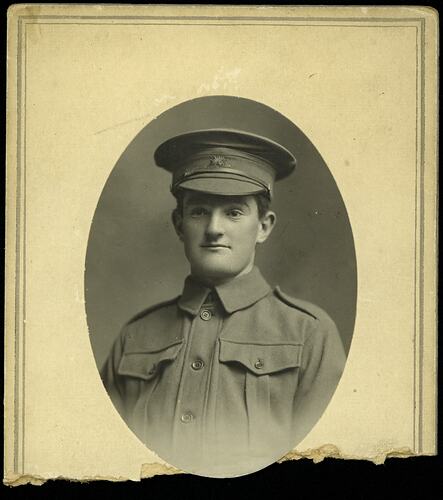

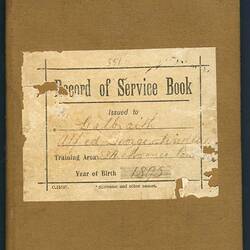

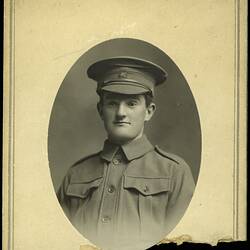

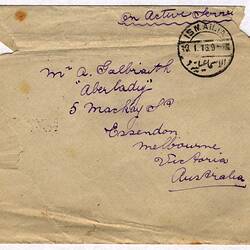

Born in Maryborough in 1895, Sapper Alfred George Finlay (aka Finley) Galbraith was the son of Amy (nee Greenwood) and Alfred Galbraith, General Secretary of the Victorian Railways Institute, Flinders Street, Station Buildings, Melbourne. Alfred began his military service as a Senior Cadet in January 1911 at the age of 16, when he was not yet fully grown - he was just over 5' tall and six stone in weight. (Two years later he was 5'9" and almost nine stone.) He served for 12 months as a signal engineer and 18 months in the infantry. These roles took him a little over two weeks each year, undertaken while training to be an 'electric fitter' then working as an electrician. He was living at 5 McKay Street, Essendon, when he enlisted in the AIF at Broadmeadows the age of 20 years and two months, on 15 July 1915 - service #3648. Australians had been fighting at Gallipoli for four months.

Alfred was initially rejected by the AIF: to enlist in 1914 a man had to be 19-38 years old, at least 36" chest size and at least 5'6" tall, and without physical issues such as unfilled teeth, flat feet or corns. The standards were so high that the '1914 men' still stood out in 1918. Selection requirements became less rigorous after the Gallipoli landing - for example, the height requirements were lowered to 5'2". Alfred's second attempt to enlist, in July 1915, was successful. He was one of many: enlistments in Victoria increased from 1,735 in May to 21,698 in July. (Gammage, The Broken Years, pp.9 & 14)

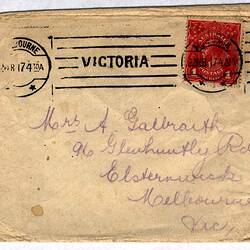

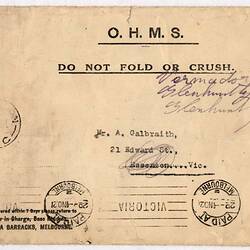

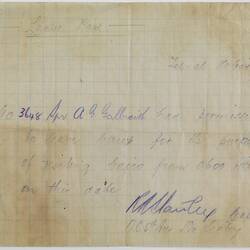

Alfred's father gave written permission for him to join 'the Military Forces to serve the Empire abroad' (his mother had passed away, as Alfred wrote on page 60 of his service record; when Alfred addresses a letter to his family he includes 'mother' - ST 041203 and 031215 - he is probably addressing his stepmother). The army utilised his existing skills and, after signals training at Broadmeadows (14/09/1915), he was made a sapper in the Signal Engineers (October 1915). Sappers were responsible for tasks including running out cable in shallow trenches for wire and radio communications. Alfred was placed in the 2nd Division Signals Company, Australian Engineers. He embarked from Melbourne on 23 November 1915 on the Ceramic, bound for Egypt. As he was leaving he thought of his little brother, and said to his family 'Don't let the little bloke forget me'. His family never forgot those words.

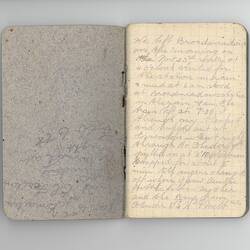

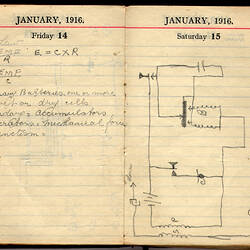

Alfred arrived in time for Christmas and wrote home to his family about the delicacies purchased for a celebratory dinner and life at Ismailia training camp. Alfred had a strong connection with his family and sent letters and messages home regularly. In early 1916 a new division of the Australian Army was created from available troops in Egypt. Alfred joined the 5th Division Signal Company (09/03/1916). The new division trained at Tel-el-Kibir and held a section of the Suez Canal defences.

