The first 'national' Wattle Day was celebrated in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide on 1 September 1910.

The first known use of wattle as a meaningful emblem in the Australian colonies dates back to the early days of Tasmania (1838), when the wearing of silver wattle sprigs was encouraged on the occasion of an anniversary celebration of the 17th century European discovery of the island. The movement to link nature and nationalism began to grow in the late 19th century, with the approach of Federation. Publications such as The Bulletin also supported the rural ideal, in contrast to the moral degeneracy of the city.

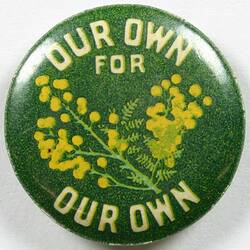

Of particular importance to the development of Wattle Day was the Australian Natives' Association (ANA), established in 1871. It was a strong advocate for native-born Australians and for Australian Federation. It later became an advocate for White Australia. The ANA was keen to find a national flower for Australia, like the thistle for the Scot and the shamrock for Ireland. It argued for the wattle, which was eventually chosen as the national floral emblem. The wattle could be worn by anyone, reminding people that Australia was an egalitarian, classless society. It was also a feminine symbol, presenting the new nation as a young woman.

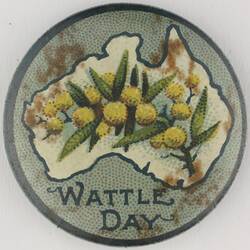

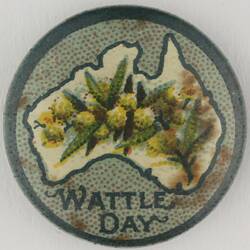

In 1889 the 'Wattle Blossom League' was formed Adelaide. In Victoria, spring excursions in search of wattle promoted Archibald James Campbell to establish the Wattle Club in 1899, and conduct annual expeditions on 1 September to collect wattle. Wider acceptance of a national Wattle Day was achieved at a major Australian Wattle Day League Conference in Melbourne in January 1913. Branches were formed in a number of States, with the general aim of officially proclaiming wattle as the national floral emblem and extending Wattle Day celebrations throughout the nation. About this time, wattle was officially introduced to representations of the Commonwealth coat-of-arms. And in December of the same year, the first wattle blossom stamp was issued.

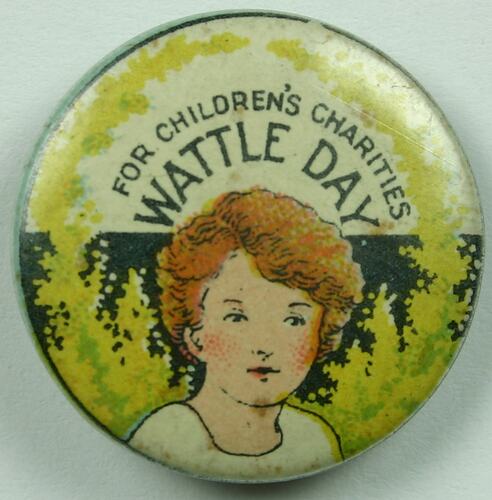

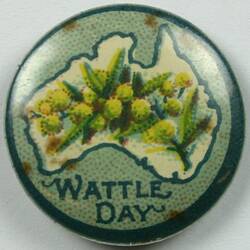

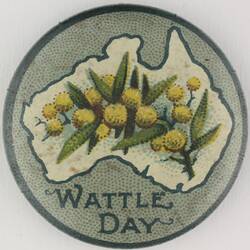

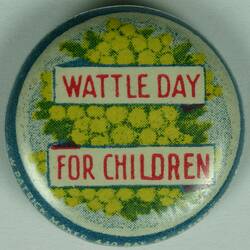

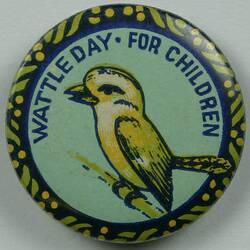

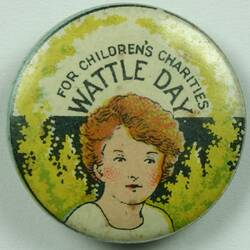

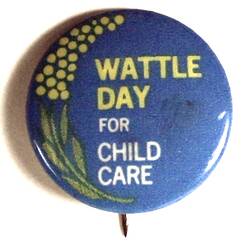

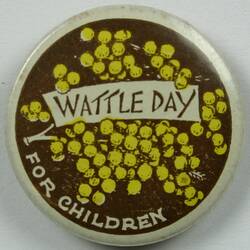

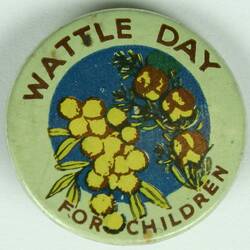

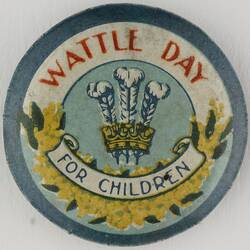

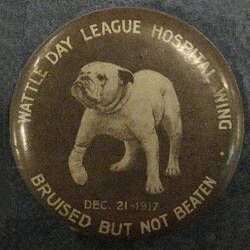

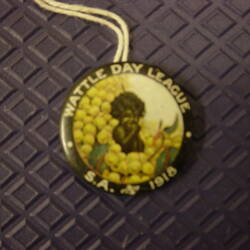

As public support for Wattle Day reached a peak, World War I broke out. Wattle took on a new significance in the war years as a potent symbol of home for military personnel serving overseas, and as a means of raising money for organisations such as the Red Cross. Beautifully designed Wattle Day badges as well as wattle sprigs were sold.

Ironically, the destruction of wattle for Wattle Day displays and fund-raising sales reached such heights that farmers within an hour of Melbourne locked their gates and wrote angry letters to newspapers. The use of badges depicting wattle instead of actual wattle saved many blooms.

The influence of Wattle Day waned as the 20th century progressed. Most states lost interest, but the Wattle Day League limped on in Victoria until the mid-1960s. The decline of Wattle Day appears to have had several causes. Foremost of these was the association of wattle with death. Children often died when it was blooming, of diseases such as diphtheria and whooping cough. Wattle also symbolized the Anzacs and the battlefields of the Somme. Further, the expression 'blood on the wattle' from Henry Lawson's poem evoked a class or cultural struggle that betrayed the idea of an egalitarian symbol. Although this declined during war-time, in the post-war period the bloodied wattle began to appear again as a symbol of heroism of a mythical White Australia.

In 1988 the idea of the wattle as a national flower was revived, and in 1992 the Governor-General declared 1 September as National Wattle Day.

References

Robin, Libby. 2002. Nationalising Nature: Wattle Days in Australia. Journal of Australian Studies. 73: 13-26 and 219-223.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types