Summary

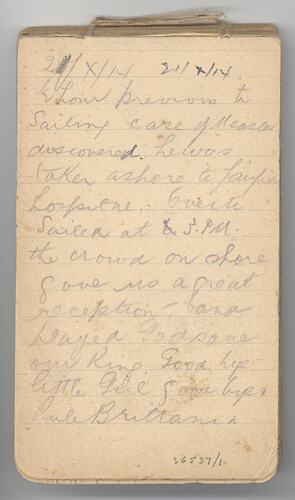

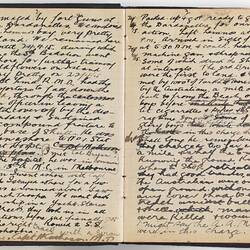

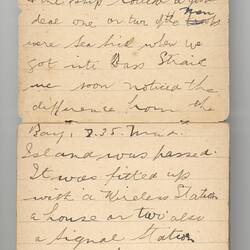

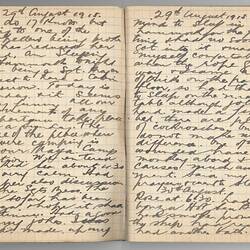

Diary consisting of three notebooks, one without cover, written by Corporal S.W. Siddeley between October 1914 and September 1915. His diary covers the first convoy, the landing of the Anzacs at Gallipoli and the campaign there. It diary contains graphic details of the landing at Gallipoli and the wounds of many, and his work in a field hospital on the peninsula.

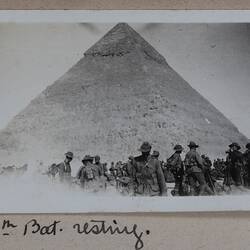

William McQueen Saxon ('S.W') Siddeley was a 19-year-old private secretary when he enlisted at Broadmeadows on 18 August 1914. Siddeley became a member of the Australian Army Medical Corps, First AIF, attached to the 5th Battalion, regimental number 1053. He embarked for service abroad on 21 October 1914, and took part in the first landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. His character and conduct while serving in the AIF was described as 'good'.

In May 1915, while still in Gallipoli, Siddeley reported to have 'defective eyesight', and his Casulty Form indicates that he left for Australia on the 'Euripides' on 29 August 1915, arriving 1 October. After time in hospital in Australia, and extended furlough, he was discharged from the AIF on 15 May 1916, being 'medically unfit' 'not due to misconduct'. On 1 November 1916, he was sufficiently recovered to begin duties as a Canteen Sergeant on the troopship HMT 'Afric'. He went overseas again, but only briefly: on 12 February 1917 the 'Afric' was torpedoed and sunk in the English Channel. Five died in the explosion and 17 drowned; 145 survived. This tragedy marked the end of Siddeley's war-time service: he left Plymoth for Australia on the 'Beltana' ('Services no longer required') on 17 March 1917, arriving in Australia in mid-May. After the War, Siddeley (ironically) became an eyesight specialist, working from the Finks Buildings, 6A Elizabeth Street, Melbourne. The effects of the war continued; the family reported that he had one short episode when he was admitted to the 'neurotic ward' at the Heidlelberg Repatriation Hospital. He died (or was noted deceased) on 24 April 1971.

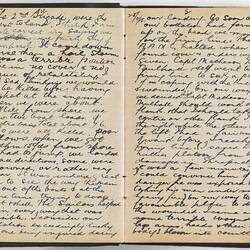

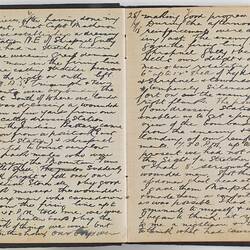

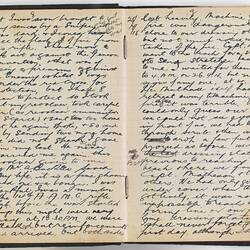

Extracts from the diary describing landings at Gallipoli are attached. Siddeley writes: 'Arrived in sight of land at 5.30 AM and could hear rifle machine gun and shrapnel fire some of which stuck to the ship at intervals. The third brigade were the first to land and were met by 1000's of Turks who were driven by the Australians a mile or more back from the beach. Our boys before landing lit cigarettes and rifles and some singing ragtime songs but several of the glory boys were killed...I think that I am quite correct in saying we all were fairly shy of shrapnel. It came down worse than a hailstorm. It was a terrible position to be in no cover and no chance of retaliating. I felt sad thinking we would all be killed before having a shot at the enemy. When we were about ½ a mile from shore, we saw two boat loads of Australians total about 76 who were all killed. Poor fellows when we got within 15 yards from shore we had to jump, we landed in all directions, some were drowned or rather very near.'.

Physical Description

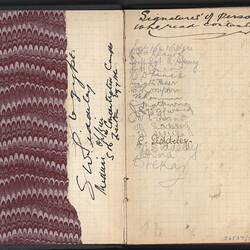

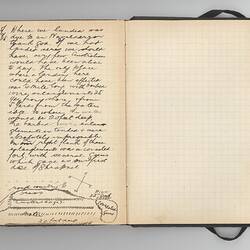

Three-volume diary, hand-written. The first volume (.1) is without cover, hinged at top, with stitch binding. Ruled with faint lines. Written in combination of pencil and pen. The second volume (.2) is bound in black leather, with elastic strap to secure closed (now very stretched and ineffectual). Printed with vertial and horizontal lines. Inside covers is decorative lining of purple pattern. Writing is principally in ink, with some pencil inscriptions. Includes sketches of battlefields. The third volume (.3) is bound in cardboard covered with black paper. Printed with vertial and horizontal lines. Writing is principally in ink. Includes a sketch of Shrapnel Gully.

Significance

Personal diaries provide a valuable insight into the daily life in the Australian armed forces. Some diarists record the mundane routines of daily life in military camps, or ports visited during voyages on transport ships; others provide graphic details of battles and medical treatments. Welcome letters and parcels from home are described, and friendships are recorded. Many soldiers complain about the food, or record welcome or festive meals such as Christmas. The diaries show many of the ways servicemen and women coped with the discipline, stress and tragedy of war.

More Information

-

Collection Names

Military Memorabilia Collection, Returned and Services League (RSL) Collection

-

Collecting Areas

Home & Community, Medicine & Health, Public Life & Institutions

-

Acquisition Information

Donation & Subsequent Transfer from Victorian Branch, Returned & Services League of Australia Limited (RSL), Mrs Ethel C. Siddeley, Oct 1984

-

Author

Corporal S. W. Siddeley - Australian Imperial Force (AIF), 1914-1915

-

Author

Corporal S. W. Siddeley - Australian Imperial Force (AIF), Gallipoli Peninsula, Dardanelles, Turkey, 1915

-

Inscriptions

[Extensive hand-written text]

-

Classification

-

Category

-

Discipline

-

Type of item

-

References

National Archives of Australia hold enlistment and other papers relating to Siddeley - Series number B2455, Barcode 8083551. Further information on Siddeley's diary is available on Museum Victoria's Imagining Australia 1914-1918 web site at [Link 1] National Archives of Australia also hold Department of Veterans' Affairs Repatriation Department Medical files and Hospital files on Siddeley, post-war, Series number B73/51, Barcode 12848064, and B73, 12848204.

-

Keywords

Psychiatric Patients, Wars & Conflicts, World War I, 1914-1918