SCIENTIFIC EXPLORATIONS OF BASS STRAITS ISLANDS

INTERESTING TRIP TO THE FURNEAUX GROUP

(By A Special Correspondent)

The Field Naturalist Club of Victoria first commenced a series of scientific expeditions to the islands in Bass Straits during November, 1887, when the Government of the day were good enough to allow the steamer Lady Lock to convey a party of 26 members (with Mr. A.J Campbell as leader to King Island).

King Island is an exceedingly rough and scrubby one, about 40 miles long, by a breadth varying from 10 to 13 miles, and is located in the western entrances of Bass Straits, exactly midway between Cape Otway, Victoria, and the north-west part of Tasmania. The Naturalist spent 18 days on the island, making their headquarters camp near the mouth of the Yellow Rock Rivulet. From this base they travelled in detachments in all about 160 or 170 miles of country, performing much laborious work. It was by no means an ideal picnic outing which some of the stayers at home are inclined to imagine. However, the result was the establishment of the fauna and flora, which was hitherto unknown, of an island lying at our door. Eight species of animals were found, including tow varieties of wallaby. There were over 70 species of birds obtained or identified, besides four kinds of snakes, other reptiles, fish &c, while hundreds of plants were collected and duly classified for the club by the Government botanist, Baron von Mueller. The detailed results of the King Island expedition were published in the Naturalist, the journal of the club, January, 1888.

In 1889 E,D. Atkinson, C. E. (an honorary member of the club(, explored the islands lying between King Island and Tasmania, thus completing the natural history observations of all the islands on the western side of Bass Straits.

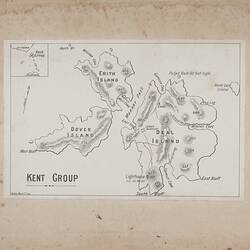

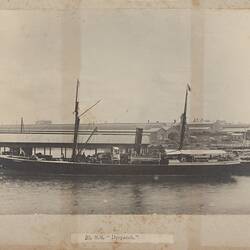

The club then turned its attention to groups of islands on the eastern side of the Straits. In November, 1890, a party of seven members, in charge of Mr. D. Le Souef, was landed by Messers. Huddart, Parker, and Co's steamer despatch on the lovely and romantic islets of Kent Group, situated about fifty miles southward of Wilson's Promontory. This group, which consists of three main and two outlying islands, appears to be peaks of a once mighty chain of mountains, where still evidence of sources of ferntree gullies, and where the giant forms of Gippsland trees now exist as dwarfs not much higher than mallee scrub. On Kent Croup the naturalist made a brief sojourn of 11 days only, but not too short for enthusiasts to establish the natural history of the islands, which produced many novelties, where opossums were found living under tussocks of grass instead of in hollow trees, and where fossil remains were unearthed and subsequently identified by Sir Frederick M'Coy as those in part of the old man kangaroo (Macropus major).

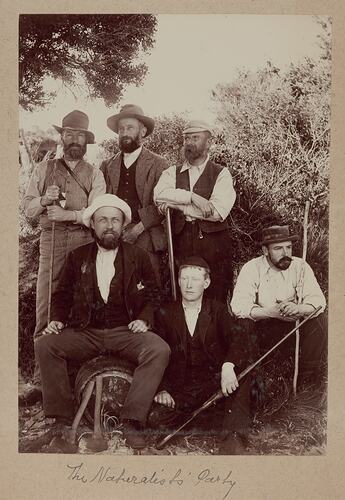

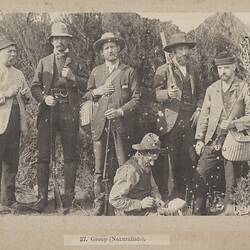

The remaining group of Flinders or Furneaux Islands has just been visited by a small party of ornithologist. As this group is by far the largest in the Straits it was hoped that collections in the various departments of the Field Naturalist Club's work would have joined the expedition, but the late financial depression has had an effect on the amateur naturalist as well as other individuals. Possibly had the government aided in the useful work of the club by placing the steamer Lady Loch, as it did in the first instance, at the club's disposal for a passage to and from the group more members would have been enabled to join. However, satisfactory arrangements were made with the enterprising firm of Messrs Huddart, Parker and Co., which resulted in Captain Alexander Mathieson, of the S.S. Alert. Being instructed to land a party consisting of Messrs. J. Gabriel, T. G. Campbell, H. Ashworth, J. F. Bradly, H. Gundersen, and Master Gundersen on the south end of Flinders, the largest islands of the Furneaux Group.

