Summary

Australia became a nation when the six self-governing colonies united in 1901. Before this, the colonies were politically separate, with their own laws and parliaments. During the long political process that led to Federation, a stronger sense of what it meant to be Australian was formed; and as this narrative shows, that meant being of British descent.

'[It is] of no use to shut our eyes to the fact that there is a great feeling all over Australia against the introduction of coloured persons. It goes without saying that we do not like to talk about it, but it is so.' (John Forrest, later the Commonwealth Minister of Defence, at the Federation Convention of 1898.)

At the time of Federation, most Australians feared that the introduction of people from non-European backgrounds would threaten the security and unity of the new nation. They believed that Australia should be a nation of people of British descent and that an increase of the population was necessary for Australia's survival. Over the first few years, the new nation primarily encouraged British immigration, but tolerated migrants from Northern Europe and to a lesser degree from Southern Europe. Few Europeans sought to migrate to Australia before World War One, but after the war, Southern Europeans as well as non-European migrants, were excluded from migrating to Australia.

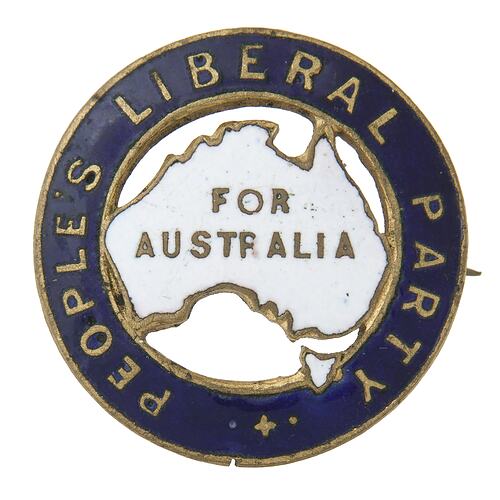

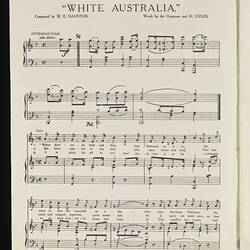

The majority of the leaders of the Federation movement felt that steps should be taken to produce a 'White Australia'. Federation would make this goal easier by making strict immigration restrictions more enforceable. This vision of the future Australia overlooked both Aboriginal people and people who had already come to Australia from non-European countries like China, the Pacific Islands, India and Japan.

Wages and racism

At the time of Federation, 'coloured people', women and young people, were paid less than white adult male employees. White male workers felt these groups were stealing jobs and there was particular hostility towards Chinese workers. Animosity was also directed at Pacific Islander labour in Queensland.

A major point of discussion was 'blackbirding', the practice whereby people from the Pacific Islands were kidnapped or fraudulently recruited by sailors and taken to the Queensland sugar farms where they worked in conditions that verged on slavery. Workers and unions were strongly opposed to this practice, as they felt it undermined wages and denied white men jobs. But others argued that the sugar industry was not viable without this cheap labour. The new Governor General, Lord Hopetoun, summarised the scale of costs to employers in a letter to the Prime Minister, Edmund Barton: 'A Kanaka [a person from the Pacific Islands] costs ½ crown [2 shillings 6 pence] a day including wages, food, clothing, cost of introduction from the islands and return journey thither. A Jap costs about 3s[shillings] a day on the same basis. A Chinaman about 4s 4d[pence]. An Indian about 5s. While I sympathise with the sentiment of the people which is, rightly I think, in favour of a White Australia, I don't want to see a great industry brought to a standstill and I know your feelings are the same as mine.' The average white male wage was about 7 shillings per day.

Much hostility was directed towards Chinese workers on the issue of wages, but it was rarely advocated that all people should receive equal wages. During preparations for the May 1901 Trade Union procession, the unions refused to allow the Chinese community to participate in the march. Instead, a separate Chinese march was held on 7 May 1901.

Restricting immigration

The six colonies had begun to restrict immigration to non-Europeans before Federation. However, central to the goals of Federationists was the further restriction of immigration, particularly from China. The Immigration Restriction Act was one of the first major acts to be passed by the new Parliament. This act abolished nearly all non-European immigration. Britain was opposed to any system of immigration restriction based solely on race. It wanted British subjects to be able to travel freely within the Empire, with no limitations based on colour. Because of this, Australia adopted the South African dictation test, given in any European language, to screen out virtually all non-white immigrants. Alfred Deakin explained in the Morning Post: 'Mr Chamberlain [the British Colonial Secretary] long ago laid down the principles that no discriminations could be authorised if they applied by name to particular peoples or complexions. It is for this reason that our Immigration Act sanctions in unlimited phrases the exclusion of all comers, although designed and used only to exclude the coloured races...In fact and in effect our colourless laws are administered so as to draw a deep colour line of demarcation between Caucasians and all other races. No white men are stopped at our ports for language or any other tests...On the other hand all coloured men are stopped unless they come merely as visitors.'

On arrival, immigrants had to pass a dictation test, by writing 50 words in a European language which the Immigration Officer would choose. At the same time, laws were passed to limit licences for Pacific Island labourers and, after 1906, to deport them. In 1903, the Naturalisation Act made non-Europeans ineligible for Australian citizenship. These restrictions on immigration became known as the White Australia Policy.

Aboriginal people in the new Commonwealth

There was very little discussion about Aboriginal people in the development of the constitution and Federation. Most Australians wrongly believed that Aboriginal people and their culture would die out in the near future. The new constitution stated that they were not to be included in the national census. Nor did the Commonwealth have the right to make laws regarding Aboriginal people; this remained a responsibility of the States. By 1912, all Aboriginal people of mixed descent were removed from Aboriginal reserves around Australia, with the goal of assimilation into the white community. The principle of assimilation also led to the removal of Aboriginal children from their families and cultures.

Aboriginal people were not given the right to vote in Federal elections, except in states that had granted Aboriginal people the vote prior to Federation. However, the legal interpretation of this clause was unclear. In 1902, the first Solicitor General interpreted it to mean that no new Aboriginal voters could be enrolled to vote in Commonwealth elections. Despite a successful challenge in 1924, and Aboriginal activism throughout the 1930s and 40s, it was not until 1962 that all Aboriginal people were given the Commonwealth vote, and not until 1965, that Aboriginal people could vote in all state elections.

The beginning of a new nation

Most of the people sitting in the Exhibition Building at the opening of the first Commonwealth Parliament believed in the creation of a 'White Australia'. One man who had fought against the Immigration Restriction Act is visible in the Tom Roberts painting of the event. Mr Eitake, the acting Japanese Consul General had lobbied the leaders against the Immigration Restriction Act for two years before Federation. By the end of 1901, his fight was unsuccessful; the White Australia Policy had begun to be implemented and would not begin to be dismantled until the 1950s. In 1966, all racially discriminatory migration selection was removed from Australia's migration policies and processes, and in 1973 the White Australia policy was completely revoked.

Since then, Australia has become a more racially tolerant society. Today, most Australians recognise the contribution greater cultural diversity has made to the community. Many are working towards a meaningful reconciliation with Aboriginal people and some official recognition has been given to their prior ownership of the land in the Mabo judgement of the High Court. The injustice and prejudice in Australia's history is now beginning to be acknowledged.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types