Summary

The Commonwealth of Australia was inaugurated on 1st January 1901 in Centennial Park, Sydney. In March, elections were held for the new Federal Parliament, and in May the celebrations focused on Melbourne, where the first Federal Parliament was opened in the (Royal) Exhibition Building. This narrative describes the temporary street decorations installed for the celebrations.

'The arches rose over the great masses of the people in the gorgeousness of their colours like so many rainbows set against a cloudless sky. The senses were whirled away with the bewildering spectacle, and for moments together buildings, people and arches alike were blended in a dizzy hundred-tinted wave of colour.' (The Age, 7 May 1901)

When Australia became a nation in 1901, the occasion prompted a flurry of arch building. In May, nine temporary ceremonial arches were built in Melbourne, two in St Kilda and four in Ballarat. Even small towns like Rokewood joined in with simple arches of greenery.

On 1 January 1901, the Commonwealth of Australia was inaugurated in Sydney. Arches decorated the streets. Victoria's contribution was an arch declaring 'Melbourne rejoices in the Commonwealth'. With Victoria's major figures away in Sydney, the celebrations back home were generally restrained. No inauguration arches were built in Melbourne. Some towns and suburbs organised their own events. Sale held a procession and erected a small arch.

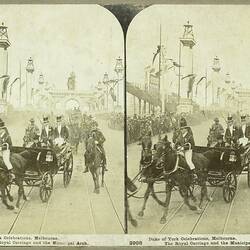

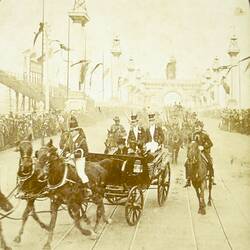

In May, Victoria became the centre of attention. The Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York visited to open the first Commonwealth Parliament in the (Royal) Exhibition Building. This combined honour ensured great revelry in Melbourne and throughout Victoria. Brightly painted banners, fluttering flags and sparkling lights decorated the streets and buildings. New plaster and paint finishes gave timber arches the solid appearance of marble and stone. The elaborate and vividly coloured arches were finished with rich fabrics, gold trim and patriotic decorations.

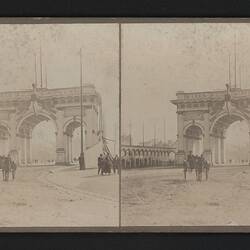

The Municipal Arch

For the May 1901 celebrations, the Prince's Bridge was transformed into an imposing gateway to Melbourne. The Municipal Arch was the centrepiece of the bridge decorations which also included Venetian flag poles and flaming towers. The Municipal Arch's design was described as "early Renaissance" or "Roman-Doric". Like the Commonwealth Arch in Sydney, it was similar to the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel (1808) in Paris and the Marble Arch (1828) in London. All drew inspiration from Roman structures such as the Arch of Septimius Severus (203 AD) in Libya, and the Arch of Constantine (316 AD) in Rome. Following the Roman tradition, the arch was inscribed with mottoes and poetry. It included the Latin motto from the British Coat of Arms and lines by the poets Virgil and Tennyson. Extending from the arch was the bow of the "Austral", a Roman-style ship. The six oars were inscribed with the names of the States. A lion's head symbolised imperialism.

The arch was intended to stand for 12 months. A protective galvanised iron roof, and new finishes such as rubberoid and waterproof paint were used. Sadly, only two weeks after the celebrations ended, the Argus commented: 'The once beautiful arch on the bridge is daily becoming less and less beautiful, and the 'ravages of time' are likely soon to convert it into a disfigurement of the chief entrance to the city.'

Monarchy and Empire

Although it was a new nation, Australia had a British head of state, sang 'God Save the King' as its anthem and flew the Union Jack. Unlike the Sydney arches in January, the Melbourne arches had a strongly royal theme. The Victorian Government built arches to honour the King, the Duke and the late Queen Victoria. These were covered in royal symbols, images, colours and patriotic mottoes. Loyalty to the monarch was also obvious in the other arches and decorations. Table Talk's female columnist freely admitted that the 'revelry and pageantry' of the Commonwealth celebrations was really in honour of the royal couple.

Radical newspapers like Tocsin and the Bulletin criticised the 'grovel' made to the 'Jookoyork'. The Bulletin's female reporter in Melbourne complained: 'There was too much Cornwall-and-York and too little Commonwealth on all the mottoes and designs'. The cost was also criticised, as in this poem from the Bulletin:

And who will pay the bill?...

For the fireworks, gorge, and swill,

For the arch on the street and hill?

Why - the common people will!

Arches for a City Beautiful

We see what wonders can be worked with arches, what pleasure they give to the eye, what charming interruption to the skyline. Why not...discuss the advisability of erecting a permanent arch or two in granite or marble to be a beauty and a joy forever? (Table Talk, 2 May 1901)

From the late 1880s to the early 1920s, Australia was influenced by the City Beautiful movement. The movement, from the United States, sought to create beautiful and harmonious civic designs. It promoted classic Renaissance principles including the use of arches. Ballarat's Avenue of Honour Arch is a rare example of a permanent arch.

In 1901 Davis Syme, owner of the Age, began a fund to build a memorial to the late Queen Victoria. A marble version of the Municipal Arch was suggested. Donations were slow, indicating a lack of public support, and no arch eventuated.

During the Centenary of Federation in 2001 the Tattersall's Federation Arch will stand on the Princes Bridge, in the same spot as the Municipal Arch in 1901. Then it will be shifted to another location in Melbourne for 10 years. It acknowledges the use of Federation arches a century ago and, with a modern twist, keeps the tradition alive.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types