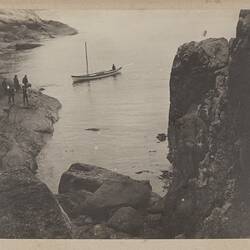

A start is made for Flinders Islands from the South Wharf about half-past 12 o'clock on Saturday, 11th November. After a smart run through the Straits in somewhat rough weather (so we judge by the fiddlers being on the tables, and the productions of 'storm tins'), we arrive at noon the following day off Green Island, 230 miles from Melbourne, and is a small island about five miles from the entrance of Franklin Sound, between Flinders and Cape barren islands. Captain Mathieson had intended to land us about 10 miles up the Sound, but the prevailing 'dirty' weather of mist and rain obliterated all the navigator's land marks, besides it would be extremely uncomfortable for us to visit Green Island we might just as well do so at the beginning of the trip as at the end, so with our cumbersome camp paraphernalia were are transhipped to the fishing boat belonging to Mr. William Carstairs, which he in the kindest manner possible places at our disposal, and promises to take us to our camping place on the morrow.

Green Island, which is about two miles long, is covered by Mrs Robinson. Ere we have reached her garden gate with genuine hospitality and with uplifted hands she exclaims, 'Welcome ! welcome!' and we receive much attention and comfortable 'shake downs' for the night. We glean from Mrs Robinson some useful information in reference to the islands. She has resided upon Green Island for 27 years. During that period she and her people have killed no fewer than 900 snakes, about half that number being despatched during the first three or four years. Now instead of 900 venomous reptiles, 900 sheep graze upon the inlet.

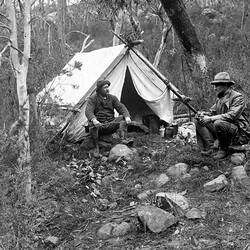

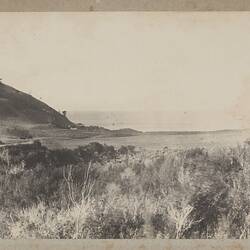

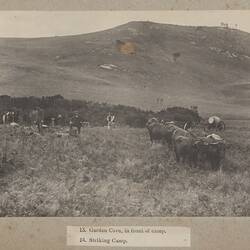

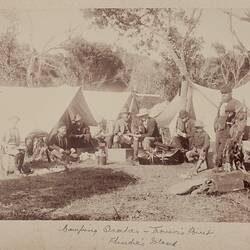

On Monday, 13th we take leave of Mrs Robinson. Mr. Gundersen, with his son proceeding to his selection on Pats River, while the remaining five of the party are conveyed by Mr. Carstairs's boat to the boat harbour near Trouser's Point, at the south- west corner of Flinders, or about three miles from Green Island. Here we find an excellent camping place, high and dry, and well sheltered by scrub. The only drawback existing is the onslaught at times of mosquitoes and sandflies, which would be inevitable nests at any part of the islands. The site of our camp is near the mouth of Forthingate (a corruption, so it is said, of 'Fork and Kid') Creek, but its water like all these streams on the Straits islands are slightly tea-coloured, yet perfectly wholesome. The creek's course is short and merry. Rising among the peaks of Flinders it rushes down a wild, wooded valley over beautiful topazes and other gem stones locally known as 'Killiecrankle diamonds', tumbles down a gorge, and then meanders through a dense scrubby flat to the sea. Having seen to our watering place, the reminder of the day is occupied in erecting tents- one for stories, one for sleeping accommodation, and a third for collecting materials, ammunition, cameras. By evening the westerly weather has abated and the clouds lift, revealing under a slanting sun the native grandeur of the peaks of Flinders, which rise almost from the shores of our bay, and making the outlook from our camp door more sublime than ever we had imagined. Away from the feverish excitement of a busy town life for a brief season we feel exceedingly happy and hope to catch from such scenes of natural beauty more tranquil and lofty ideas.

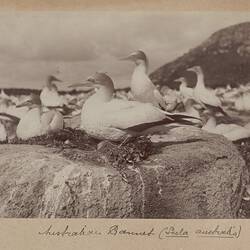

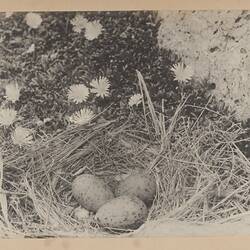

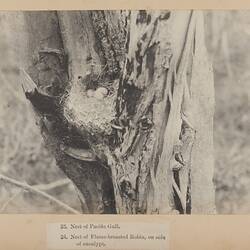

Our first week of course is sent in the neighbourhood of the camp. The scrub- ti-tree (melaleuca), leptospermum, pine, (Callitris), native bazel, &c, interspersed with sheoak (Casuarina, and stunted blue gums- does not yield much. The birds procured or identified are similar to those we had noticed on King Island - that is they pertain to the Tasmanian avifauna, such as the dusky robin, grey tailed thickhead, Selby's shrike-thrush, yellow bellied parakeet, and others. Of the tow first named we obtained nests, the dusky robing being especially beautiful with its set of three apple green eggs. The animals found the island are the same as those of King Island, with the addition of wombats, which the islanders call badgers.

