Photographs in private albums form an important record of life at home and at the front during World War I, and of life in the years immediately after the war. By the early 20th century, many people owned inexpensive cameras that took small black and white photographs. Home photographic processing was also a growing hobby. Photographers on the home front recorded important events such as farewells, family parties and celebrations to welcome soldiers home.

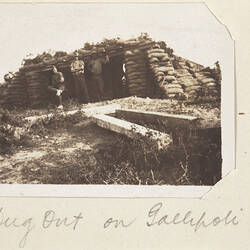

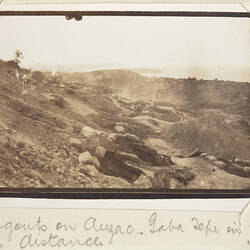

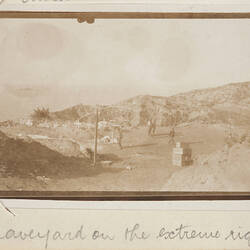

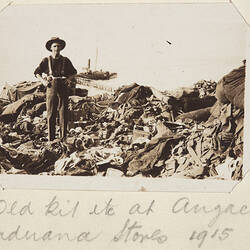

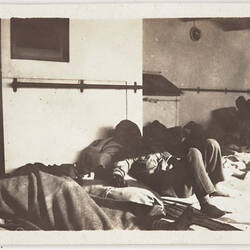

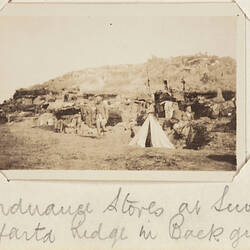

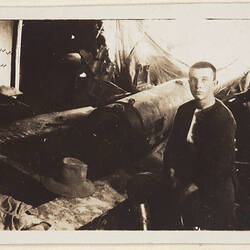

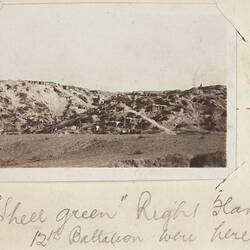

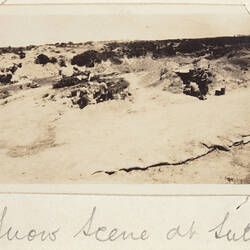

Some soldiers at the front surreptitiously took photos, against orders, to document their experiences in active combat zones, complementing their diary accounts; others were required to document the war by their units, which became part of the official war history. Charles Bean, Australia's official historian of World War I, unsuccessfully sought permission to take his own photographs. He was forced instead to rely on official British photographers until 1917. Soldiers' personal photographs include images from training camps, the war front, special meals such as Christmas dinner, local sights and citizens, and incidents that amused them.

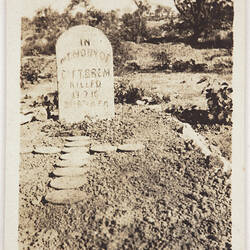

Melburnians were quick to show their loyalty when war broke out in August 1914. By the end of the war, two out of every five men aged 18 to 44 had voluntarily enlisted to serve, to fight distant battles in Europe and the Middle East. Many Melbourne men were in the 2nd Brigade, which took part in the Anzac landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. Within a fortnight one-third was dead or wounded. A year later the reinforced brigade was fighting in the front-line trenches at Pozieres in France.

Women played a vital role too, nursing the sick and wounded, raising funds to buy ambulances and guns, and organising food, clothing and newspapers for soldiers at the front. Across Australia, more than 400,000 men volunteered to fight. Of those, within five years more than 60,000 were killed and 156,000 wounded, gassed or taken prisoner. In total, two-thirds of the men who went overseas were killed or wounded, leaving scarcely a family untouched by the war.

Many men returned damaged, shell-shocked, bitter and broken. Returning from the battlefields with the soldiers was a devastating influenza pandemic. In two years, more people around the world died of flu than had been killed in the war. Yet the cost paid for the war seemed to confirm Australia's status on the world stage, and a growing sense of national identity was reinforced through the story of the Anzacs.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types