Summary

Australia became a nation when the six self-governing colonies united in 1901. Before this, the colonies were politically separate, with their own laws and parliaments. During the long political process that led to Federation, a stronger sense of Australian nationalism developed. But as this narrative explains, not everyone celebrated Federation in 1901.

'Melbourne has been transformed into a huge madhouse and its citizens into a crowd of gibbering lunatics. Never in its whole history has such a wild wave of lunacy swept with such blizzard force through its streets, never has common sense been so prostituted, never has the shrine of lickspittledom been knelt at by such a mass of hypnotised devotees.' ('A Few Days in a Mad House' in Tocsin, 16 May 1901)

Our national celebrations reflect Australian society and identity. Those excluded or opposed to the festivities of 1901 represent the political and cultural diversity of Australia at the time of Federation. While thousands of Victorians turned out on the streets to celebrate the final step of the Federation process, it is important to recognise that not everyone was celebrating. Although Australia had politically united as a nation, there were still divisions and some Australians were denied a place in the celebrations of 1901.

Some Australians were excluded from the Federation celebrations of 1901, and others disagreed with the way Federation was being celebrated. Although Federation brought many Australians together, through the unification of the six separate colonies, it was also a time when many people felt divided or excluded and the identity of Australians was being debated widely.

Aboriginal people

Aboriginal people received little attention in the celebrations and press reports of May 1901. However, occasionally reports mention their exclusion from the Melbourne celebrations. For instance, the Warnambool Standard reported on 16 May 1901: 'A dozen aboriginals have tramped from Encounter Bay, South Australia, to witness the arrival of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York. They were detained by the police, and will be sent back to their homes for the present.'

On 18 May 1901 they reported another story of an attempt to participate in the celebrations: 'Billy Hewitt, one of the few remaining members of the Port Fairy tribe of aboriginals, was provided, by collection, with money enough to visit Melbourne during the past week's festivities, and has returned full of wonderment at the gorgeous sights he witnessed, but greatly disappointed because he didn't shake hands with 'the King.' He essayed an entrance to the gates of Government House, to secure a private audience with the Duke, but the sentries declined to allow Billy to enter the precincts of the Royal home. Equally futile were his efforts to reach the Duke whilst he was at Parliament House, the police there being just as discourteous to the dusky Australian prince as had the Government House sentries been. However, Billy consoles himself that he alone of the tribe went to Melbourne and 'saw the king'.

When Aboriginal people were included in the festivities and royal engagements, it was generally as Australian curiosities, for the Duke's interest. On a day's hunting near Geelong, a 'surprise' was arranged for the Duke: 'The fine herds of cattle grazing on Mr Pearson's lands were admired by the Duke, for whom a surprise had been prepared on the road to Kilmany. Two Australian Royalties, King Billy and King Bobby, with their suite of half a dozen coloured brethren, had come in from Ramayuck [sic] station to pay a kind of courtesy call on His Royal Highness, and had built their mia-mias on the side of the road....'

Republicans

In the later part of the nineteenth-century a strong republican movement had developed in Australia. During the celebrations republican newspapers railed against the sycophancy of the dignitaries, accusing them of coveting honours and awards.

The royal couple featured prominently in all the festivities of May 1901. There was a great surge of popular enthusiasm for royalty and the Empire. But most republicans felt that although Federation itself was of benefit, the celebrations were too coloured by royalty and the British Empire. The Bulletin pointed out that it would be a foreigner opening the first Federal Parliament on 9 May: 'One day this week George, Duke of Cornwall and York, and various other kinds of dignitary, enters Melbourne in a glittering vehicle, with many flags and much Jingo howling, and opens Parliament. He will do it by reading, or looking on while someone else reads, a speech which he didn't compose, about things he doesn't understand, and then he will go away again - once more among the yells and banners of a devoted people.'

The unemployed and the poor

There was also criticism of the amount of money spent on the celebrations and decorations. John Fleming, a Melbourne bootmaker and activist for the unemployed, organised a protest of unemployed people, at the procession of the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York on 6 May, the day they arrived. Fleming decided that the unemployed should be represented amongst the dignitaries at the official concert on the evening of the 9 May. The Tocsin reported: 'So he just strolled in, and after a friendly confab with one or two Labour members, who greatly enjoyed the idea, proceeded to luxuriate in the toffiest part of the whole assemblage. His presence was a grief of mind to Detective Macnamany, who assiduously tailed him for up to three hours and a half. At the end of that time Fleming got tired of the sport and considerately gave the officer an opportunity of showing him the door. The unemployed, however, had been officially represented, and 'tis a good omen.' Unemployed people also attempted to present an address to the Duke, which was sent back, unseen.

General dissatisfaction with the amount of money spent on the decorations led the women's column in the Tocsin to comment: How many poor children could be beautifully and comfortably clad with the red and blue velvet used on the arches? We women have heard nothing but expressions of dissatisfaction from workers of all classes at the reckless waste of public money in all these theatrical arches etc.

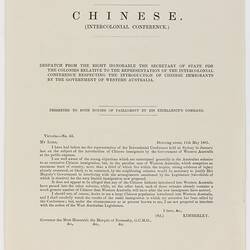

Chinese people

The Chinese community participated in the May celebrations in a spectacular way. However, anti-Chinese feeling was prevalent amongst many people, and they must have felt vulnerable in the newly federated nation, as one of the main policies of the new Commonwealth was a 'White Australia'. The Chinese communities spent £200 on the decorations and the arch in Swanston Street; they also presented addresses to the Duke of York, emphasising their loyalty to the King. In this way, they made sure they were visible in the 1901 celebrations, but the anti-Chinese climate of Federation Australia gave them no cause for celebration.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types