During the moonlit evenings at suitable turns of the tide, we test with small seine net the capabilities of our harbour for fish. The first haul lands mullet of two species, two flatheads of two kinds, besides a few garfish over a foot long, and splendid flounders as large as dinner plates. All are simply delicious when served up in camp, so fresh with a little Lea and Perrin's sauce. Our greatest haul however is one evening when we land, with flipping tails, spluttering the moist sand in all direction, 16 dozen mullet. One breezy day some of the party visit what is locally known as the 'Big' River, which enters the sound five or six miles below our camp. The walk is tedious; the track which lies between the base of the hills and coast is obscured in many places with thick scrubs. Here we notice a ti-tree or melaleuca with soft pace-coloured flowers. The result of the outing is a couple of picturesque photographs, taken near the embouchure.

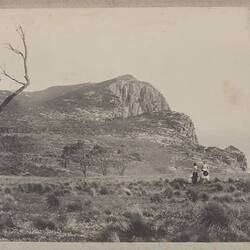

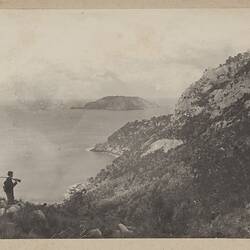

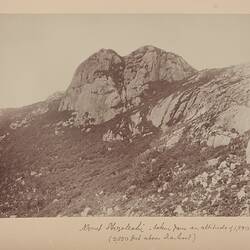

The work near camp is fitly crowned by a successful ascent of Mount Strzelecki, named by or in honour of the explorer and scientist, Count Strzelecki, and which is shown on our maps as the highest of the peaks of Flinders, 2,250 ft above sea level. The oldest islanders of 25 to 30 years standing have never heard of any person, black or white, who had been on the summit before the Field naturalist party. As the crow flies the naked granite peak of Mount Strzelecki is only three miles from our camp, but we could plainly see its rugged and well-nigh unscalable apex would require some considerable negotiation to climb, not to mention the stiff intervening scrub to be threaded. Therefore we first ascend an adjacent and not so lofty a peak and reconnoitre for some future attempts at ancient Strzelecki. Almost immediately on leaving the beach we encounter thick scrub. The standing living scrub is not so objectionable, but at foot the prostrate dead tough scrub is an endless maze of mans traps. However, when we commence to climb in earnest and get amongst the stunted gum trees and over large faces of granite walking is more agreeable. Here in a natural basin of a huge rock is some delightful fresh rain water. We fill the billy in case there is none on the peak whither we are preceding. On we scramble through scrub of various kinds, many in flower, sometimes on hands and knees over slippery stones or under gnarled limbs of trees which hang on curiously with rock encrusted roots. One great face of rock is literally carpeted with velvet pile of moss of the most approved shade of rich aesthetic green. On a perpendicular ledge grows an epiphytal orchid in large patches, illuminated with small delicate yellowish flowers. We had not seen it before, but since Baron von Mueller has reminded us that it is known to botanist as Dendrobium striolatum, is an extra tropical species of mostly tropical genus, and was first collected by Dr. Milligan in the precise locality 50 years ago. In secret hollow that catch the rich alluvial earth which has slipped from its rocky holds above we wander waist high in a perfect garden of large white immortals. At noon we are only as yet 1,000ft above the sea. On the exposed situations we find the wind exceedingly chilly, and seeking the warm lap (for the sun is shining) of a great flat, lichen covered rock, we refresh ourselves with billy tea and a basket lunch. At 1,500ft, after more travelling, or rather struggling upward, still over rocks and through dense scrub, which are bedecked with mosses and lichen, with old ferns peeping out of sheltered nooks, we reach the craggy pinnacle of an unnamed peak. Of course, as may be imagined the outlook is sublime in the extreme, and we are overwhelmed with the wild magnificence of the scene on every side of rocks, hills, wooded valleys, sea and islands. But what fascinates us most is the double headed peak of Strzelecki, which is still towering 1,000ft above us, and separated by scrubby valley yawning 500ft or 600ft below us. From Strzelecki the serrated forms of ten or twelve other peaks cut the skyline like teeth of an immense saw, and trend to the south down to the sea. After photographing the topography of the locality and determining a route for a future attempt of Strzelecki it self, we return down campward. This little jaunt alone occupies seven hours and gives us a very good idea what to expect in encountering the bolder main peak.