In June 1916, the 5th Division sailed to Marseilles - Alfred was aboard the Canada - and travelled by train north to Hazebrouck, France. The men were billeted and trained 40 kilometres from the front line in French Flanders. They lived in barns and outbuildings that ranged from clean, dry and warm to very uncomfortable. Training included musketry, bayonet fighting, fitness drills and the use of gas masks, in preparation for the trench warfare of the Western Front.

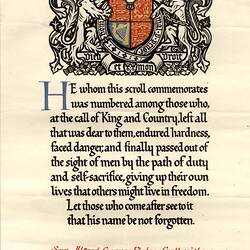

On 9 July the Signals Unit moved to the vicinity of Croix du Bac. On 12 July they moved again, to 'Sailly' (presumably Sailly-sur-la-Lys). On 15 July 1916, the 5th Division took over a section of the front known as the 'nursery', favoured as a place to introduce and initiate troops to the trenches. At 8pm, on his first day at the front, Alfred received a wound in the thigh and a 'penetrating wound in the neck' from an exploding shell whilst moving from one dugout to another. His death was noted the same day at the 8th Australian Field Ambulance. It had been less than a month since he had arrived in France and a year to the day since he had enlisted. Alfred and a man near him were probably the first soldiers of the 5th Division to be killed on the Western Front.

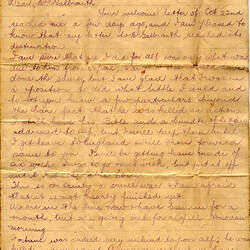

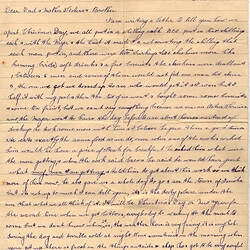

The unit diary for the 5th Division Signals records: '2845 Sap Johnston T. [Thomas] A. and 3468 Sap Galbraith A.G.F. Killed in Action 8pm. Both men were proceeding on line duty at Fleurbaix.' A fellow soldier described his death in more detail: 'The fatality occurred last night about eight o'clock, as he and three others were moving from one dugout to another; one shell passed over their heads and they took no notice, but the next minute a bigger one exploded right beside them; two escaped injury, one named Johnson was killed outright, and poor old Alf lived but a few minutes.' 'Did' writes that he was told this account by an eyewitness, and stresses that Alfred 'died as a soldier and a hero and I am sure that you are more proud of him now, than if he had stayed a slacker at home.'

If Alfred had not died on 15 July he would have faced significant danger. On 19-20 July the inexperienced 5th Division was involved in the Battle at Fromelles, with appalling losses, suffering 5,533 casualties in 24 hours, and many more men taken prisoner.

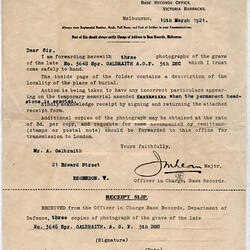

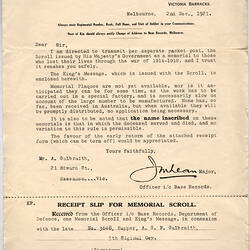

Alfred was buried in the Sailly-sur-la-Lys Canadian Cemetery, France, by Reverend W. Meredith Holiday. His two diaries were amongst his belongings that were sent to his father. His other belongings were listed as: a New Testament, two wallets, letters, cards, photographs, a pipe in a case, a cigarette holder pouch, a tie clip, a hone, a steel mirror and six coins.

Alfred was posthumously awarded the 1914-15 Star, the British War Medal and the Victory Medal.

Several family members have donated items in memory of Alfred. In 1985 a Mrs M. Jamieson donated photographs, correspondence and memorabilia. She is probably Marjorie Evelyn Jamieson, nee Galbraith, half sister to Alfred Galbraith. In 2011 his niece Jillian Galbraith donated digital copies of photographs relating to Alfred and lent material for display at Melbourne Museum. In 2021 further material was offerd to the museum, contributing to a significant legacy for Alfred Galbraith.

References

War service records, National Archives of Australia.

Jillian Galbraith, personal communication with Deborah Tout-Smith, March 2011.

Museums Victoria Alfred Galbraith collection.

Bill Gammage, The Broken Years, 2010 edition.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types