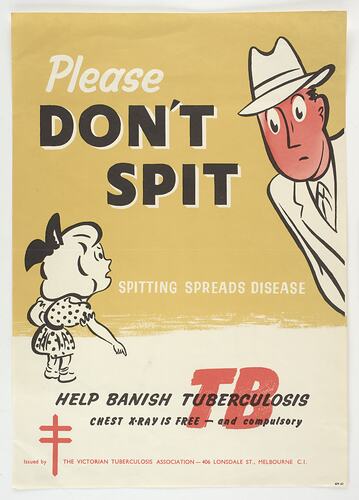

Tuberculosis (TB), also known as consumption or phthisis, has circulated in human populations for millenia, and was responsible for one in four deaths in the 19th century. It is caused by a bacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which most often affects the lungs - hence the type pulmonary tuberculosis - but can also affect other parts of the body, including the blood system, the lymphatic system (the archaic term scrofula refers to tuberculous lymphadenopathy of the neck) and the brain, where it can cause fatal meningitis. It is transmitted through the air via cough, sneeze or spit, and only a few of germs are needed to cause infection. Only about 10% of people with TB infection will develop TB disease, but can transmit it without being symptomatic. Sufferers typically develop a significant cough, spit blood, suffer fever and become debilitated. TB typically has chronic progression and long treatment, but 'galloping consumption', as it was known in the 19th century, could rapidly cause death.

The climate of Australia was thought to be beneficial to sufferers, inducing many to migrate from places such as Great Britain. The arrival of people suffering from tuberculosis exposed local populations to risk, including First Peoples communities, who had no resistance to the bacteria and suffered greatly as a result.

Tuberculosis cases rose in Victoria in the final decades of the 19th century, thought to have been made worse by repeated epidemics of measles, which weakened the immune system. Tuberculosis was much-feared: it could strike any family, suffering might last for years and there was no cure. Some people survived, but the reasons were not understood. Bed rest, treatments in elevated sanatoria where the air was thought to be more healthy and clean, and symptomatic treatments such as sucking fluid from the lungs, were amongst the few options for patients. Amongst posited (but ineffectual) treatments reported in Victorian newspapers were fermented mare's milk (1882); vapor of carbolic acid (1882); pills made of creosote, belladonna extract, opium and rhubarb (1882); and aluminum pills (1884). Advice was for the prevention of tuberculosis was more helpful, including not spitting; not sharing dishes; cleaning toilets used by infected people; sleeping in separate rooms from the sick; and suggesting consumptive mothers avoid close contact with infants (1890).

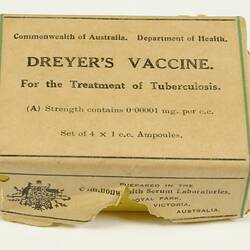

In 1882 German microbiologist Robert Koch identified the Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which paved the way for research into effective treatments and vaccination, but at the start of the 20th century tuberculosis remained the leading cause of death for women in Australia, and the second largest cause of death for men. Then tuberculosis began to significantly decline across the developed world. Improved living conditions, hygiene practices, nutrition and medical care all played a part. The development of the BCG (Bacille Calmette-Guérin) vaccine by French bacteriologists Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin, and used in populations from the 1920s, made a significant impact on the incidence of TB.

During World War II that Ukrainian-American biochemist and microbiologist Selman Waksman identified the first effective anti-tuberculous drug, streptomycin. The use of isoniazid (INH) from 1952 also significantly improved treatment.

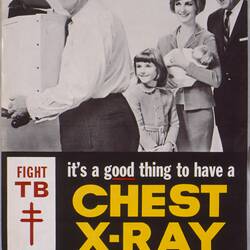

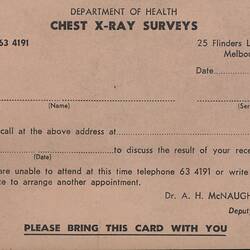

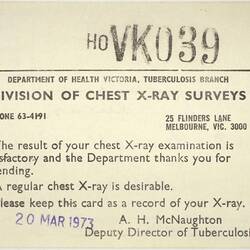

In Australia, a Division of Tuberculosis was established within the Federal Department of Health in 1927, and in 1929 it laid out a plan for the control of TB in Australia. In 1937 the newly-established National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) established a Standing Committee on Tuberculosis, which collated statistics on TB infection rates and began directly funding research into TB. In 1945 a bacteriologist at the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science in Adelaide, Dr Nancy Atkinson, produced the first Australian-made BCG vaccine, later produced in quantity by the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories (CSL). Also in 1945, the Australian Parliament passed the Tuberculosis Act, creating the first comprehensive national health campaign to eradicate TB. Between 1948 and 1976 an Australian Tuberculosis Campaign provided citizens with free diagnostic chest X-rays, medical care and a Tuberculosis Allowance while being treated.