To reach this coveted goal the first fine day is selected, when Messrs. Gabriel, Bradly and Ashworth, set out punctually at 7 o'clock. Following the strand for some distance the plucky trio dive into the scrub and tackle at once the foothills of the granite-crowned giant. The first 1,500ft are very much a repetition of what was experienced on the unnamed peak a few days previously. On account of the abrupt nature of the upper portion of the Strzelecki Peak it is found unscalable from the western or sea side, therefore the party is forced round to the northern side, where, fortunately they strike a rocky watercourse fairly embowered with fern, fragrant musk and other trees, from whose stems hang bright poly pods and tassels like yoopods, white numerous fine mosses and lichens, thriving on the moisture of their situation ( for if it is not raining the peak is almost invariably cloud capped) envelope wood and stone alike everywhere in rich profusion. The mountain thrush is observed in these lofty solitudes, which are also enlivened by the presence of the lovely pink breasted robin. Again, fortunately, the watercourse leads up to near the summit, where the party, in a rush for the topmost rock run over a small snake, the only sign of animal life of the very top. Exactly at half past 3pm the three naturalist stand monarchs of all they survey from the western end of the double headed peak of Strzelecki. Deducting half an hour for lunch, the climb took eight hours of continuous toll, not to mention collisions with trees and fall of rocks, but the visions beggar description, are ample compensation for so much physical exertion endured to obtain the glorious scenes.

One phase of the sight is simply a great living geographical lesson on the Furneaux Group of Islands. The coign of vantage of the beholders is approximately the centre of the entire group at an altitude of about 2,550ft (their aneroid only registers 2,430ft, but as an atmospheric disturbance occurred during the ascent, it may in a measure account for the discrepancy.). The whole group which is separated from Tasmania by Banks Straits, 13 miles wide, can be seen extending north- west and south-eat for 60 miles. The group consist of three principal islands, the largest being Flinders of 36 miles in length by an average breadth of 16 miles, Cape Barren and Clarke Islands, together with numerous small islands and islets, fully 50 in all can be counted from the summit of Strzelecki. But the whole scene cannot be grasped at once. Looking away northwards along Flinders sharp granite ranges extend along the west coast to a vanishing point in the form of Mount Killiecrankie in distant blue. The land on the eastern side of the ranges to the sea is low, consisting of the usual thick scrubs, grass tree flats, ti-trees swamps, and poor country generally of a very uninviting description, except, perhaps, for the wallaby hunter.

Then turning eastward, and looking across 80 miles of country, clothed in dark sombre- coloured vegetation, broken with the surface of lagoons, the beholders see Babel Island, and beyond the great main from whence Captain Tobles Furneaux, the discoverer of the group, first looked upon the land in 1773, and then stood away for New Zealand, recording as his opinions "that there is no straits between New Holland and Van Dieman's Land, but a very deep bay'.

Again turning south, the view is even more enchanting. Immediately below lies a dark valley 1,000ft deep choked up with trees, dead and living and scrub brightened now, and then with light coloured patches, showing the tops of flowering shrubs. Then appears Franklin Sound, with quite an archipelago of lovely islets, separating Flinders Island and Cape Barren Island, with its culminating figure of Mount Munro 10 Miles distant, and only 200ft., lower in altitude than Strzelecki. Still further in the distance is seen the loom of the land of Tasmania with intermittent gleams from the streaks of sandy beaches at its base.

Finally, facing west the naturalist fancy they can almost throw a stone upon the white canvas of their tents as they nestle in the scrub on the shore of the bay below, so deceptive is the distance. Beyond are Green and Kangaroo Islands, and still further Hummock Island on the right with the cone shaped Chappell Island, Badger and Goose (with its lighthouse) islands o the other hand. The sightseers have not long to contemplate all the scenes of inexpressible grandeur, but have to tumble down again the mount with is dangerous declivities. As it is the shadows of night overtake them in the scrub, but by good fortune in floundering through a mucky ti-tree swamp they strike the beach, and reach camp in safety shortly before 9 o'clock. Welt did they relish the roasted Cape Barren goose and plum pudding that were prepared for them in camp, and even a bottle of good old wine was not wanting on the occasion.

More Information

-

Keywords

-

Authors

-

Contributors

-

Article types