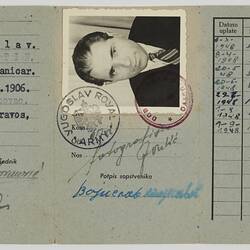

Mr Vojislav Stojkovic was born on 14 September 1906 in the former Republic of Yugoslavia. He married his first wife when he was 19 or 20 years old and had three children to with her - Petar, Radmila and Vida. His father made him join the army when he was in his twenties as a military policeman, as he did not like farm work, so that he could contribute cash to the family.

He was captured by German forces in 1942 and sent to work on a farm in Germany. It was here he first met Dimka (Dimitrinka Nikolova Caraschobanova).

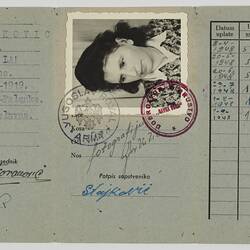

Dimka was born on 9 March 1919 in Bulgaria. In 1942 she was visiting family when the Partisans blew up a train, and as part of the retaliation, the Germans executed a number of young men and shipped a number of young women to Germany as slave labourers, including Dimka.

The labour camps where Vojislav and Dimka were held were located close to each other, and Dimka recalls she first saw Vojislav 'through a fence'. After that they saw each other only in passing from time to time and would talk whenever they got the chance. They met again in Russia when Dimka and a number of other Bulgarian women snuck away from the camp they were being held in and hid in the Yugoslav men's camp, which was where Vojislav was being held.

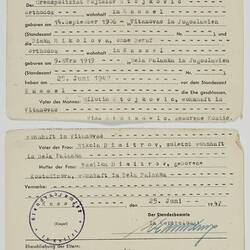

After the war, Vojislav and Dimka were placed as a couple in the same refugee camp in Kassel, West Germany. They got to know each better during this time and married there in 1947. During this time the couple traded items given to them by the Red Cross, especially coffee or chocolate, with the local German farmers for meat, eggs, cheese, chickens and pigs, etc. They also ran a still and produced a clear spirit from potatoes and other vegetables obtained from the farmers which they sold to a German pharmacist. He added colour and flavour and sold it on to the American soldiers as cognac.

One day both Vojislav and Dimka had to work and they entrusted the minding of the still to a friend. Even though they warned him not to drink the first spirit coming through the still he thought that they were just being stingy. The first liquid produced by the distillation process is highly toxic. The friend had a drink, passed out and without supervision the still caught fire. Vojislav, who was the camp fireman, was called to extinguish a fire at this own home.

In order to survive everyone had participated in the black market. Sometimes people would venture out into the countryside and steal from the German farmers that they had previously laboured for and the farmers would lodge complaints with the allied authorities. On one occasion a cow had been stolen from a farm. The Americans said 'we know it's here' and the residents said 'look anywhere you like'. Apparently as one building was searched, the cow was led through another until the whole camp had been searched. However over the next few days' sausages appeared for sale on the black market.

Personal presentation was very important to these ex prisoners, and the women in the camp would often take apart old clothes of good quality donated to them through the Red Cross, wash and iron the pieces and take them to tailors to be remade into new clothing. Anything that could be used to make clothes such as old parachutes and military tents was made use of. V

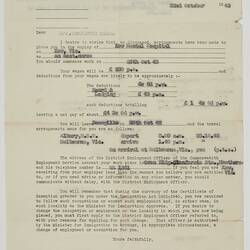

Vojislav and Dimka decided to emigrate and were given the choice of migrating to America, which was too hard to get into, Canada, which was too cold, and Australia, where they migrated. They came out to Australia via Naples on The Protea in 1948. Dimka recalls that despite everything she had seen and experienced during and after the war she had never seen such poverty or desperation as she saw in Naples.

It was the first voyage of displaced persons to carry both single and married people. Most passengers had no idea where Australia was and over the period of the journey many people started to worry about their future. Dimka recalls hearing stories that there were only black people in Australia and that a couple of people suicided during the voyage. She also remembers many people marrying during the journey, which took nearly three months, as the ship broke down for a long period of time somewhere in the Middle East.