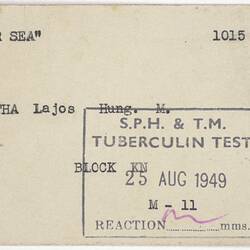

In Victoria, the use of x-rays for tuberculosis diagnosis was introduced in the mid-1940s, with fixed units at Prahran Chest Clinic and other sites including South Melbourne Town Hall, Coburg, Williamstown and Geelong. Mobile x-ray vans were also introduced, which visited large factories, institutions and public spaces. Immigrants were also required to have chest x-rays to detect any incoming cases. As a 1956 Commonwealth Department of Health leaflet explained, 'As a new arrival in Australia, you are required by State law to have an x-ray on your chest within a few weeks of your arrival. This x-ray is necessary even though you have had a chest x-ray overseas. This is part of an Australian campaign against tuberculosis...' (SH 980514).

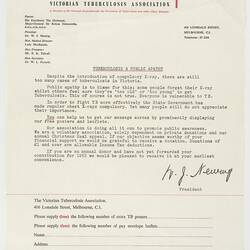

Compulsory x-rays were introduced in 1963 and ceased in 1976, after a prolonged and successful detection campaign, although Marianna Stylianou argues that the success of the tuberculosis campaign was not replicated in Victoria's Indigenous communities - because, for instance, mobile x-rays did not always visit regional communities such as Orbost, community health services were not always adequate, and not all First Peoples were on the electoral roll, which meant they were not identified for inclusion in the TB campaign.

Chest x-rays remain an important tool in the management of tuberculosis, and immigrants to Australia are still required to have them. Tuberculosis is now rarely seen in Victoria.

Tuberculosis is now curable with antimicrobial drugs, although drug-resistant strains have emerged through inappropriate antibiotic use, incorrect prescription, failure to complete prescription courses and poor-quality drugs. Tuberculosis remains the world's leading cause of death through infectious disease, but is preventable through vaccination. The World Health Organization aims to eradicate tuberculosis by 2030.

References

'Tuberculosis', World Health Organisation, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis#:~:text=Tuberculosis%20(TB)%20is%20caused%20by,TB%20germs%20into%20the%20air, accessed 9/6/2020.

S. Luca & T. Mihaescu, 2013. History of BCG Vaccine'. Maedica (Buchar). 2013 Mar; 8(1): 53-58.

'Tuberculosis', NSW Health, https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/factsheets/Pages/tuberculosis.aspx, accessed 9/6/2020.

L. Thomas, 1978. 'The Big C., https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1978/11/09/the-big-c, accessed 9/6/2020.

'History of tuberculosis control in Australia: Case Study', NHMRC, 7 April 2020, https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/impact-case-studies/resources/history-tuberculosis-control-australia.

'Fifty-Fifth Report of the Commission of Public Health', 30 June 1977, Parliament of Victoria.

Janet McCalman, 2005. 'Diseases and Epidemics', Encyclopedia of Melbourne.

1882 'SCIENCE.', Leader (Melbourne, Vic. : 1862 - 1918, 1935), 21 January, p. 3. , viewed 09 Jun 2020, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article198489969.

1884 'Remedy for Phthisis.', The North Eastern Ensign (Benalla, Vic. : 1872 - 1938), 9 September, p. 2. (SUPPLEMENT TO The North Eastern Ensign.), viewed 09 Jun 2020, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article70804730.

1890 'Health.', The Horsham Times (Vic. : 1882 - 1954), 1 August, p. 2. (SUPPLEMENT), viewed 09 Jun 2020, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article72866022.

'A Scandal Which Must be Corrected': Reconsidering the Success of the Australian Tuberculosis Campaign'. Health and History, Vol. 11, No. 2 (2009), pp. 21-41.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Article types