways foreshadowed the work of T.G.H.

In 1932 after graduating with an Honours Degree in English Literature and Linguistics from the Adelaide University, Strehlow returned to Central Australia to study the Arrernte languages. A quote from the biography by Ward McNally defines Strehlow's intention at this time: "The fact is that, although I speak the language, I scarcely know anything about the traditions of the people with whom I grew up, and whose respect and trust I need to be able to do what I might make my life's work. I want to learn all I can from the old men. They're the ones with secrets locked in their brains." (McNally, 1981, p.36)

In 1933, he was asked by some of the Arrernte elders from Alice Springs, who were concerned that their knowledge would die with them, to record their sacred rituals and songs. Strehlow was soon asked to photograph and film the ceremonies associated with these traditions. He soon began systematically recording the religious beliefs, ceremonial songs, social systems of Central Australian Aboriginal men as well as producing linguistic analyses of the Arrernte language.

During his work in Central Australia, Strehlow became aware of the great changes occurring in Arrernte society and of the mistreatment of Aboriginal people by some sections of Australian society. His concerns, and actions, primarily as the Patrol Officer for the Central Australia district (1936-42), earned Strehlow criticism and ridicule in some sections of society, but a great respect from the Aboriginal people of the area. After serving in the Australian Army during World War II, Strehlow was soon back in Central Australia as a university affiliated researcher, renewing his contacts with Aboriginal elders and building on the material that he had gathered during the 1930s.

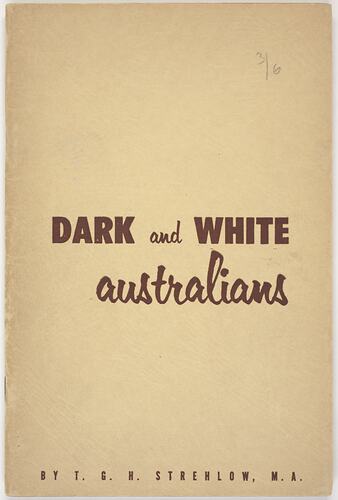

Between 1946 and 1974 Strehlow made numerous visits to the Central Australia, assisted by research grants from various organisations. He became an outspoken critic of mainstream society's treatment of Aboriginal people, maintaining that 'white Australians' could learn a lot from the moral, poetic and social lives of Aboriginal people.

Strehlow's four decades of work resulted in one of Australia's most comprehensively documented collections of Australian indigenous culture. He wrote over one hundred papers, articles, and books, and amassed a huge quantity of artifacts, myths, songs, photographs, films, sound recordings, field diaries and translations which are currently stored at the Strehlow Research Centre in Alice Springs. He died in 1978 aged seventy years.

References

McNally, W. (1981). Aborigines, artefacts, and anguish. Adelaide: Lutheran Publishing House.

Hill, B. (2003). Broken Song: T.G.H. Strehlow and Aboriginal Possession. Milsons Point: Random House.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types