On arrival to Melbourne they were immediately transferred to Bonegilla Migrant Camp. They weren't there for long, as after a few weeks Vojislav and Dimka found work through the Commonwealth Employment Service, and were given a small amount of money and a train ticket to Melbourne. On their arrival, Vojislav first worked in a brickworks factory in Brunswick and lived in Watsonia Barracks and Dimka worked as a live in psychiatric nurse's aid at Kew Mental Hospital.

Soon after this they moved into a rooming house in Brunswick close to Melbourne Zoo where they could hear the lions roaring at night. Dimka recalls this as a very happy time as the room was too small to spend much time in and so they went out a lot to the cinema and visiting other friends who had settled in Melbourne.

Australian people at this time were suspicious of foreigners and would often say things like 'come back when you can speak English' in shops when Dimka and Vojislav were trying to make themselves understood. Also at this time the range of foods available in Australia was limited to those familiar to Anglo-Celtic people and so the new European arrivals would track down producers of European foods. People would travel across Melbourne when they heard of a European deli opening or an Italian butcher or a Polish baker. People also often made their own smallgoods at home by purchasing a pig and butchering it themselves.

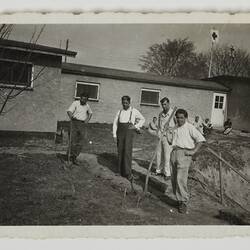

Between 1951-1954 Vojislav and Dimka lived in an old shop in Brighton with three other couples who they knew from the camps in Germany. In 1952 their daughter Nada was born, the only child in a house with eight adults. The couples often socialised, playing cards and having parties. Vojislav then found work at the Australian National Forge in West Footscray where he was employed until he retired.

They had been saving money for a deposit on a house and because of Vojislav's work and the fact that they never had a car; bought a house in Whitehall Street in Footscray. Dimka worked at the Bradmill Cotton Mill for many years, and then during her forties worked in the Melbourne Myer's cafeteria.

To pay off their mortgage as quickly as possible, Vojislav and Dimka rented rooms out to other recently arrived families, housing up to 16 people at any one time in what was luckily a large house. Usually a family of up to four would share a room, and have a kitchen and bathroom/laundry to share with other borders. These borders were often Yugoslav, Polish or German.

Their second daughter, Lily, was born in 1956 and for a number of years the Stojkovic family all slept in one room but had they own private kitchen and bathroom/laundry separate from the boarders. Nada and Lily remember this as a fun arrangement but it must have been very trying for Dimka and Vojislav. In a way the family acted as an informal migrant resource centre, helping recently arrived migrants settle in - Vojislav would help find the husband a job and Dimka would help the wife find work, either at the factories where they worked or through their friends and their contacts. Nada would often help their children settle into the local primary school.

In working class suburbs in Melbourne in the 1950s and 1960s it was not unusual for families to take in boarders for extra income and many of these boarders became lifelong friends of Dimka and Vojislav. By the early 1960s after the mortgage was paid off, they lived with one other Macedonian or Croatian family and by the late 1960s this era of taking in boarders was over.

Childcare was not readily available during these times and most people had to make whatever arrangements they could, preferably with family members. As Dimka and Vojislav had no family in Australia they would sometime offer free rent to boarders in exchange for child minding or find a local woman who wanted some work. Often these arrangements were very unsatisfactory but as Dimka needed to work and bring in an income she had to accept times when it was obvious that the children had been neglected. Dimka returned to work when Nada was 6 months old and when Lily was just 6 weeks old.

Vojislav and Dimka spoke limited English, but spoke Serbian, Russian, Polish and German. No one in the house spoke English, so Nada grew up speaking Serbian, German and Polish as a child, learning English only when she went to school, and Lily grew speaking both Serbian and English.

Vojislav died in Melbourne in 1987. A year or so after his death Dimka joined the Footscray Senior Citizens' Club and enjoyed many of their social events and trips. Initially she was treated with suspicion, as she was when she arrived in Australia, although when she was asked her nationality, she said she was Australian. Dimka died in Melbourne in 1998. Vojislav's and Dimka's two children continue to live in Melbourne.

More Information

-

Keywords

World War II, 1939-1945, Displaced Persons, Bulgarian Immigration, Immigration, Bulgarian Communities, Displaced Persons Camps, Immigration Policies, Immigration Selection, Immigrant Voyages, Migration & Settlement, Migrant Reception Centres, Yugoslavian Immigration, Yugoslavian Communities, Immigrant Shipping

-

Authors

-

Article types