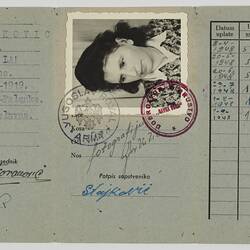

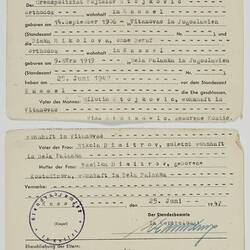

Mrs Dimka Stojkovic (nee Dimitrinka Nikolova Caraschobanova) was born on 9 March 1919, most probably born in Svilengrad, Haskovo Province, Bulgaria. She was the fourth of six children whose father died just six months after the youngest was born. Her mother supported the family by running a scrap metal business and the children were raised by their grandmother. There was one son and five daughters. The family sent the son through college but Dimka only went to school for two years of primary school, making her illiterate.

In her teens she worked for various families as a nanny and ended up living in the capital Sofia. She related to her daughter, Nada, that she went to the theatre, to a boxing match, restaurants and clubs with friends, some of who were Jews and Gypsies. Her younger sister Slavka was also employed as a nanny to look after the child of a wealthy family whose mother had died. When Communists invaded Bulgaria, her sister was arrested for crimes against Communism, due to her connection to wealth through this position, and was sent to prison. After her release, she married the child's father and they went on to have children of their own.

In 1942 Dimka was visiting family (possibly in Svilengrad) when the Partisans blew up a train, and as part of the retaliation, the Germans executed a number of young men and shipped a number of young women to Germany as slave labourers, this included Dimka. She was taken by cattle car for three months, being shunted aside for troop trains and sometimes spent weeks going nowhere. Just after their arrest, a number of the women including Dimka escaped from the train and met up with a band of partisans. Rather than helping them get away, the partisans robbed them of any jewellery they had and left them there for the Germans to recapture. Dimka had her earrings ripped out of her ears and refused to wear earrings until not long before her death in 1998.

Dimka ended up in Essen, Germany and worked in a factory making Meserschmidt engines. By the end of the war she was so ill from malnutrition and overwork that she ended up in the same hospital as the Jews who had been released from Bukenwald Concentration Camp. Many of the people from the local town also worked in the same factory and some were friendly towards slave labourers. By this stage many Germans were well and truly sick of the war. Many of the workers from the town were widows whose husbands and sons had died in the fighting. Camp guards generally disabled or amputee German soldiers returned from the Russian front who treated them ok or Czech guards/collaborators who often didn't.

During the war, the factory was bombed by allied forces. One day while being walked back to their camp after work, the women were strafed by two American fighter planes from a low height even though it was obvious that they were not soldiers. Dimka and the other women threw themselves off the road and into a ditch which was full of raw sewage.

One funny story that Dimka related to Nada about the camp was that young boys from the local Hitler Jungend would come up on weekends to spit at and insult the prisoners. The Gypsy women in the camp dealt with this by going up to the fence and exposing themselves to the children who would run off in horror.

Sometime after the forced labour camp was liberated a number of the women ex prisoners who included a number of partisan fighters (who were very tough and battle hardened) captured the most hated Czech guard, tied him up and tortured and mutilated him. Dimka and her friends were invited to come and see what was happening along with the other women and participate if they wanted to. When they saw what was happening they were horrified and with a number of others informed the occupation authorities although it was obvious that the man was going to die from his injuries.

Dimka she first saw her husband Vojislav 'through a fence', when he was being held in a labour camp close to hers.

Dimka was very keen to return to her family in Bulgaria, which was at the time under Russian control. She and a number of other Bulgarian women were relocated to a Russian camp prior to their return but felt very nervous and uncomfortable there. Dimka related to Nada that the Russians said that 'we are all comrades and equal, what's mine is yours and what's yours is mine. I have nothing, so I will take what is yours'. After a few days a group of Bulgarian women snuck away from the Russian camp and hid in the Yugoslav men's camp. Some of the Russian guards went there and demanded their return, threatening the Yugoslavs who stood their ground. After three weeks the Russian guards gave up. This is how Dimka found herself meeting Vojislav again.

