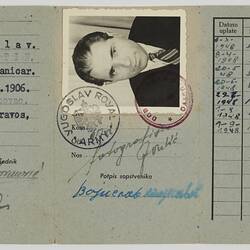

Vojislav Stojkovic was born on 14 September 1906 in Vitanovac village, in the former Republic of Yugoslavia, now Serbia. He came from a line of subsistence farmers of cash crops and sheep farming (wool and feta cheese). Vitanovac is now much smaller, with many houses empty and decaying, and the majority of its population elderly.

Vojislav married his first wife when he was 19 or 20 years old and had three children to with her - Petar, Radmila and Vida. They lived together in Vojislav's father's house. Vojislav's daughter (from his second marriage), Nada, relates that her father was known to be lazy and not very good at farm work. His father made him join the army when he was in his twenties as a military policeman, so that he could contribute cash to the family, which he did for around 12 years.

When WWII broke out, Yugoslavia was not a Red Cross signatory, and therefore Yugoslav soldiers weren't covered by the usual rules of war. In 1942 Vojislav was posted near Trieste when he was captured by the German forces. He was sent to work on a farm in Germany, which he hated, rather than being held elsewhere as a POW. To get off the farms he would deliberately cut his feet and infect them with manure so that he would be sent to 'hospital'. He was eventually warned not to do this again or he would be sent to a concentration camp. However, he was lucky when the commandant's cook died and he was given the job as he could butcher livestock and cook reasonable meals, thanks to his farming background.

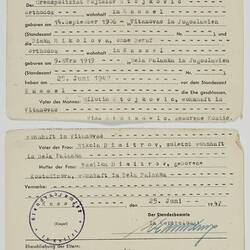

Vojislav met his next wife Dimka when she was working in a labour camp near his. They saw each other only in passing from time to time and would talk whenever they got the chance. The pair met again in Russia when Dimka and a number of other Bulgarian women snuck away from the Russian camp they were in and hid in the Yugoslav men's camp, where Vojislav was being held.

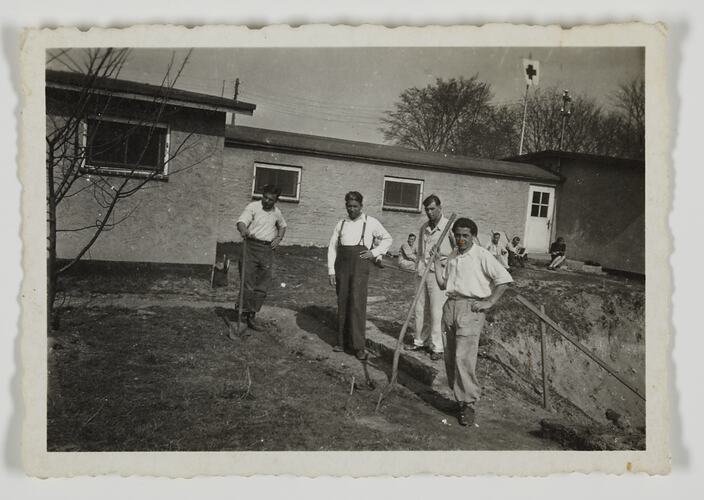

After the war, Vojislav and Dimka were placed as a couple in the same refugee camp in Kassel, West Germany. They got to know each better during this time and married there in 1947. In this camp Vojislav worked as a fireman. During this time the couple traded items given to them by the Red Cross, especially coffee or chocolate, with the local German farmers for meat, eggs, cheese, chickens and pigs, etc. They also ran a still and produced a clear spirit from potatoes and other vegetables obtained from the farmers which they sold to a German pharmacist. He added colour and flavour and sold it on to the American soldiers as cognac.

The war in Yugoslavia wasn't only between the allied and axis forces, the communist Partisans, the royalist Chetniks and the fascist Ustashi also fought each other viciously and terrorised the civilian populations. By 1947 the Partisans were in control. Stories were starting to come back to the camps of Tito's partisans meeting trains of returnees, many of whom were Royalists or Chetniks at the border and killing them and their families.

Vojislav found out from the Red Cross that his first wife had died during the war of an unknown cause. His three teenage children from his first marriage continued to live in his father's house in Vitanovac and Vojislav decided to start a new life somewhere else with Dimka. Over the years Vojislav sent money home to his first family and they remained in contact.

Vojislav and Dimka immigrated to Australia in 1948 aboard the Protea. On arrival to Melbourne they were immediately transferred to Bonegilla Migrant Camp. They were quickly given work with Vojislav working in a brickworks factory in Brunswick and living in Watsonia Barracks and Dimka working as a live in psychiatric nurse's aid at Kew Mental Hospital. They both spoke limited English, but spoke Serbian, Russian, Polish and German.

Between 1951-1954 Vojislav and Dimka lived in an old shop in Brighton with three other couples who they knew from the camps in Germany. In 1952 their daughter Nada was born and about this time Vojislav found work at the Australian National Forge in West Footscray, where he was employed until he retired.

The couple then purchased a house in Whitehall Street in Footscray. Their second daughter, Lily, was born in 1956. Several members of Vojislav's family came out from Yugoslavia to visit Australia, as Tito's government allowed its citizens to leave the country, unlike many other Eastern European regimes. His son from his first marriage, Petar, came to visit with his brother-in-law, Marinko Ignjatovic, in 1964. They had minimal English language skills, and worked in Melbourne for one year. As a gift to their Australian family, they brought over a number of items including a skirt made with traditional designs, hand woven rugs, records, slivovitz and other items. In 2006 when visiting relatives in Belgrade Nada mentioned the skirt, after having had it for over 40 years. She was informed that the skirt was over 100 years old when it was gifted to them by Petar and Marinko.

Vojislav's daughter, Radmila Ignjatovic and his great-granddaughter Ivana (who was around 6 years old at the time) also came to visit and stayed for 6 months. Vojislav returned to Yugoslavia twice to visit his family, by boat in the 1960s and by plane in the 1970s. He died in Melbourne in 1987.