Summary

Note: This object includes derogatory references to a particular cultural group. Such depictions are not condoned by Museums Victoria which considers them to be racist. Historical distance and context do not excuse or erase this fact.

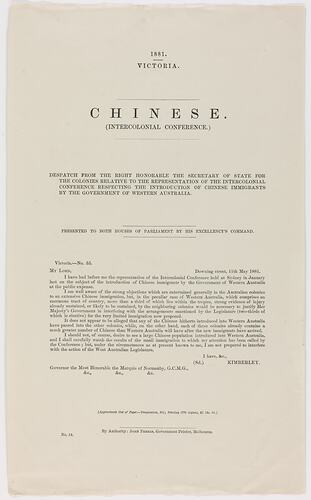

Document tabled in the Parliament of Victoria in 1881 entitled 'Chinese Intercolonial Conference'. It was printed in Melbourne by John Ferres at the Government Printing Office. The document is a despatch from the Colonial Secretary of State in London in response to concerns raised at an Intercolonial Conference in Sydney about the introduction of Chinese immigrants by the Western Australian Government. The Secretary states that there would need to be strong evidence of the negative impact, caused by Chinese immigration to Western Australia on the other colonies before the British Government could justify interference in Western Australian policy.

This document highlights the growing concern within the Australian colonies at the time about Chinese immigration. Anti-Chinese sentiment had been increasing in the Australian Colonies since the 1850s, when the discovery of gold in Victoria and New South Wales saw a substantial increase in Chinese immigration. Race related riots at Buckland River in Victoria in 1857 and Lambing Flat in NSW in 1860 were graphic illustrations of the extent of anti-Chinese feeling in the Australian Colonies. Despite this move by Western Australia to allow Chinese immigration, due to labour shortages, by 1888 all the Australian Colonies restricted Chinese Immigration which prepared the way for the Immigration Restriction Act and introduction of the White Australia policy when Australia Federated in 1901.

Physical Description

Foolscap size, double sided cream paper document, with type on one side.

Significance

This collection of documents provides an important addition to the Museum's collection of nineteenth century material relating to immigration to Victoria. The collection holds a number of government publications and reports relating to immigration policy and processing post 1950s but little from the early period of colonial immigration. These documents illustrate the range of issues facing colonial immigration administrators such as immigrant selection, temporary accommodation and funding assisted passages. The paper on Immigrant Homes provides a fascinating insight into what accommodation was provided for homeless migrants in the immediate gold rush period, including a reference to Caroline Chisholm's Family Colonization Loan Society and a hospital established at Canvas Town. Reports relating to immigrant selection demonstrate issues of lack of agricultural and domestic workers - a perennial concern of colonial, state and federal governments - and perceived skills gaps in specialized agricultural pursuits. The Despatch relating to Chinese immigration to Western Australia, while not specifically about Victoria, does highlight the colonial anxiety regarding Chinese immigrants which led to the virtual banning of immigration from China in 1888.

This collection also shows the range of colonial and British agencies involved in immigration/emigration policy and administration, such as Colonial Land and Emigration Office and the Immigrant Agent in London and the Dept of Trade and Customs. In the nineteenth century immigration policy was controlled primarily by the British Parliament. Legislation such as the Passengers Act of 1855 attempted to establish uniform controls for migration throughout the British Empire and to ensure the safe passage of migrants. From the 1840s until the 1870s the British Colonial Land and Emigration Commission oversaw migration policy for the Empire. Immigration offices and agents in Great Britain and other countries worked at a local level to process applications and arrange voyages. Immigrants filled in application forms and attended interviews and under the British Passengers' Act of 1855 they also had to submit to physical inspections.

Colonial parliaments had a Printing Committee which decided which Parliamentary business would be printed. It was the law that printed documents were to be available from the Government Printer to the public for cost price . Typically, in the 1860s there would be a print run of around 560 copies and these were distributed to Parliamentarians, their Secretaries, the heads of relevant Departments and some Public Libraries/Mechanics Institutes. The remainder were held by the Government Printer for Public sale with the price often printed on the document. By the 1900s most documents & reports had a print run of around 800. Prior to the 1890s, most papers were printed on high 'rag' content paper which has ensured that they have usually survived in very good condition.

More Information

-

Collecting Areas

-

Acquisition Information

Purchase

-

Printer

John Ferres, Government Printer, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 1881

-

Place & Date Used

-

Inscriptions

Text: 1881/VICTORIA/CHINESE/(INTERCOLONIAL CONFERENCE)/DESPATCH FROM THE RIGHT HONORABLE THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR/THE COLONIES RELATIVE TO THE REPRESENTATION OF THE INTERCOLONIAL/CONFERENCE RESPECTING THE INTRODUCTION OF CHINESE IMMIGRANTS/BY THE GOVERNMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA.

-

Classification

-

Category

-

Discipline

-

Type of item

-

Overall Dimensions

21.8 cm (Width), 34.3 cm (Height)

-

Keywords

Chinese Immigration, Conferences, Government Policies, Immigration Policies, Immigration Selection, White Australia Policy