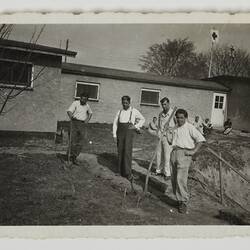

After the war, Vojislav and Dimka were placed as a couple in the same refugee camp in Kassel, West Germany. They got to know each better during this time and married there in 1947. During this time the couple traded items given to them by the Red Cross, especially coffee or chocolate, with the local German farmers for meat, eggs, cheese, chickens and pigs, etc. They also ran a still and produced a clear spirit from potatoes and other vegetables obtained from the farmers which they sold to a German pharmacist. He added colour and flavour and sold it on to the American soldiers as cognac.

Dimka was re-connected with her family in Bulgaria with the aid of the Red Cross. Although she didn't get to see her family again until 1972 when she returned to Bulgaria with her daughters Nada and Lily and by that time her mother and one of her sisters had died.

Dimka's younger sister Slavka also had two daughters, Julietta and Antonetta, who both became ballerinas. When the older daughter was studying ballet in Sofia in the mid 1960s she was bullied and harassed by the other students as the daughter of capitalists and attempted suicide. Her mother contacted Dimka and arrangements were made for her to go to Belgrade and live with Vojislav's oldest daughter Radmila and complete her studies in Yugoslavia. Julietta lived with them for two years, stayed in Belgrade, later married a Yugoslav man and today still lives in Serbia.

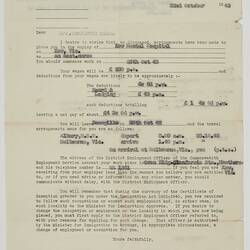

Dimka and Vojislav migrated to Australia via Naples on The Protea in 1948. On arrival to Melbourne they were immediately transferred to Bonegilla Migrant Camp. After a few weeks Vojislav and Dimka found work through the Commonwealth Employment Service, and were given a small amount of money and a train ticket to Melbourne. On their arrival, Vojislav first worked in a brickworks factory in Brunswick and lived in Watsonia Barracks and Dimka worked as a live in psychiatric nurse's aid at Kew Mental Hospital. Nada relates how her mother worked with seriously ill and often violent mental patients even though she had no experience, training or English language skills to do so. This rather insensitive arrangement lasted for around 18 months. At this time mental patients were often treated badly by the asylum staff, however Dimka realised that the patients would do anything for cigarettes, so she would bribe them with these to be docile and compliant. This didn't always work out as planned and she was attacked on a couple of occasions.

Soon after this Vojislav and Dimka moved into a rooming house in Brunswick close to Melbourne Zoo where they could hear the lions roaring at night. Between 1951-1954 Vojislav and Dimka lived in an old shop in Brighton with three other couples who they knew from the camps in Germany, and in 1952 their daughter Nada was born.

They had been saving money for a deposit on a house and bought a house in Whitehall Street in Footscray, with Dimka working at the Bradmill Cotton Mill for many years, and then during her forties worked in the Melbourne Myer's cafeteria. To pay off their mortgage as quickly as possible, Vojislav and Dimka rented rooms out to other recently arrived families, housing up to 16 people at any one time in what was luckily a large house. In 1956 their second daughter, Lily, was born.

Dimka visited her family in Bulgaria and her husband's family in Yugoslavia - in 1972 with Nada and Lily and then in the 1980s on her own. While Vojislav also visited his family they never travelled together as he wanted to go in the winter time when things were quiet in the countryside and only wanted to visit his family, while Dimka wanted to travel and see other countries as well. Both Nada and Lily also visited their families overseas a number of times.

Vojislav died in Melbourne in 1987. A year or so after his death Dimka joined the Footscray Senior Citizens' Club and enjoyed many of their social events and trips. Initially she was treated with suspicion, as she had been when she first arrived in Australia. When asked her nationality, she said she was Australian. After all she had lived in Bulgaria for 22 years, in Germany for six and the rest of her life in Australia. Although when questioned about what she did in the war, she replied that she 'worked for Hitler!' Dimka died in Melbourne in 1998.